Under the banner The systems that got us here have failed, acclaimed business commentator Rod Oram recently shared his insightful stock-take on many things, and lamented,

Too often we can’t even agree a simple set of facts about a problem

so our chances of solving it are minimal.

An intriguing example was last year’s public spat on RNZ between two economics big-hitters: Kate Raworth (of Doughnut Economics fame, self-styled “renegade economist”, and senior researcher at Oxford and Cambridge Universities), and Arthur Grimes (economist, former chair of the Reserve Bank, and professor of wellbeing and public policy at Victoria University of Wellington). While not exactly Greta Thunberg vs Donald Trump, there were similarities: assertive sharp-thinking woman advocating change to arrest environmental catastrophe vs establishment male defending the status quo in a somewhat circuitous and patronising fashion.

At the heart of the spat was an issue Pure Advantage readers may recall Dr. David Rees engaging with two years ago: whether ongoing growth was essential for a flourishing society, and if such growth could possibly be reconciled with solving the climate crisis.

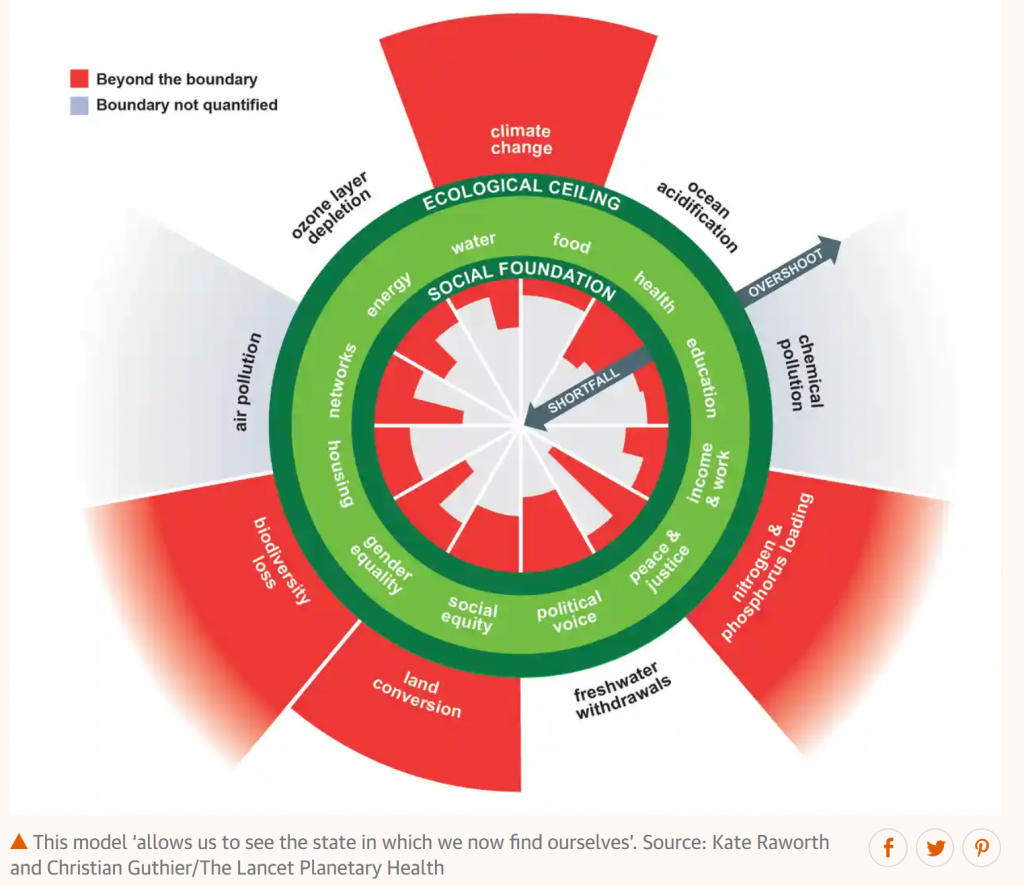

Raworth pressed for replacing our preoccupation with GDP growth with a “21st century natural and social metric”, slammed the narrow market focus of economic education, and emphasised our overstretched planetary boundaries. (Rees aptly termed the green doughnut in the diagram the economic sweet-spot.)

Doughnut Economics diagram showing an acceptable “economic doughnut” (green) balanced between social deprivation (inside) and exceeding planetary boundaries (outside). Source: The Guardian

Grimes portrayed Raworth’s arguments as a “straw man” that added nothing to established knowledge, commented that New Zealand had already pulled back from a GDP fixation, and also expressed concern for the state of the environment.

And Raworth said… And Grimes said…

In fairness, Grimes denied being an advocate of ongoing growth, instead championing raising standards of living. He saw this being driven by innovation (“a fantastic thing”), which he portrayed as leading inevitably to economic growth. The resulting impression was advocating growth by stealth, an impression reinforced when he seemed to call his own bluff, bluntly stating “Another word for improving living standards is growth”.

In a July 2019 RNZ interview , Grimes had commented “New ideas are very dangerous to an established elite”, and it’s hard to escape the sense that, in the way he sought to rebuff Raworth, Grimes was illustrating that very point: an elite professional trying to deflect an innovative challenge to a doctrine he embraces. It seems innovation is a fantastic thing, except the kind Raworth proposes.

In fact, I agree with Grimes about the immense value of innovation, but in 2020 that must mean harnessing creativity to tackle the wicked climate crisis we’re engendering, not escalating Western-type lifestyles that continue to be such a big part of the problem.

The seemingly self-evident notion that increasing income always leads to better quality of life has its serious challengers, as does the premise underpinning many Western economies, that increased consumption is the primary route to human wellbeing.

One of those challengers is Tim Jackson, whose book Prosperity without growth weighs an array of issues in measured fashion. Economist Jackson is no lightweight, either: professor of sustainable development at the University of Surrey, and former Economics Commissioner on the UK Sustainable Development Commission. Among many pertinent observations, Jackson notes,

In the UK the percentage reporting themselves ‘very happy’ declined

from 52% in 1957 to 36% today, even though real incomes have more than doubled.

He also cites a study of the city of Sheffield over a 30- year period, when real incomes doubled but “even the weakest communities in 1971 were stronger than any community now.” We get further insights into the relationship between income and happiness from an analysis across a huge array of countries (see chart).

Source: “Prosperity without growth” by Tim Jackson.

Although clearly implying a dramatic increase in happiness with increased income for low income societies, Jackson notes “after an income level of about $15,000 per capita [1995 $US base], the life-satisfaction score barely responds at all, even to quite large increases in GDP.”

Comparing NZ and the US (circled) reinforces this, with almost identical “happiness” scores in spite of significant differences in GDP per capita.

There is, of course, room for debate around the semantics of “happiness”, “wellbeing”, “prosperity” and the like. Jackson traverses much of that ground, with the broad conclusion that increasing income is of major importance until life’s essentials are met, and thereafter is mainly about “keeping up with the Joneses”. He notes it’s often our conditioning to a perception of shame amongst our peers that propels us to buy things we don’t otherwise need, regardless of our wealth.

Given that every action or product has implications for emissions or resource depletion, this is food for serious thought in an era when we are desperate to minimise such calamitous effects.

Jackson builds on this with insightful comments on that superficial half-brother of innovation, novelty. He cautions that our consumption habits are in part fuelled by social conditioning to attract us to novelty through bestowing it with questionable social symbolism (tied to the above sense of shame), which brings to mind Indian/Canadian poet Rupi Kaur’s incisive poem on fashion:

“A trillion dollar industry that would collapse

if only we believed we were beautiful in the first place”.

In other chapters, Jackson explores green economic strategies like decoupling (achieving growth without increasing environmental impacts), and highlights the distinction between relative decoupling (fewer emissions per unit) and the critical goal of absolute decoupling (where growth occurs without raising total emissions).

For absolute decoupling, Jackson gives a rule of thumb: the rate of relative decoupling must exceed population growth plus income growth combined. This is an outcome that has eluded almost every economy, and defied almost every aspirational policy.

In the prologue to his book’s second edition, Jackson reflects on 6 more years of research in this area:

Green growth is not going to be easier than I had suggested

– it’s going to be harder than anyone had ever thought.

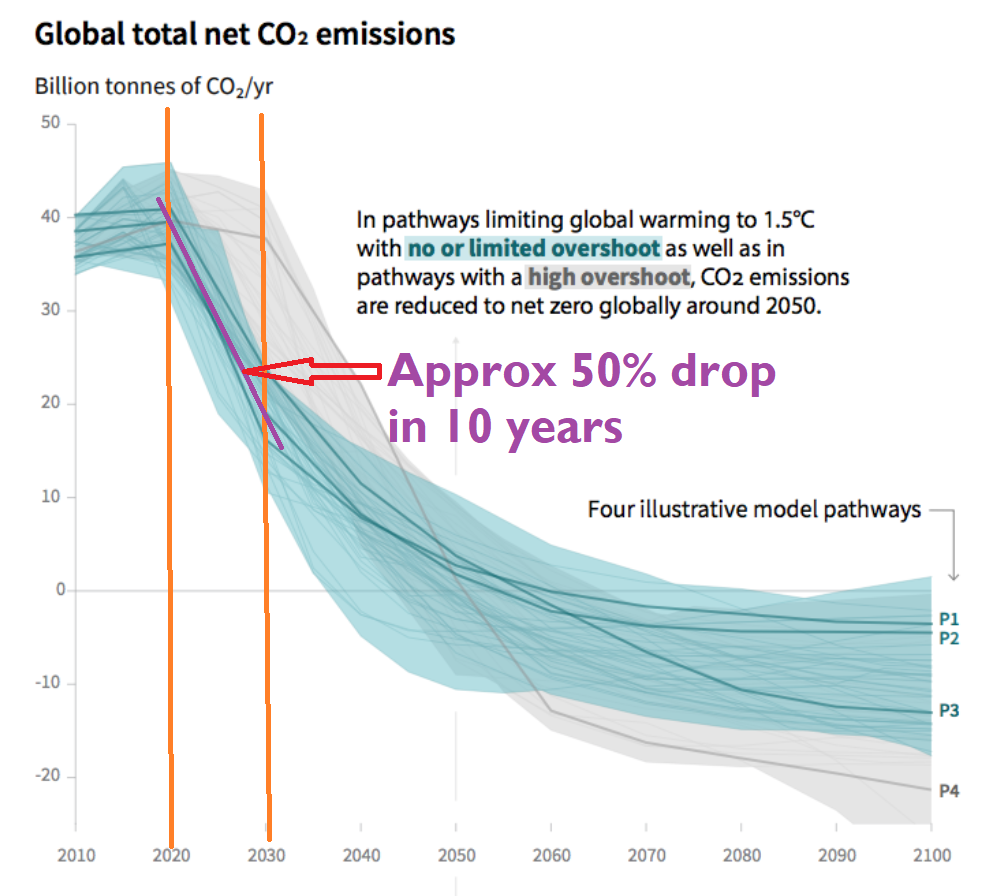

Framed in the stepping stones context of our Zero Carbon Act, and challenged with descending the 2018 IPCC CO2 emissions reduction curve (see diagram), this would mean effort that Jackson describes as “at best heroic”: a spectacular, improbable and prolonged 12% annual relative decoupling, while holding combined population and income growth below 5%. (Keep combined growth down to say 2% and we still need relative decoupling around a daunting 9% p.a.).

Dropping 50% in 10 years is about 6.8% p.a.; World Bank shows NZ population growing 2.1% in 2017, and GDP 3.0%. On that basis we need 11.9% p.a. decoupling for an absolute drop of 50% in 10 years. Chart IPCC 2018, annotation Lindsay Wood.

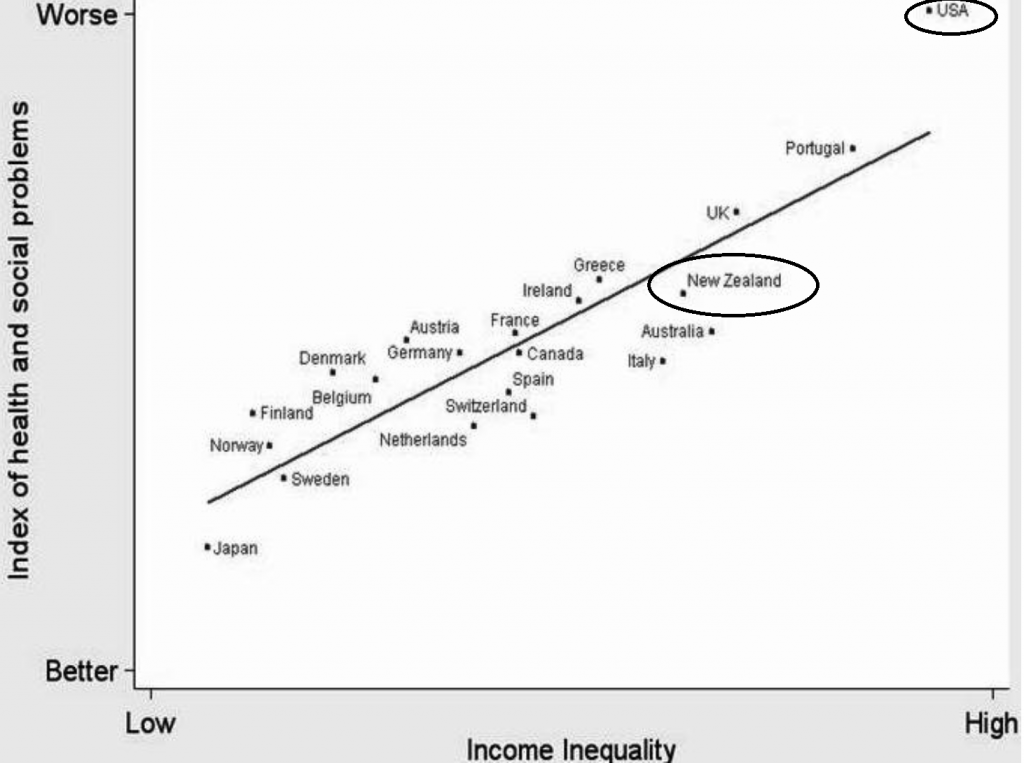

Another eye-opening reference to this discussion is The Spirit Level, written in 2010 by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett (also professors – in sociology and epidemiology). One of its several surprises sits right in its subtitle: “More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better”.

The authors’ exploration of numerous connections between income inequality and different social criteria strongly supports the subtitle’s claim, shows how inequality commonly disadvantages the well-off too, and raises serious doubts about the social trajectories of free-market economies like New Zealand and the United States.

Like Doughnut Economics and other schools of thought that challenge perceived wisdom, The Spirit Level quickly came under fire, especially regarding statistics. However, in an effort that might warm Rod Oram’s heart, reviewer Hugh Noble wrote The Spirit Level Revisited, a 43-page analysis of the Spirit Level, its statistics, and its key criticisms. While he doesn’t give the book a completely clean bill of health, Noble concludes “The Spirit Level remains standing in the face of this criticism and stands largely unscathed.”

The fresh approach of Doughnut Economics, at a time when we need fresh as never before, has been widely acclaimed, all the way from George Monbiot in the Guardian to Forbes voting it the 2017 book of the year. I’d back the book to join the ranks of the vindicated, alongside The Spirit Level, and that seminal 1972 work from a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called Limits to Growth.

More importantly, it seems folly not to review our habitual focus on income growth, when it might add little to our society’s well being, and also exacerbate the same environmental damage we’re striving to mitigate. Such a review should extend to the place of income inequality, and its relationship with the happiness of all sectors of our society. Rees framed this important issue as “our ability to thrive and prosper regardless of the level of GDP growth.”

I, for one, rate Kate Raworth’s drive to build economics education around social and natural metrics rather than around growth. Is it too much to hope that Arthur Grimes sees the compelling global opportunity in this, and uses his passion for innovation to find creative ways of promoting such a transition at Victoria University of Wellington?

Joining the dots between Raworth, Grimes, and the Pure Advantage mission.

As a generator and communicator of knowledge around green growth Pure Advantage’s what we do page inspires us with visionary aims to,

Dispel any lingering misconceptions around wealth creation and environmental protection being contradictory goals,

and adopt

transformative economic strategies based on green growth

so that

the people and businesses of New Zealand will realize a healthier, wealthier future that is more sustainable in every sense.”

To the extent that Pure Advantage aligns itself with the Green Growth; opportunities for New Zealand, report that it commissioned from the University of Auckland and Vivid Economics, the entity falls more in the Grimes camp, with a preeminent focus on growth, albeit green.

The paper’s Section 3.2 is a sort of Green Economics 101.

Standard economics, we find, is to “protect and enhance the wellbeing of people” (Grimes and Raworth would surely agree!), then “Wellbeing is the result of consumption of many goods, some bought in markets.” (Wow! From the same economic-speak book as Grimes’ “Another word for improving living standards is growth”?)

So, the aim of standard economics is human wellbeing, and the key is getting people to consume stuff.

The Green Growth report distinguishes between market goods and non-market ones. The latter includes “environmental goods”, as the basis for defining green growth, which I paraphrase as:

Green growth is rising output of environmental goods.

The Green Growth report also notes no suitable substitutes exist for some types of environmental capital, such as a liveable climate, and so these must be maintained over time

Am I missing something big?

Isn’t there more to human fulfillment than expanding consumption?

More to our amazing environment than being “capital”, “goods” and “resources”?

Surely our wonderful planet can’t be reduced just to stuff we can make things from and people who consume those things (plus selected environmental features that we should look after, but don’t).

These issues don’t belong right at Pure Advantage’s feet, as Pure Advantage is largely acting as a conduit for applying conventional economic wisdom to environmental causes. It is also actively encouraging new ideas, and has validated its stance by serious third-party investigation (from which I’ve selected just a few salient phrases).

However, it does seem time to re-examine some premises underpinning green growth, and that is the motivation for these two Rethinking Green Growth articles. (Jackson is more blunt! In assessing our approach to poverty, climate and biodiversity, he notes “…simple arithmetic reveals stark choices… are we so blinded by economic growth that we daren’t do the sums for fear of revealing the truth?”)

Jackson aside, for starters here are a few areas I would like to foster discussion around;

- What are robust 21st century concepts of “standard of living” and “wellbeing”, and are they purely functions of “growth” and “consumption”?

- Why are we fixated on increasing incomes and wealth when there’s robust evidence a) that, at NZ’s economic level, greater per capita income does not bring greater wellbeing (but does generate more environmental harm), and b) a consequence may be greater inequality, which makes most of society worse off (and we’re already near the wrong end of the inequality scale)?

- How do we align green growth with a seriously circular economy? Charting the way to a future that is more sustainable in every sense quickly identifies the need for a circular economy (not our current extract-consume-discard linear model) yet the Pure Advantage paper did not pick up on this increasingly-mainstream concept.

- Does economics terminology (natural “goods”, “capital”, “resources” etc.) provide a wise foundation for major strategies that impact heavily on the environment?

Income inequality and societal health. From “The Spirit Level”, 2010.

Hopefully, not only will Victoria University of Wellington revisit its approach to teaching economics, but Pure Advantage will revisit its own philosophy – in further fulfilment of its aspiration to transform how New Zealanders understand and manage the relationship between the environment and the economy.

Fingers crossed!

Read Rethinking Growth Part Two here >

Leave a comment