Nature-based forestry is ‘a blend between art, culture, and science’, where forests are managed on a continuous cover basis and allowed to reach their full potential in terms of the holistic services they can provide, including timber. Harnessing the power of markets is suggested as an effective way to bring about a shift in land-use towards more natural models of forest management.

As part of the 2020 Our Regenerative Future campaign, Dame Anne Salmond articulated an aspirational vision for ‘intelligent forestry’ in Aotearoa. She has clearly been inspired by models of continuous cover forestry – specifically, ‘close-to-nature forestry’ practices, where the emphasis is on management of a whole and healthy natural ecosystem and where timber production is only one objective to be managed in a compatible way with the many other cultural, environmental and recreational values in each part of the forest. Generally, this means working with natural regeneration, mixed species, mixed ages, and no clear-felling. The congruence of this with a Te Ao Māori view – and the appropriateness of building on that as a sound basis, to create a new forestry model for Aotearoa, were also made clear. She suggests we use and develop the term ‘nature-based forestry’ for that purpose.

Many of us agree. Indeed, we see scope for such forest management to reflect and regenerate a new and more appropriate relationship between people and nature, land use and kaitiakitanga. Yes, perhaps this is something of an aspirational idyll. But it is important to have inspired goals to strive for.

The amazing thing about forests is their ability to provide such an array of services and values. These include soil, air and water conservation, biodiversity enhancement, carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation, landscape and recreational values, cultural uses, and products – including timber, and employment opportunities. With this capacity, forestry should be the paragon of our primary industries in Aotearoa. But, unfortunately, few of our forests live up to or deliver their multivalent potential.

”Close to nature forestry has increasingly become the accepted forest policy in many places – with some marvellous forests to show for it.

Many cultures have had deep connections to forests and long traditions of using forests for multiple purposes. Modern industrial-scale plantation forestry with its narrow focus on productivity and efficiency has become a matter of debate and dissatisfaction. Communities often expect more from their local forests. Since 1989, the European organisation PRO SILVA has formalised and promoted ‘Close to Nature Forest Management Principles’ as an alternative to clear-felling, and short-term exotic tree plantations. Close to nature forestry has increasingly become the accepted forest policy in many places – with some marvellous forests to show for it.

Terms like ‘close-to-nature’, ‘near-natural’ and ‘nature-based silviculture’ are not precise. They fit under the umbrellas of continuous cover forestry and sustainable forestry, but with explicit emphasis on developing a more natural forest structure, processes, and ecology. However, they also acknowledge the important socio-economic and cultural values that forests can also provide. And while there is a preference for indigenous species, they can include exotic species, or involve managing a transition from exotic monocultures to mixed species or native forest compositions. Consequently, nature-based solutions require the development of a range of sophisticated and locally appropriate forest management practices, applied variably, and often at a micro-spatial scale.

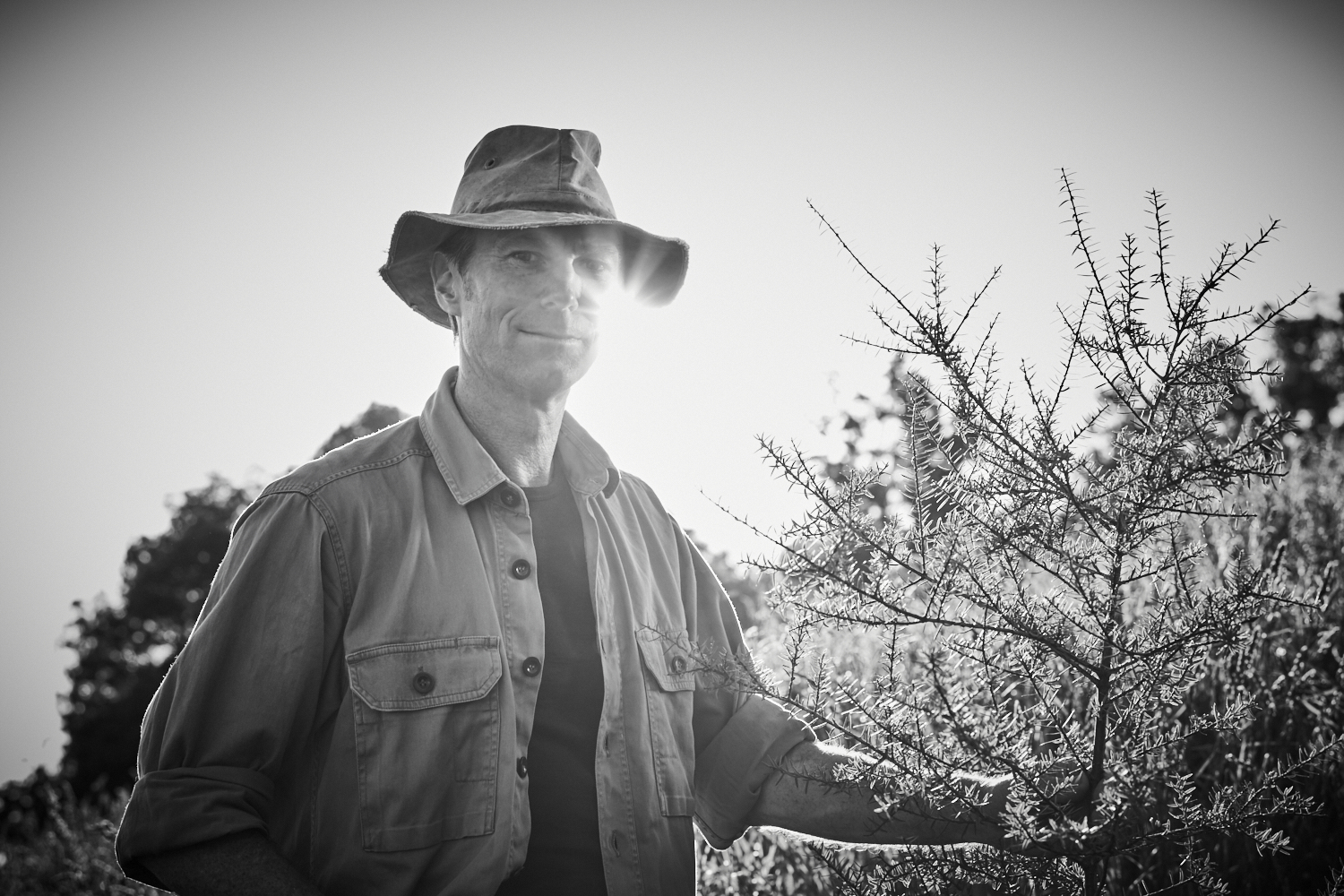

Nature-based forestry is something of a blend between art, culture, and science. Its success relies on care, skill and understanding, and requires an adaptive management approach, one that is informed by and responds to the careful monitoring of the evolving forest. This fosters an interactive relationship with the forest and relies on a stewardship ethic and practice. Of course, it would be romantic to suggest such forest management is easy, more profitable, or perfect. It’s not.

”Nature-based forestry is something of a blend between art, culture, and science

Fortunately, we already have some examples of continuous cover and sustainable indigenous forestry in New Zealand such as John and Rosalie Wardle’s Woodside Forest in Canterbury, and the Tōtara Industry Pilot project in Northland. These case studies show that it is possible to translate such forest management ideas into the context of our own working landscapes and with our own native forest species. Indeed, we see plenty of good reason and scope to do so.

However, it is important to clarify that this is not suggesting harvesting native trees from conservation land. The focus is on private and Māori-owned land in the rural production zone. It is particularly relevant to marginal and reverting hill country farmland, regenerating bush, forestry land, erodible soils and the myriad of steep gullies, riparian margins, escarpments and other difficult to utilise areas that weave through the production landscape. These are often the areas where land use choices have significant implications in terms of environmental impact. And, for many of these areas, a cover of sustainably managed, permanent, native forest, would arguably be the ultimate in terms of environmental and landscape outcomes.

Imagine an extensive web of native forest occupying these sensitive areas, like the connective grouting of a mosaic pattern, cartilage between the bones, a local vegetative matrix within which other land uses are nestled – a filter to our waterways and harbours. In this picture native forest is not a threat or competitor to pastoral farming or plantation forestry, rather a complement, as a healthy diversification and the integration of environmental resilience and improvement.

Bringing about nature-based forestry in Aotearoa

On private land there is a limit to how much land can be given over or retired to conservation. Landowners still need to make a living. Moreover, planting and maintaining native forest is very expensive. Every site is different, so there is no standard cost figure per hectare; establishment costs of around $20,000/ha are not uncommon. Anyone considering planting is well advised to plan and budget carefully and refer to Dr. David Bergin’s Ten Golden Rules for best outcomes. And there are always ongoing costs such as rates and weed and pest control. Utilising and levering-off the processes of natural regeneration will be a key strategy to achieve native afforestation at any significant scale. But whether planting or relying on natural regeneration, most landowners will still need some form of income from their land. Therefore, if we want to see more native forest woven back into our working farms and forests – at anything more than just a token scale – and to see it well-managed, then we need to find ways to incentivise native forest cover as a viable income-producing land use option.

Many human systems influence the economics of land use, and governments have often facilitated the development of industries deemed to be desirable. While regulation can apply certain restraints, technology provides tools for innovation, and innovative policies can push for change, commodity markets are still the biggest drivers and shapers of our rural land use choices, and changes. They are arguably the most creative and can pull new land uses and practices into existence. Markets have fuelled massive transformations of our landscape, from bush to pasture, pasture to pines, pines to dairying, and farms to lifestyle blocks or vineyards. This logic implies if we want more native forest on private land, then harnessing the power of the market could be an effective strategy.

This is the premise that supports using timber and carbon, and potentially payments for ecosystem services, as vehicles to incentivise native forestry as a viable land use option.

Against the background of the climate-change and global biodiversity crisis, nature-based continuous cover forestry – especially with indigenous species- represents a practical and appropriate land use and must be encouraged.

”The attraction of close to nature forestry is its potential to reconcile some production with other values – especially environmentalism.

However, the suggestion of any potential commercial use from native forests on private land, particularly harvesting timber, can meet with strong opposition from some environmentalists. Naturally, they fear it might erode the hard-won gains of the conservation movement. This is a pity, because really, we are on the same side. The attraction of close to nature forestry is its potential to reconcile some production with other values – especially environmentalism.

In contrast, to date New Zealand’s preservationist approach to conservation on private land has generally led to a spatial separation and compartmentalisation of these land uses and values: production here, nature over there. There are limitations and inadequacies, even some perverse outcomes, associated with this approach. Moreover, we need to do far more than just maintain the fragments of nature we have; we need to integrate, connect, and regenerate more nature and resilience within that rural production space too. Nature-based forestry presents one of the most practical opportunities to do so.

”in contrast to the very clumpy cycles of plantation forestry, continuous cover forestry models promise the advantages of diversity and continuity of production and employment and enhanced local landscape values

It is also interesting to see links drawn between such forestry models and local socioeconomic benefits. For example, the Green Party of Ireland promoted Close to Nature Forestry as “a whole new vision for Irish forestry that puts nature and communities first.” Translating that here would hopefully avoid the ramifications associated with single-purpose forestry such as lock-up and leave carbon-farming, walls of wood, slash on beaches and domestic log shortages. Certainly, in contrast to the very clumpy cycles of plantation forestry, continuous cover forestry models promise the advantages of diversity and continuity of production and employment and enhanced local landscape values.

Understanding such consequences of New Zealand’s land use choices is probably what Dame Anne was alluding to with the term ‘intelligent forestry’. Or was it the realisation that we are also able to influence and engineer many of the factors that shape our landscape, such as policy planning, conducive regulatory settings, supportive markets, industry development, and public opinion?

Developing and integrating more regenerative forestry models for Aotearoa is the challenge. Nature can be relied upon to do her part. Are we smart enough to do ours?

Leave a comment