Foreword

Aotearoa is an archipelago of islands, set in the heart of the world’s largest ocean. According to scientific accounts, its mountains, rivers and coastlines have been co-evolving with local plants and animals for perhaps 80 million years. Some of these species floated, flew or were blown here, surviving a long, dangerous air- or sea-borne journey. In this vast oceanic expanse, small founder populations rapidly adapted to local landscapes, generating an array of unique, sometimes extravagant life forms. As the naturalist Jared Diamond has remarked.

”Examining the New Zealand biota is the closest we will get to the opportunity to study life on another planet.

Read More

Above and below ground, o tatou ngahere, our forests – living communities of thousands of different plants, birds, reptiles, insects, fungi and bacteria, many of them unique to this country – work together in intricate networks of exchange. When the first star navigators arrived from tropical Polynesia in Aotearoa perhaps eight hundred years ago, they found plants and animals, landscapes and seascapes, and climatic conditions radically different from their island homelands. In order to survive, they had to rapidly invent new ways of gardening, fishing, making clothing and tools, and building houses.

Those first settlers acknowledged the pre-human antiquity of the land with chants that described the creation of the cosmos, beginning with a surge of energy followed by thought, memory and desire, knowledge itself; and hau tipu and hau ora, the winds of growth and well-being, blowing life into the cosmos. After aeons of Te Kore (nothingness) and Te Pō (the dark ancestral realm), Ranginui (sky father) and Papa-tūānuku (earth mother) emerge, locked together in a primal embrace with their children, the ancestors of the ocean, winds , root crops, wild foods, forests and people crushed between them. Weary of their confinement, one of these children, Tāne-mahuta, the ancestor of forests, lies on his back and thrusts up with his legs, forcing earth and sky apart to bring light into the world. As his hair roots in the ground, trees spring up, the first tipuna (lit. ‘grown); and as Ranginui weeps for his wife, his tears run across her body, forming the first lakes, rivers and streams, springs and wetlands. All of these life forms – including trees, people, lizards and birds – are linked by whakapapa, a vast kin network on a cosmic scale.

– Photo Credit Jeremy Salmond

The ancestors of Māori brought new animals, plants and technologies from the tropics to Aotearoa, changing the networks of life in these landscapes. They introduced the kiore (Polynesian rat) and kurī (Polynesian dog) which ate birds and lizards; cultivated crops including kumara, taro, hue (gourd) and aute (bark-cloth); and hunted in the forest for kiore, birds and wild foods. These first settlers cleared the bush with fire for fern-root diggings and gardens, and chopped down trees for waka (canoes) and whare (houses) with stone adzes, establishing ancestral use-rights to gardens, birding trees and eeling pools at particular times of the year. In all of these activities, they acknowledged their kinship with other life forms, with karakia (chants) asking the ancestors permission to harvest their children. If they failed to do this, the birds would fly away and the trees would fail to fruit, as hau ora (wind of life) became mate (sickness and death), and the mauri (life force) of the forest would falter.

About two hundred and fifty years ago, when the first Europeans arrived on the shores of Aotearoa, their ships carried a cargo of colliding cosmologies. On the one hand, various ‘Enlightenment’ thinkers in Europe and later, Alexander von Humboldt in Germany and Charles Darwin in England saw the world as a ‘web of life,’ shaped by networks of relations among (and within) different life forms, animated by interactions among complementary forces – a way of thinking that resonates closely with Māori cosmological ideas. In his masterwork Kosmos, for example, Alexander von Humboldt wrote about a ‘wonderful web of organic life’ that was ‘animated by one breath – from pole to pole, one life is poured on rocks, plants, animals, and even into the swelling breast of man’ – a breath that came from the earth itself – a vision that bears an uncanny resemblance to Māori thinking, with its array of complex networks (whakapapa) animated by hau, the breath of life.

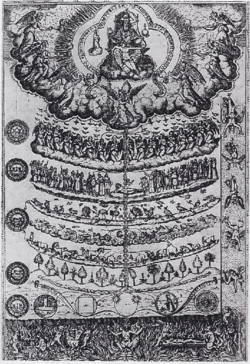

On the other hand, other Western cosmological motifs fundamentally clash with whakapapa. The old mediaeval idea of the Great Chain of Being, for instance, ranks the world from top to bottom in a cosmic hierarchy – with God at the top, followed by the archangels and angels, a divine monarch, the ranks of the aristocracy and commoners (with men over women and children), followed by barbarians and savages, sentient and non-sentient animals, down to plants and rocks. By God-given right, everything on the lower ranks of the Great Chain is expected to offer up tribute and deference to those higher up, a powerful rationale for ideas of Western sovereignty (as well as racism, sexism and slavery), justifying the imperial domination of indigenous peoples as ‘barbarians’ and ‘savages.’ In this way of thinking, Papa-tuanuku lies at the very bottom of the ‘Great Chain of Being,’ along with her plants and animals, offering herself up for human uses – an uneasy origin for ideas such as ‘resource management’ and ‘ecosystem services.’

In Enlightenment science, another powerful framing device was Cartesian dualism, with its’ ‘God’s eye view’ of the wider world. In this way of knowing, Mind was split from Matter, subject from object, culture from nature and people from the environment. In the process, through the quantification of space, time and people and other life forms, reality was transformed by standardised measures into bounded objects at different scales, which could then be counted, classified and commodified. Through cartography and surveying, the earth itself was gridded with lines of latitude and longitude, and at a finer scale, subdivided into blocks that could be bought and sold. These gridded patterns can be seen today on the landscape in town plans, rural sections and fence lines, and in agriculture, horticulture and forestry, with crops planted out in grids on the land.

These ancient ideas still underpin much of our thinking about land use in New Zealand… The first surveyors and land sales, followed by the New Zealand Wars, the land confiscations and the Native Land Court, converted much of the country into ‘blocks’ with lists of ‘owners,’ most of which ended up in the hands of the new settlers. Large areas of indigenous forest were felled and burned as ‘the wilderness’ was ‘tamed,’ a transformation that happened at breakneck pace. When the reaction came, the conservation movement emerged, but the split between Nature and Culture endured. On the one hand, surviving tracts of natural forest were set aside in the ‘conservation estate,’ where they were supposed to remain ‘untouched.’ On the other hand, commercial forests in New Zealand followed classic Cartesian principles – monocultures of exotic conifers planted in grids irrespective of topography, waterways and soil types, and clear-felled at regular intervals. Scientific research in New Zealand has focused overwhelmingly on these industrial plantations, while the lives and possible uses of different types of indigenous forests in Aotearoa remain poorly understood – the gulf between culture and nature, people and environment writ large in our landscapes and lives.

These ancient ideas still underpin much of our thinking about land use in New Zealand… The first surveyors and land sales, followed by the New Zealand Wars, the land confiscations and the Native Land Court, converted much of the country into ‘blocks’ with lists of ‘owners,’ most of which ended up in the hands of the new settlers. Large areas of indigenous forest were felled and burned as ‘the wilderness’ was ‘tamed,’ a transformation that happened at breakneck pace. When the reaction came, the conservation movement emerged, but the split between Nature and Culture endured. On the one hand, surviving tracts of natural forest were set aside in the ‘conservation estate,’ where they were supposed to remain ‘untouched.’ On the other hand, commercial forests in New Zealand followed classic Cartesian principles – monocultures of exotic conifers planted in grids irrespective of topography, waterways and soil types, and clear-felled at regular intervals. Scientific research in New Zealand has focused overwhelmingly on these industrial plantations, while the lives and possible uses of different types of indigenous forests in Aotearoa remain poorly understood – the gulf between culture and nature, people and environment writ large in our landscapes and lives.

In many parts of Europe, in response to climate change with its increased risks of fire and pests such as bark beetles, and widespread biodiversity losses and collapsing ecosystems, nature-based forestry is replacing industrial plantations – in Germany, Switzerland and the Nordic countries, for instance. This kind of commercial forestry echoes Humboldt’s idea of forests as a part of a complex ‘web of life’ that has to be cared for if human beings are to survive. These multi-species, multi-age forests, with species of trees closely adapted to local environments, are harvested in small coups so that the canopy stays intact. Foresters trained in ecology and hydrology rely on regeneration rather than replanting, and take care of waterways, birds and other animals as well as the trees; and the forests are open to the public by law. In Europe, research is increasingly focused on nature-based solutions to ‘wicked problems’ such as climate change; biodiversity losses and ecosystem collapse, including degraded rivers, streams and springs; rising oceans and drowning islands. New Zealand is lagging in all of these areas.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, one of the last significant land masses on earth to be found and settled by people, old fantasies about human domination of the cosmos have had devastating consequences. In very short order, successive generations of settlers have cleared most of our natural forests and locked up the remainder, leaving them in many cases to be ravaged by predators, weeds and browsing mammals. Many of those forests are now dying – for instance, in the Raukūmara Ranges, and elsewhere. We have treated our rivers and streams as rubbish dumps or sewers, stripping their catchments of forest cover, trapping them in stopbanks, burying them underground, choking them with sediment and poisoning them with pollutants, so that relatively few of our waterways are now safe to swim in. We have drained wetlands, filled harbours with mud, and over-fished the ocean. Native species of plants, insects, birds and fish are dying in droves, with at least 4000 species at risk of extinction. And that’s without mentioning climate change, and our idea that the best way to deal with this is to plant even more industrial plantations of exotic conifers. As I have argued, much of this is due to archaic, mythical thinking which puts at risk our chances of thriving, even surviving as a species, and a nation.

So, what to do? In Aotearoa New Zealand, if the speed of devastating ecosystems has been break-neck, it has also been recent. In surviving tracts of bush, the forest floors are still full of seed. As we have discovered at Waikereru, if you take away the predators and weeds, trees and plants with no surviving adults in the forest spring up from the ground, and birds, lizards and insects return at pace. By planting ‘seed islands’ of plants that once grew in the forest, the birds do the rest, wrapping the seeds in bundles of nitrogen and flying them up to steep slopes and gullies. As ferns and trees return, their roots sequester carbon, exchanging nutrients with underground fungal communities while their canopies shade rivers and streams. Life returns to the land, and to rivers and streams. With a bit of help, the web of life is still resilient enough to heal itself in Aotearoa. It’s time to do much more of this kind of work in our beautiful land.

As our campaign ‘O Tātou Ngahere’ suggests, New Zealand’s response to climate change, biodiversity losses and the freshwater crisis provide a brilliant opportunity to springboard these kinds of transformations – in agriculture, horticulture, tourism and forestry, and in urban and rural communities. Our ‘clean green image’ doesn’t have to be a false promise. In Aotearoa, we are still young and smart enough as a nation to change our habits of mind if they put the future at risk. By bringing together ideas of whakapapa with the ‘web of life,’ complexity theory and cutting edge science with our diverse, gorgeous landscapes and seascapes, we can create thriving, profitable farms with fertile soils, home to diverse species and ecosystems – with many farmers already exploring these regenerative strategies. We can have nature-based forests that are alive with birds, with tree species closely adapted to local landscapes, and providing high value, unique timbers and rewarding, long-term jobs. This is a shift that has hardly yet been imagined. Urban forests and streams in suburbs, towns and cities can create healthier, more enjoyable lives and landscapes for locals and high value tourism, based on a ‘clean green’ promise that is not cynical, but authentic and real.

All is not lost.

We can still change the future for our children and grandchildren.

Listen to the cry of Papa-tūānuku, the earth mother:

Piki mai, kake mai Climb here, draw near

Hōmai te waiora ki ahau Bring me the water of life

Kia tutehu ana te moe a te kuia i te pō The sleep of this old woman has been troubled in the night

Ka po, ka ao, ka awatea! But the dawn has come, it is day, it is light!

Nā reira, e āku rangatira, ka nui āku mihi mahana ki a koutou katoa.

– Dame Anne Salmond View Author Bio

Executive Summary

O Tātou Ngahere – Our Forest, is a comprehensive programme of research that details how native forests can be integrated into our whenua for the benefit of all.

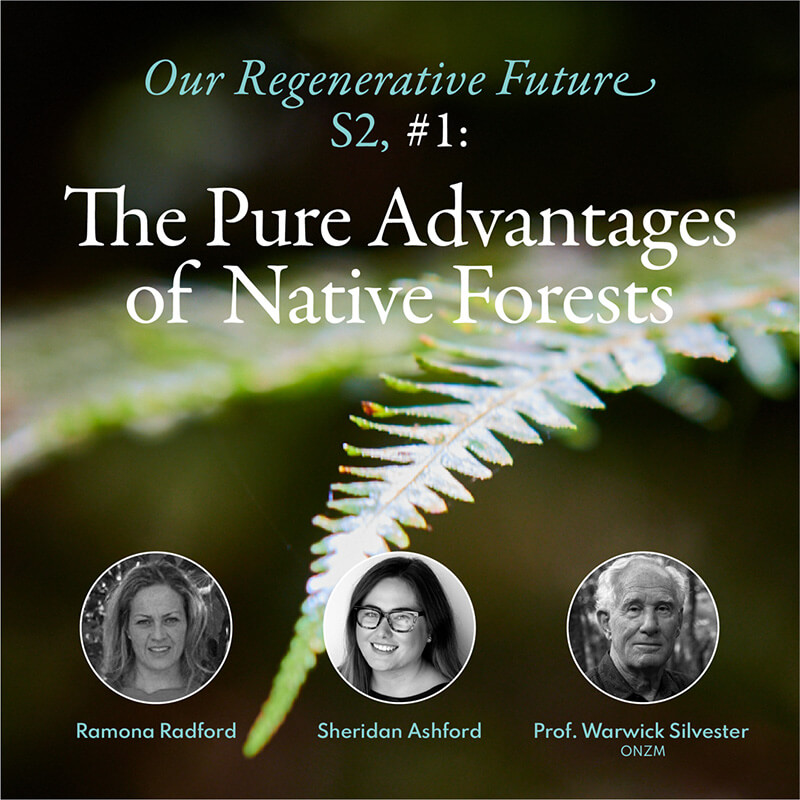

The project is a collaboration between Pure Advantage and the foresters and scientists of Tāne’s Tree Trust, who champion the valuable role our native species can play in the future of forestry in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Our aim is to firmly embed the myriad benefits of native forests into New Zealanders’ thoughts and actions and in the process improve our natural ecosystems and landscapes, contribute to rural economies, and help Aotearoa New Zealand play its part in mitigating climate change.

Together we have convened this suite of essays from some of Aotearoa New Zealand’s foremost thinkers and practitioners in areas related to native forests as the first stage of this campaign. The cumulative knowledge and expertise that underpins these 37 contributions is formidable. We thank all our authors for their input.

The native forests of Aotearoa are unique biological and environmental treasures. They are also cultural taonga, part of our identities as New Zealanders. Their destruction, first by the glacial events of the last two million years, followed by successive waves of human settlers of the past 800 years, has also been extraordinary in terms of the speed and comprehensiveness of habitat and species loss. We are only now becoming fully aware of what this loss means in terms of our own future as a species.

Read More

What also comes through in our contributions, however, is the belief that it is not too late to turn things round.

If the speed of human-led devastation of our ecosystems has been break-neck, it has also been recent, and in most cases there is still a reasonable chance of recovering the many benefits that our natural ecosystems can provide. Our forests are the single most important component of that recovery.

People involved in regenerating and protecting native forests are often surprised at how quickly native species re-appear, and while we know the ever present threats to these re-emerging species, their resilience offers encouragement as we move from thinking, talking and researching to actually taking action on the ground.

Terms like ‘close-to-nature’, ‘near-natural’ and ‘nature-based silviculture’ are not precise. They fit under the umbrella of continuous cover forestry and sustainable forestry, but with explicit emphasis on developing nearer to natural forest structure, processes, and ecology. They also acknowledge the important socio-economic and cultural values that forests can provide – the congruence of this with a Te Ao Māori view is expressed several times in our contributions – encouraging forestry practices that put nature and communities first.

And while there is a preference for indigenous species, these forests can include exotic species or involve managing a transition from exotic plantations to mixed species or native forest compositions. Consequently, they require the development of a range of sophisticated and locally appropriate forest management practices, applied variably, and often at a micro-spatial scale.

Solutions to the challenges we face are beginning to emerge, and many of our authors have constructive suggestions for ways forward: long-term, well-designed policy frameworks; innovative financial instruments; using the pull of commodity markets to drive change; ambitious approaches to biosecurity; and not least, new/old thinking around ways to manage forests following near-to-nature principles. Our foresters must be trained in the holistic skills of managing forests sustainably and in perpetuity for multiple cultural values and uses, and forests must be accessible to all peoples, urban and rural.

Other countries are ahead of Aotearoa in re-defining their approaches to forest management and adopting nearer to nature practices, and we need to learn from those who are further down the track. Working examples of continuous cover forest management systems are few and far between here, but the people pioneering these approaches are passionate about what they are doing, and invariably willing to share their experiences.

O Tātou Ngahere the documentary is one of these stories.

The practical challenges associated with establishing new native forests at scale are also acknowledged, even with the many willing landowners who are prepared to invest their own land, money and time into native forests. Clear strategic thinking will be needed on how to prioritise resource commitments, where the land, labour and trees are going to come from, and how to ensure that, once planted, new forests are maintained. The option of sustainably harvesting some of today’s newly planted forests should also be available to tomorrow’s forest owners and managers.

O Tātou Ngahere is an exciting initiative which aims to engender a mindset shift in our relationship with native forests. We would like to see every farmer and landowner integrate native forests into their best land-use practice. For this to happen, landowners will need encouragement, as well as clear and cogent outcomes that underpin effective policy actions.

Thank you to all those who have contributed to this project. It is our hope that our work and ongoing discussion will inspire and inform Government, business, Iwi and the communities of Aotearoa and help many more Kiwi farmers and forest owners realise that regenerative forestry is a wonderful opportunity for them to embrace.

– Peter Berg & Simon Millar

View Table of Contents

Introduction

Section One: Unlocking the Narrative of Native Forests

Section Two: Near to Nature Forestry

- 2.1 New Old Thinking – Aspiration for Forestry in the Future

- 2.2 Aotearoa’s Moon Shot – the Role of Predator Free in Preserving and Regenerating Native Forests

- 2.3 The State of the Native Plant Nursery Industry in 2021

- 2.4 Nature-based Forestry: Regenerative Models for Aotearoa

- 2.5 The Importance of Native Trees in Agroecosystems

- 2.6 Right Tree, Right Place: Exotic Species Have a Role to Play too

- 2.7 Setting the Record Straight on Carbon Sequestration in Managed Native Forests

- 2.8 Future-proofing our Ngahere

- 2.9 Connecting all Peoples to Urban Forests

- 2.10 Urban Trees and the Auckland Ngahere Strategy

- 2.11 Urban Regeneration: Why Trees are Worth Fighting For

- 2.12 Kia kaha, born-again Ōtautahi forest!

- 2.13 Transitioning Plantations to Native Forest

- 2.14 The Ecology of Transition

- 2.15 Near-to-Nature Forestry in Practice: Case Studies

Section Three – The Forest Economy

- 3.1 Aotearoa New Zealand needs a National Forest Policy

- 3.2 Native Trees and Professional Foresters

- 3.3 The Government’s Forest Industry Transformation Plan

- 3.4 Valuing Native Forests on Private Land

- 3.5 Quantifying Multi-purpose Indigenous Forest Management in New Zealand

- 3.6 Is There a Business Case for Native Forestry?

- 3.7 Catalyzing Investment in Native Forests and World-Class Forestry in Aotearoa New Zealand

Section Four: The Way Forward

- 4.1 Haere taka mua, taka muri. Kaua e whai – Go in Front, Not Behind. Don’t Follow!

- 4.2 Financing Biodiversity

- 4.3 Overcoming the Biosecurity Risks Facing Native Forest

- 4.4 Conservation on Private Land is More Common Than You Think

- 4.5 Ten Golden Rules for Large-scale Establishment of Native Forest

- 4.6 Healing our markets with better facts

- 4.7 Carbon Sequestration by Native Forest – Setting the Record Straight

Credits

Section Links

Unlocking the True Narrative of Native Forests

Near to Nature Forestry

The Forest Economy & Policy

Big Read: Catalyzing Investment in Native Forests and World-Class Forestry in Aotearoa New Zealand

The Way Forward

Trustees; Katherine Corich, Sir Mark Solomon, Sir Stephen Tindall,

Phillip Mills, Rob Morrison, Geoff Ross.

Trustees: Dr. Jacqui Aimers, Peter Berg ONZM, Dr. David Bergin, Ian Brennan, Ian Brown,

Jon Dronfield, Gerard Horgan, Rob McGowan, Paul Quinlan, Prof. Warwick Silvester ONZM.

Office: Mel Ruffell, Amy Spitzer

Presents

O Tātou Ngahere ~ Our Forest

Foreword

Distinguished Professor Dame Anne Salmond

ONZ DBE CBE FNAS CFBA FRSNZ FAHNZ

Contributors

Dr. Mick ABBOTT, Dr. Jacqui AIMERS,Sheridan ASHFORD, Peter BERG ONZM, Dr. David BERGIN, Mark BLOOMBERG, Prof. Bruce BURNS, Annabell CHARTRES, Dan COUP, Howell DAVIES, Mark DEAN, Bill DYCK, Dr. David EVISON, Prof. John FOPPERT, Dr. Adam FORBES, Meg GRAEME, Dr. David HALL, Oliver HENDRICKSON, Denis HOCKING, Gerard HORGAN, Dr. Mark KIMBERLEY, Adrian LOO, Alan MacDONALD, Andrew McEWEN, Robert McGOWAN, Dr. Colin D. MEURK ONZM, Prof. David NORTON, Harriet PALMER, Kevin PRIME, Paul QUINLAN, Abbie REYNOLDS, Prof. Warwick SILVESTER, Dr. Margaret STANLEY, Michael THORNTON-PAY, Prof. Dan TOMPKINS, James TREADWELL, Erana WALKER, Dr. Priscilla WEHI, Nathalie WHITAKER.

Producer

Simon Millar

Communications/Publicity

Creative Director

Warren Elwin

Digital Design & Development

Digital Content Marketing

Vince, Warren, Simon

Editors

Peter Berg, Simon Millar, Harriet Palmer

Editors (contributing)

Dr. David Geraghty, Tāne’s Tree Trust

Filmmakers

As credited