The ETS is proving effective in helping New Zealand reduce its net carbon emissions in the short term, but is stimulating high-risk land-use with a narrow focus. David Hall argues that landowners do have a land ethic, and that new financial and regulatory frameworks are needed to encourage them to adopt interwoven, long-term, and multi-purpose land uses.

Valuing our forests

Imagine that you are the last person on earth. Imagine that everyone else is gone, and that soon you will be too. To pass the time, you take it upon yourself to cut down every tree you can find. Eventually, you arrive upon the last tree on earth. Is it wrong for you, the last person, to cut it down?

This thought experiment from the 1970s helped to crystallise the field of environmental ethics. It was developed by a New Zealand-born philosopher, Richard Routley, who later renamed himself Richard Sylvan.

As you might guess from his chosen surname, Sylvan thought that it was categorically wrong for the last person on Earth to chop down the last tree. He also believed that this conclusion exposed the shortcomings of conventional Western ethics.

Richard Routley was born in 1935 in Levin, New Zealand, but lived much of his adult life in Australia. In his philosophical work, he focused on logic and metaphysics. However, after seeing deforestation in Taranaki as a child, he developed a strong environmental ethic, which he elaborated in the 1970s with his contributions to environmental ethics. Along with his partner Viv Plumwood, another influential environmental philosopher, he also co-wrote a book on forestry policy, The Fight for the Forests (1973), which criticised the clearing of native forest for pine plantations in Australia. When he died in 1996, he had purchased five large tracts of forest for conservation.

Western ethics, he argued, is dominated by the view that people should be free to do whatever they like, as long as they don’t harm other people. However, if you are the last person on Earth, there is no one else to be harmed by your actions. No one to be upset or disadvantaged. Consequently, the last person should be free to pursue any whim, even to exterminate every last tree.

Or at least so says Western ethics.

You don’t need to be a philosopher to share Sylvan’s intuition that this is morally repulsive. Indeed Māori perceived these flaws in Western ethics well before the 1970s. You might have had a similar intuition in recent years, seeing the removal of old urban trees from around Auckland, or the clear-felling of forests from erosion-prone slopes in sensitive catchments, such as Uawa / Tolaga Bay. The value of trees and forests is being depreciated by some decision makers – but not by everyone.

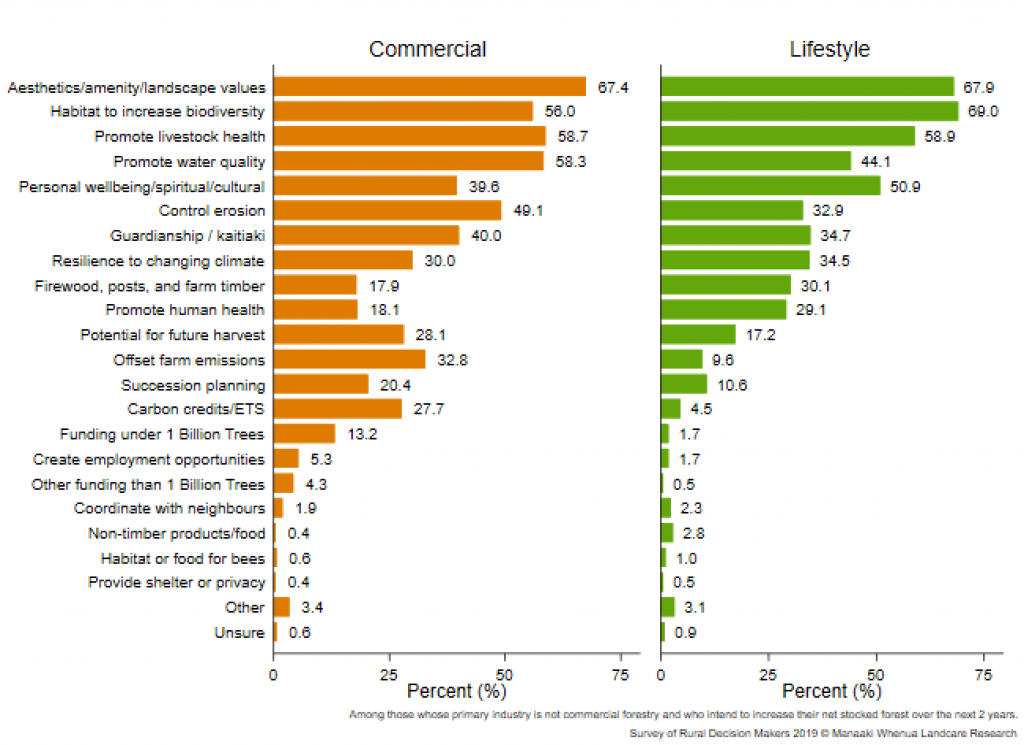

In Manaaki Whenua’s 2019 Survey of Rural Decision Makers, non-foresters were asked for their reasons for planting trees in the near future. Above all else, what motivated landowners was aesthetic value, beauty, the pleasing sight of a flourishing landscape. This was followed by habitat for native biodiversity, water quality, and animal welfare. Then personal wellbeing and kaitiakitanga. And then material benefits like erosion control, land resilience, wood products, and carbon sequestration.

Clearly, a lot of rural New Zealanders already have an environmental ethic, a land ethic. We might empower and enable them further with the right financial and regulatory frameworks – but do we have those frameworks? I would argue not yet.

Let’s narrow in on the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) which, until recently, was commonly framed as New Zealand’s primary policy response to climate change (at the expense of other supplementary policies).

The ETS focuses on just one value: carbon sequestration. By monetising this, the ETS creates a strong incentive for tree species that are fast to grow, and cheap to plant. Typically, that means Pinus radiata.

This remarkable, but controversial tree, is a victim of its own success. In respect to two goods – high-volume supply of softwood timber, and rapid carbon sequestration – Pinus radiata is hard to beat. But as we’ve just seen, these aren’t the only things that rural communities value. They value the things that other tree species, including native tree species, are better able to provide. And these trees, which are often slower growing and more expensive to establish, are disadvantaged by the ETS.

”“letting the ETS do its thing” cannot be sufficient as a national climate strategy

Some people treat this as a failure of the ETS, but it is simply doing what it was designed to do. The objective of the ETS, to be clear, is to create least-cost emissions reductions. It was not designed to do things like improve biodiversity, nor even to create climate resilient landscapes. And this is one reason why “letting the ETS do its thing” cannot be sufficient as a national climate strategy, even if we still need the ETS to put a price on carbon.

To prevent warming of more than 1.5 or 2 degrees, we must radically reduce global carbon dioxide emissions to something close to net zero within the next 30 years. Afforestation can absolutely play a part in this (with the important caveat that it should not be a substitute for earnest, urgent efforts to reduce gross emissions).

But what is also vital is creating a secure supply of negative emissions in the second half of next century, which takes us below zero. All pathways to 1.5C involve removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere; and an important source of these will be nature-based solutions, including forests. A holistic, far-sighted climate strategy will not only value forests that grow quickly, as the ETS already does, but also forests that store carbon securely over the long run.

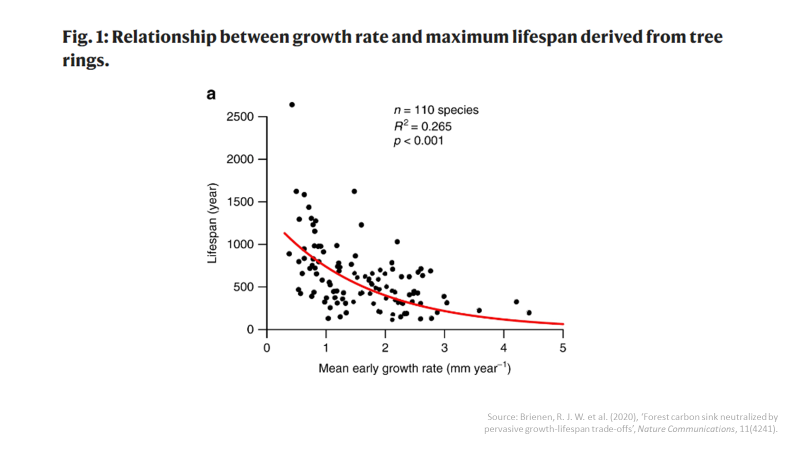

However, I draw your attention to this chart from a recent paper in Nature.

On the y-axis, the lifespan of 110 different tree species, on the x-axistheir growth rate, and then this red line: a negative correlation. In short, the faster the tree grows, the sooner it dies, a near universal phenomenon across almost all species and climates. Live fast die young.

Of course, this doesn’t matter much if we’re harvesting these trees for timber in 25 or 30 years. But if we’re looking for long-term carbon stocks, this ought to give us pause. Carbon farming can be done responsibly, but the door is open to cowboys looking to make a buck by creating least-cost, high-risk, carbon sinks.

And these risks are exacerbated by climate change itself. Under ordinary conditions, forests have natural resilience. But under the extraordinary conditions of a heating world, the risks of pests, wildfire and climate stress multiply. Forest carbon stocks may degrade and diminish as a consequence.

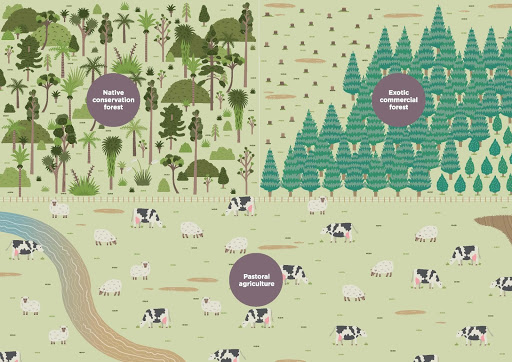

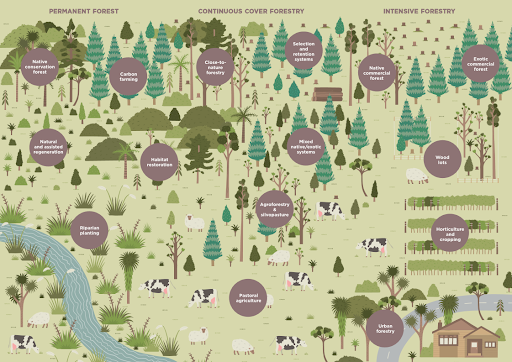

My worry is that New Zealand’s current frameworks are rather prone to creating landscapes that are susceptible to such risks, because they encourage policy and investment decisions that focus on maximising a single value – whether it is financial returns, pure conservation value, or carbon sequestration. They encourage a compartmentalisation of the landscape, and then the intensification of land uses within each compartment, such that the pursuit of one value comes at the expense of others. I call this the Siloed World.

Contrast this with what I call the Interwoven World, or an integrated landscape approach, where diverse forestry and agricultural systems are interwoven through the landscape, to strike a positive balance of environmental, social and economic impacts. On this approach, carbon is being reintegrated into the landscape without entirely displacing other non-forestry land-uses. And the landscape is diversified, in terms of species and management systems, so that our eggs aren’t all in one basket. This is a landscape that’s prepared for future shocks, whether environmental or economic, because it spreads risks, rather than concentrates them.

So if this is the ideal, how do we get there? There are, of course, many levers to pull – but let me champion one: a biodiversity payment, as proposed recently in the Aotearoa Circle report, Resetting the Balance. This could complement the ETS, by valuing and monetising the things that the ETS does not. Crucially, it would help rural decision makers to plant the trees that they genuinely value, which also means that these trees are much more likely to get planted and maintained.

I finish with another philosopher, Amartya Sen, whom our current finance minister is apt to quote because of his work on wellbeing. Sen argues that the way to improve wellbeing is by enhancing human capabilities – that is, our capabilities to live the kinds of lives that we value, and that we have reason to value. The ETS, for all its limitations, does provide landowners with the capabilities to make a living from forests that aren’t being harvested for timber. It provides more than an incentive: it is an enabler, and it can help to create some elements of a flourishing landscape.

”A biodiversity payment would help rural decision makers to plant the trees that they genuinely value, which also means that these trees are much more likely to get planted and maintained.

But other landscape elements need other enablers – through knowledge, culture, skills, infrastructure, regulation, finance, and policy innovation. For our landscapes to reflect what we really value, our systems need to too.

This essay is adapted from a keynote speech given to the Climate Change and Business Conference 2020 (available for viewing here). The speech was dedicated to Dr Ed Hearnshaw (1977–2020).

Leave a comment