Anyone who believes in indefinite growth on a physically finite planet is either mad, or an economist – Kenneth Boulding

If you’ve read the NZ Productivity Commission’s milestone 2018 report Low-emissions economy, you’ll know it’s a widely-researched 600-page response to various climate imperatives.

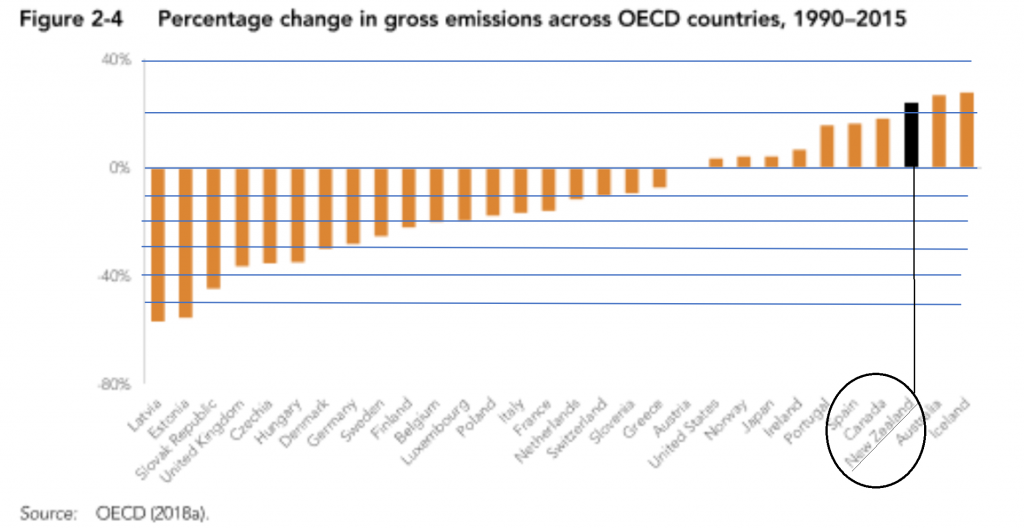

Repeatedly, it flags population and economic growth as causes of rising greenhouse gas emissions, and as overpowering efforts to reduce emissions. For example, between 1990 and 2015, in spite of reducing per-unit relative emissions (e.g. for dairy, vehicles and electricity), New Zealand’s absolute (total) emissions grew 25% (third worst in the OECD, contrasting with a 15% average drop across OECD countries).

Like Arthur Grimes view (see Rethinking Growth Part One), the report also champions innovation, dedicating an entire chapter to it, and calling it “the closest thing to a silver bullet to enable humanity to meet the challenge of avoiding damaging climate change”.

In signalling the centrality of growth to escalating emissions, and of innovation in reducing them, we might expect the commission itself to think outside the square on growth, but it doesn’t.

Either that seems too sacrilegious, or the report is shackled by its own terms of reference:

…consider the different pathways along which

the New Zealand economy could grow and develop…

and

Identify options for how New Zealand could reduce its domestic GHG

through a transition to a lower emissions future,

while at the same time continuing to grow incomes and wellbeing…

Once again, innovation is promoted as fantastic, but not in regard to growth.

And, again, we find the questionable bracketing of “grow incomes and wellbeing”, and yet only fleeting mention of inequality, with no discussion that reducing inequality holds more promise at all levels of our society than increasing incomes. This is especially important when increasing incomes generally exacerbates both emissions and inequality, thus propelling both the environment and society and in wrong directions.

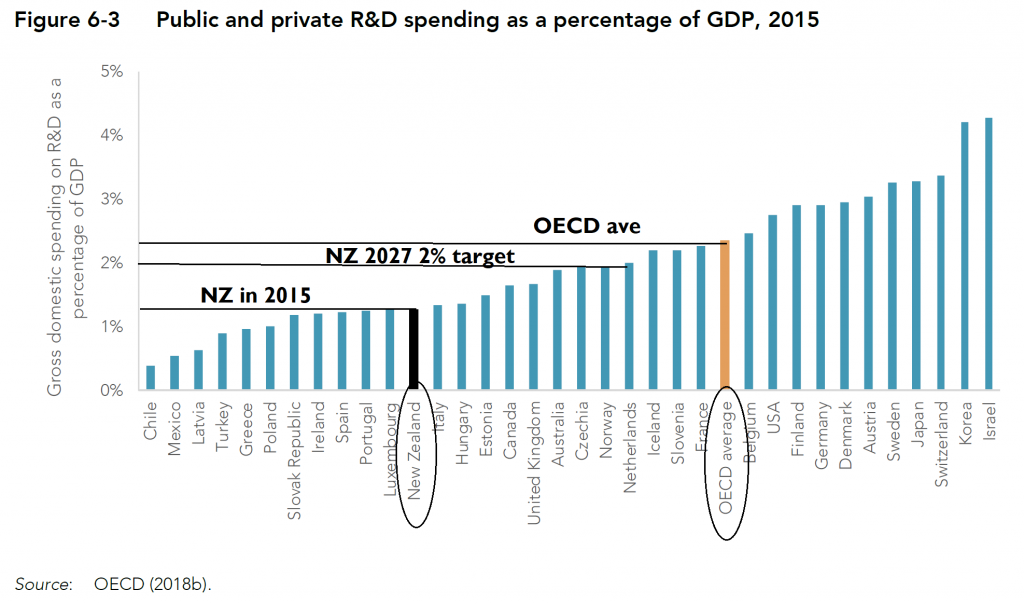

The report does, however, highlight New Zealand’s weak R&D, especially in business, and emphasises the massive business potential for innovation for sustainability. It recommends boosting R&D from a feeble 1.2% of GDP to 2%, (still-lame at well below the OECD 2.3% average). In adopting this unchallenged, the government joined the commission in falling short on both ambition and innovation.

This leaves plenty of space for businesses to do better on both counts. Happily, more groups are being proactive, from the Climate Leaders Coalition, to the Chia Sisters Thousand Business carbon assessment (an initiative in association with the Sustainable Business Network and Carbon offsetter Ekos). But it’s a long, tricky road and we must travel at speed, while negotiating the potholes of patch-protection, uncertainty, and growth focus.

It’s a shame the Government and Productivity Commission weren’t eavesdropping on a discussion at the last Cradle to Cradle Congress (C2C) in Germany. when I was talking with C2C founder Professor Michael Braungart and his colleague and circular economy specialist Doug Mulhall. Doug fixed me with a piercing look. “New Zealand is the perfect place for a world first,” he enthused. “The first complete country to commit to a circular economy.”

Now that’s innovative and ambitious.

“No problem!” I answered. “I’ll fix that.” And pigs might fly!

But maybe Mulhall is right, maybe we should accept the national challenge of being the first to fly that way. The world desperately needs to navigate away from dependence on damaging growth and consumption, and towards a business-friendly economy that truly sustains our environment and our wellbeing.

Pure Advantage is part of this quest and, hopefully, will review where growth sits in their pursuit of environmental goals. Conversely, if growth is pursued, how can it be reconciled with Pure Advantage’s high aspiration of New Zealand being “more sustainable in every sense”.

Such aspiration points strongly towards a circular economy, and demands we extract from nature no faster than she regenerates, and dispose of to nature no faster than she can assimilate, “natural metrics” that align with such planetary boundaries as those espoused in Doughnut Economics.

The Green Growth Opportunities for New Zealand report funded and produced by Pure Advantage researched and written by the The Auckland University and Vivid Economics is a paper that dips a toe into the same pond, with the other foot planted firmly in the “growth” ocean:

A good quality growth metric has to take into account capital

and contributions to wellbeing that are not traded in markets.

Fully natural metrics lead to a significant refocusing

- of our inorganic material chain from extractive processes to widespread recovery and reuse, and

- of organic materials being used only at renewable rates, and then reused or properly returned to nature.

There is now plenty of information on circular economies. Consider SBN founder Rachel Brown’s 2018 commentary The opportunity investment by going circular. In sync with the Productivity Commission, Brown described local circular economies with enormous business potential – think NZ$8.8 billion additional GDP in Auckland by 2030.

WHAT IS A CIRCULAR ECONOMY?

“Looking beyond the current take-make-waste extractive industrial model, a circular economy aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits…decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources… Underpinned by a transition to renewable energy, the circular model builds economic, natural, and social capital. It is based on three principles:

- Design out waste and pollution

- Keep products and materials in use

- Regenerate natural systems”

“Regeneration” (of society as well as nature) is important. “Not making things worse” is insufficient when planetary limits are so overtaxed (see 5 minutes into Kate Raworth’s easy talk here).

“Imagine a building like a tree,” C2C founder Michael Braungart suggests. “A building that cleans water and the air, makes oxygen, generates soil and nutrients.”

Numerous graphics express the circular concept, all entailing serious disengagement from extraction and waste generation. The one below, reinforces reuse and the ongoing value chain, and avoids reference to “recycling”, which is increasingly described as “waste in drag”.

Info on circular economies is widely available. E.g. a lot at Kate Raworth; the NZ Ministry for the Environment; or, for more product orientation, visit C2C Certified.

While this fits the Pure Advantage prescribed definition of green growth (rising output of environmental goods), caution is needed framing this as overall growth when it is largely substitution of, not addition to, economic activity (refer Rethinking Growth Part One).

So, is New Zealand up for a national circular economy?

EXAMPLE: BUILDING SUSTAINABLY IN A CIRCULAR ECONOMY

Globally, we’re building a New York City every month, concrete alone produces up to 10% of all human GHG emissions, and sand is so over-consumed in several countries there are now black markets in it.We have hugely energy-inefficient patterns of subdivision and construction, and build (with the US and Aussie), the world’s largest houses. And the Christchurch earthquake showed how ill-suited our systems are to recovering products, even from new houses.

Although there is a long way to go, there are great initiatives around. E.g. “BAMB” (Buildings as Materials Banks) is a simple conceptual shift with massive implications: once we think of buildings as holding places for materials (not end destinations), the game changes, in design (e.g. standardised components); detailing (simplifying dismantling); construction (different techniques and materials); upstream and downstream value chains; and regulatory compliance. But these are completely doable, and do present marvelous business and sustainability opportunities.

A real join-the-dots opportunity is rushing over our horizon, and NZ is poised for a world-leading response. Our 1990s ETS forests are at milling age (“the wall of wood”). We should store the timber with its precious sequestered carbon, and NZ is a leader in heavy timber construction, with huge multi-faceted benefits:

- Replaces emissions-villains concrete and steel on a big scale.

- Based on renewable resources not extracted ones.

- Better suited to dismantling and reuse.

- Stores sequestered carbon beyond the life of the building.

- Better for the local economy than just exporting logs.

That’s no small ask for a species that, for 12,000 years, has plundered and exhausted one regional environment after another, to the point Yuval Noah Harari, in his seminal book Sapiens, terms us ‘ecological serial killers’. Harari doesn’t finish there, though. He makes the case that prehistoric hunter-gatherers likely had more free time, and more fulfilling lives, than at any time since the agricultural revolution. Let’s factor that into our model of life, and see what we end up with!

Which brings us to energy, with the potential to stand our lifestyle on its head regardless, but more rapidly with climate impacts.

We think of economies as monetary processes, with energy on-demand to help economies do their thing. But there’s compelling evidence, such as from visionary power engineer Professor Pat Bodger (now retired from the University of Canterbury), that it’s the other way round: we run energy economies, with economic activity and lifestyle as functions of the abundance and accessibility of energy Researching this back in the 1980s, Bodger showed that economic activity actually trailed energy availability rather than drove it.

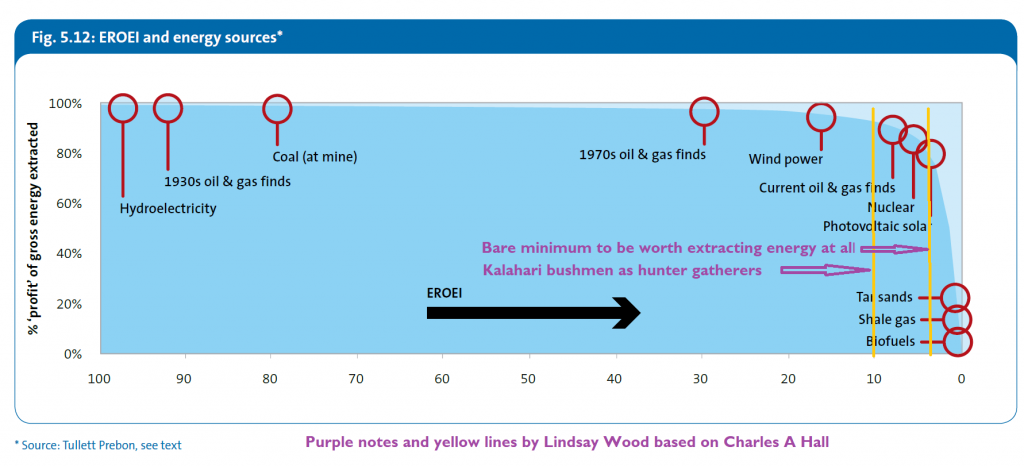

Joseph Tainter, US historian, agrees, writing “Diminishing returns of the Energy Returned on Energy Invested (EROEI) is a chief cause of the collapse of complex societies.”

“The Killer Equation”, ECoE and EROEI

We really run an energy economy

“Diminishing returns of the EROEI is a chief cause of the collapse of complex societies”

Joseph Tainter, American historian

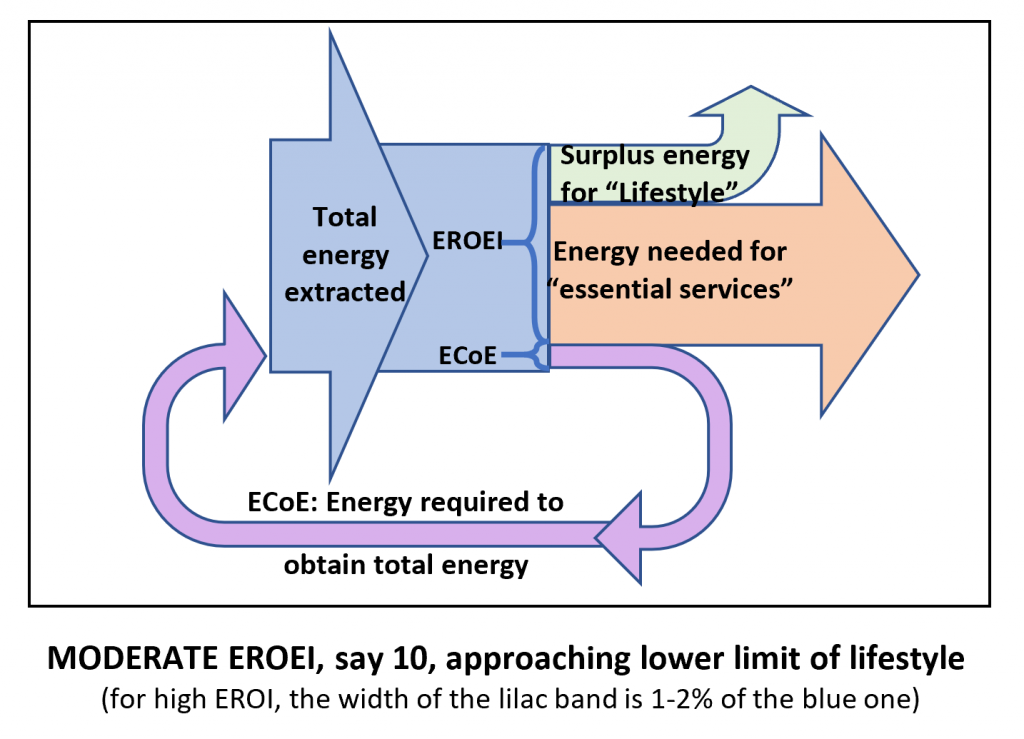

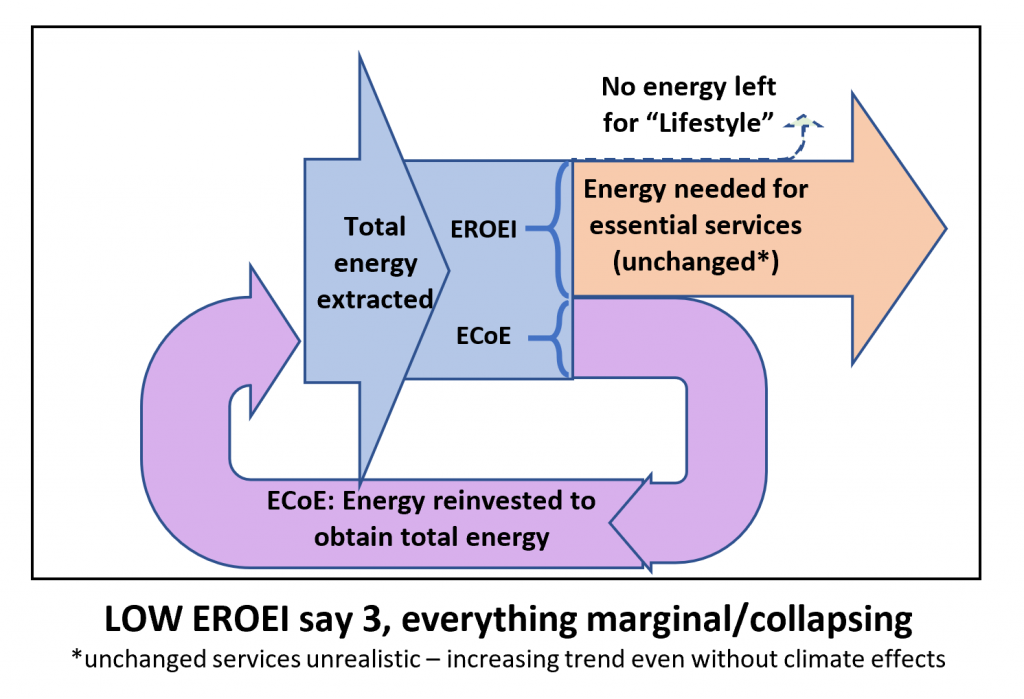

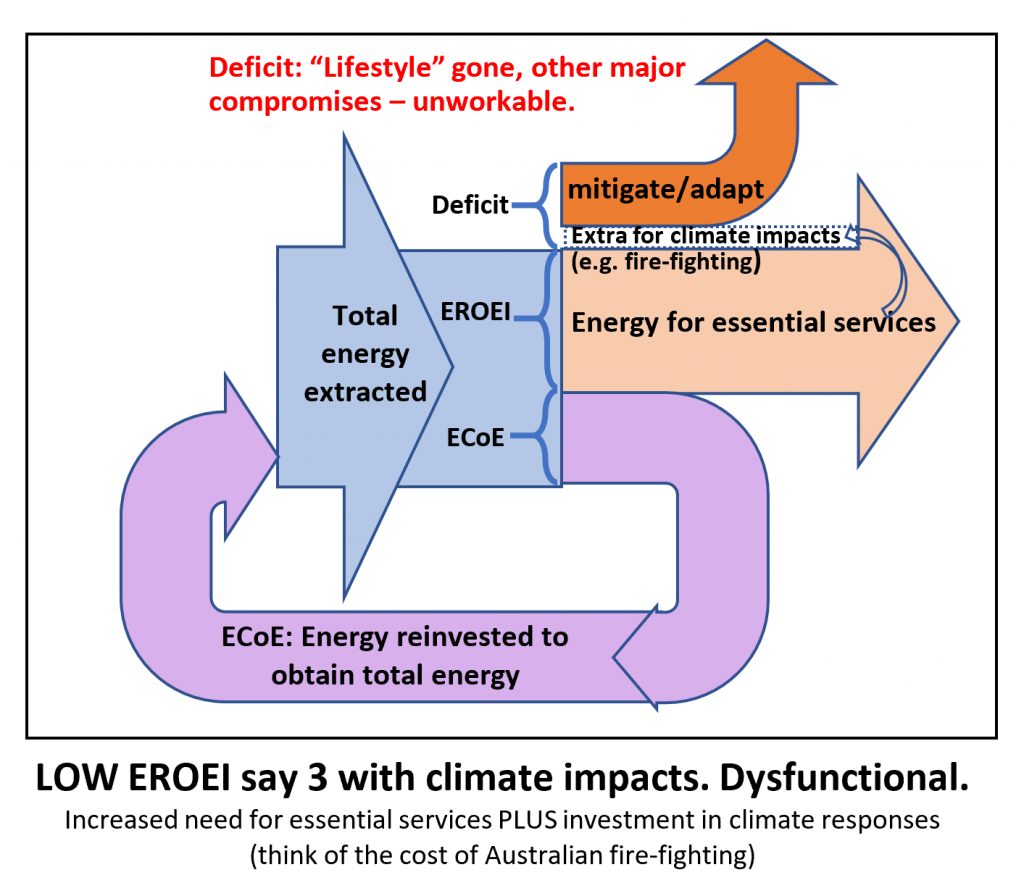

It takes energy to make energy available (e.g. to build and operate a dam and distribute its electricity). Our economy is driven by the surplus energy left after accessing and making it available.

The total energy extracted can be considered in two parts:

- “Energy Cost of Energy”, or ECoE, (bottom line of formula. e.g. the energy needed to extract, refine and distribute petrol)

- “Energy Return on Energy Invested” or EROEI (or EROI), the surplus energy then available for use.

- EROEI is also often considered in two parts: a) the energy for running essential services (police; growing food, infrastructure; government; etc.) and b) the energy left, available for culture, lifestyle, social institutions etc.

The EROEI of hydro power may be almost 100 (i.e. 1 kW used to generate and distribute creates 100 kW surplus), as were the early oilfields. Progressively, however, EROEI gets lower. (i.e. it takes more energy to get the energy, which leaves less to use. See separate diagram.) For the same essential services, the net effect is less surplus energy available for lifestyle (or vastly expanded energy sources to keep delivering the same energy surplus).

And energy professor Charles Hall, referencing nine specialists from different disciplines, writes

While each acknowledges that other issues, such as human culture, nutrient cycling, and entropy (among many others) can be important, each is of the opinion that it is energy itself,

and especially surplus energy, that is key.

Survival, military efficacy, wealth, art and even civilization itself was believed

by all of the above investigators to be a product of surplus energy.

The historical correlation of economic activity with energy abundance is clear, whether from firewood, horses, or even slavery (that horrendous engine of London’s 18th Century wealth). But the spectacular game-changer was fossil fuel, firstly coal (mercifully helping end slavery), then the astonishing energy density of oil (one litre of petrol providing energy equivalent to a month’s manual labour).

However, we commonly focus on the quantum of energy (e.g. oil reserves), but rarely on how difficult it is to extract. Energy economist and Life After Growth author Dr. Tim Morgan has termed “the killer equation” the relationship between the total energy extracted and the energy used to extract it. Ultimately, EROEI, or net energy gain, controls how much is available for society’s essential services, and then what is left for “lifestyle”

A big catch is that EROEI has been in long decline for traditional sources, and that of renewables (except hydro) is nothing exciting. The diagram shows our inexorable approach to the energy cliff, with potentially crippling constraints on energy, and thus economies. Even where there are abundant reserves (e.g. oil in Canadian tar sands), low EROEI also means escalating emissions and environmental devastation for every litre reaching consumers.

EROEI and the “energy cliff” Source Tullett Prebon Strategic insights 9

Factoring in the energy implications of climate change, things go from bad to worse (see diagram). We need more “essential services” (think Australian firefighting), plus massive additional works, like rerouting infrastructure, urban protection, or major electrification.

Even without EROEI, these present formidable challenges, but with increasingly marginal EROEI, this potentially leaves societies in energy deficit, with nowhere to turn, unable to complete critical work.

So where might we turn?

For a species habituated to trashing regional environments and moving on, this is our moment of truth, and it might come with a few surprises.

While things that seemed like opportunities might prove problematic, some that seemed problematic might prove to be opportunities.

For example:

- Transitioning off a growth-economy, a fundamental that needn’t have all the catastrophic downsides commonly portrayed, plus helping curb emissions and resource depletion.

- In New Zealand, reducing inequality should pay better across the board than increasing incomes, and will position us better to prepare for, and cope with, climate impacts.

- Our economy becoming more circular offers economic opportunities along with climate and resource benefits.

- Going to rehab for our consumer addiction, we’ll discover alternative paths to fulfillment, and even that consumerism can be counterproductive to wellbeing.

- Reprioritising energy use while we still can: our unwitting wastefulness of energy (e.g. driving 10 km uses the equivalent of about a month’s manual labour) gives us ample room to rethink and tighten our belts. Bodger wrote recently, The implication [of limitations of renewables] is that we have reached peak energy, and a transition to renewables means a reduction in energy supply into our economy”, a sentiment echoed by Hall who, also discussing energy, says “A critical issue is to determine how, if the pie is no longer getting larger, the remaining pie should be sliced.”

And, with fitting circularity, let’s end almost where we started, revisiting Rod Oram’s quote:

Too often we can’t even agree a simple set of facts about a problem

so our chances of solving it are minimal.

and rephrasing it as a fitting aspiration:

Let’s work hard at agreeing on relevant facts that will boost chances

of solving the climate crisis.

Leave a comment