Right now North American municipalities are suing farmers in their communities for polluting waterways with nitrogen says mixed farmer Gabe Brown. And yet there are simple techniques to prevent this happening while saving farmers money.

Gabe Brown addressing Stipa conference at the Eurimbula Hall near Molong, NSW. His insights into polycrops, sowing many species instead just one – a monoculture, led to a range of soil improvements which flowed into farm profitability and less stress.

Gabe Brown addressed 150 farmers deep in central NSW tablelands, Australia, sharing how productivity on his property increased with nothing more than seeds. Australian farmers desperate for new ideas for dealing with drought and looming nutrient regulations from amalgamating shire councils are sponsoring a new wave of innovative farmers not doing best accepted practice but getting better productivity and profit outcomes. Four years of droughts and hail forced Gabe to completely review his farming system. He is in such demand his global speaking schedule has a two year waiting list.

So why is he so popular? Firstly, he is a real farmer, owns and leases over 2,000 hectares in and on the outskirts of Bismarck, North Dakota at Brown’s Ranch. He does cash crops and livestock extremely profitably so has all the big toys but what is interesting is that his business uses no inputs; fertiliser and agrichemicals with the exception of occasional herbicides and livestock minerals. Furthermore, having 100,000 neighbours means greater awareness of how his stewardship impacts a lot of local people.

First thing farmers and scientists claim is that without inputs his operation will collapse. Yet Gabe is living proof that is not so, in fact it appears the opposite is happening. Scientists studying his farm (on Gabe’s terms) find he is regenerating his soils.

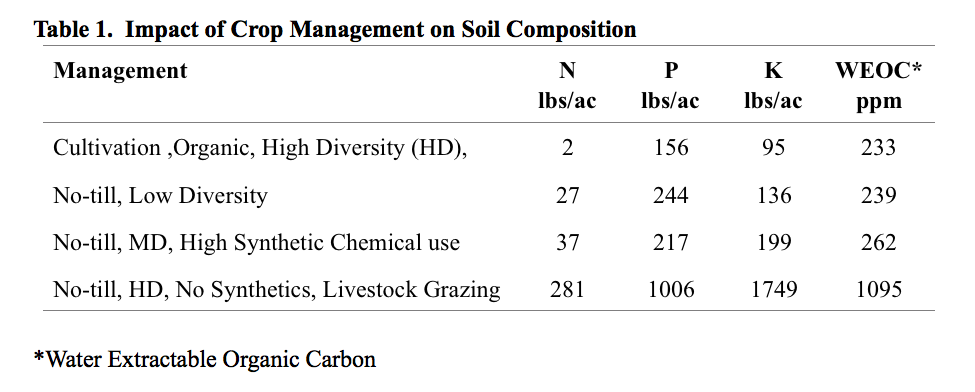

A recent ARS study by Dr Rick Haney (Table 1) shows this when comparing several other operations within 1,500 metres of Gabe’s property, all have same soil type and climate but different management. Gabe’s operation is gaining N, P, K and active carbon unlike other properties using best practice. He stopped cultivation in 1993, started using cover crops since 1998, hasn’t used fungicides or insecticides since 2000, nor any synthetic fertiliser since 2008. In 20 years soil organic matter has increased from 1.7% to averaging 6.3%, one paddock averages 11.4%. This is so fast scientists struggle to explain what is happening. Luckily there is no shortage of followers.

What triggered questioning management? In the late 90s Gabe experienced three drought years and a severe hail storm crippling his income four years in a row, he simply couldn’t afford normal fertiliser and agrichemicals. When he did go back to use them he was told by a soil ecologist any soil health benefits that accrued over that period would be lost due to negative effects of agrichemicals. He then started planting cover crops in 2-3 species mixes but it was a conference in 2005 that really got him excited.

He met Dr Ademir Caligari a Brazilian agronomist working for the UN and the world’s leading expert on cover crops. Two statements inspired; that cover crops could be grown in a rainfall range from 50mm to 5,000mm which meant he could grow them in his 400mm area. Secondly, nature always works in multispecies combinations, in other words 8, 10, 12 species mixes.

Armed with this insight, Gabe organised a local Soil District Health Board demonstration by planting several monocultures of common fodder crops and then one where all were sowed together. Winter of 05-06 had no snow and only 25mm between May and end of July. Yet at the end of that period combination crops tripled above ground biomass compared to best monoculture plots . As he argues, monocultures are detrimental to soil health because they don’t feed soil fungi. Agronomists seldom know much about soil fungi.

An example of a polyculture or cocktail crop. This particular crop has sunflowers, brassicas, cereals, and lupins. Gabe Brown’s experience is that cocktail crops triple biomass production in drought compared to monocultures of the species sown.

To prove his point he shows a picture of a tree growing out of a rock. There is no soil here, its the ability of trees to convert sunlight into sugars and create soil through feeding biology to extract nutrients from rocks that create such graphic images.

In fact Gabe often challenges conventional views. As understanding of mycorrhizal fungi improves he claims there will be no need for precision ag as fungi can transport nutrients across bigger areas than thought. Ploughing kills this free service. Soil aggregates can breakdown after 4 weeks, so farmers need to engage biology to continually rebuild them to enjoy these free benefits.

There is one caveat he warns farmers about going down this path. “If your seed rep is selling a mix without asking what your resource concern is, walk away. They won’t have your interest at heart”. If seed reps aren’t prepared to ask how a cocktail mix improves your soil they are not into regenerative agriculture. The secret is to know which environmental processes need strengthening and then linking that insight to plants which provide those services. Like everywhere else in farming, this thinking is not taught and seldom appreciated.

For example, grasses increase organic matter, buckwheat roots release tied up phosphate, daikon radish will grow out of the ground till it creates enough pressure to break through a pan but plant it after the longest day otherwise it seeds. Oats are great to stimulate mycorrhizal fungi, sunflowers for their deep taproot and feeding wildlife, the list goes on….

Gabe organises his covers crops from four basic plant types, cool season grasses and broadleaves, warm season grasses and broadleaves. New Zealand is prominently cool season which means there’s potential for adding in warm season species. Most of his mixes are between 15-25 species but occasionally tries out anything up to 75 species. His aim is for a growing root all year round, this cannot be accomplished with monocultures where all plant leaves are same size, pointing same direction, and are same maturity.

Gabe and his son Paul do a lot of experimentation, in fact their attitude is if they don’t fail at something they are not trying hard enough,

“Farmers need to be outside the box, who would ever want to be in it?” he says.

Therefore all projects are sown on highway edge to encourage discussion among travellers.

Diversity is so important. Gabe mentions a quote from Dr Jonathon Lundgren, “that for every pest targeted up to 1,700 beneficials are destroyed. Why not aim to provide a home for those beneficials to enhance services they provide?” he asks. His operation is home to 16 different dung beetle species, and as a result doesn’t use dewormers for his livestock. As he points out industry information highlights livestock drenches don’t kill dung beetles which is true. What is not said is how drenches make them sterile. It’s lack of transparency which is often behind farmer scepticism of industry products and advice.

Slow residue breakdown with accumulating litter is due to C:N imbalance. Ideally soil C:N should be 11:1 but high carbon crops will lift it 70:1. This is addressed by adding peas and daikon radish; peas to add N while daikon stores N for use the following season or next crop. Initially most properties need higher legume component to encourage rapid breakdown of litter, as high as 50%, of seed mix but as soil function improves that drops to 20%.

This oat crop near Eurimbula, NSW, was grazed to ensure litter covered bare soil between plants prior to planting next crop. Litter insulates soil against weather allowing soil surfaces to remain porous and not dry out. Sowing directly into litter reduces weed competition and favours sown seeds.

Gabe aims to direct drill into 75mm crop residue which gets consumed by soil life within a matter of weeks. In 1993 he sold all his cultivation equipment to buy a John Deere no-till seed drill. It cuts through trash with a single coulter, packing wheels hold litter down while seed is squeezed into the furrow followed by an off-set coulter to cover seed. All seeds big and small are mixed together and planted to a depth of 13-18mm. Germination of big seeds breaks ground open for smaller seeds to germinate in a sheltered microclimate. They’ve observed germination rates increase with higher soil function and now focus on sowing seeds in soil than waiting for all ducks to line up. He believes there are no benefits leaving seeds in bins.

Its livestock which bring soil life alive. Not only is plant diversity important for stimulating soil health, so is livestock diversity. Gabe and son Paul graze free range hens, pigs, sheep and cattle. Pasture fed pigs are their most profitable enterprise. They run mobs of 70-150 fed on cover crops, shifted every 3 days which stops them rooting soil and finished with their own grain.

Livestock are also used to change landscape species. They grazed cattle on a government site infested with Californian thistle to save spending $15,000 on herbicide. Within 12 months foxtail barley emerged creating a monoculture of grass, at 18 months forbs (tapped rooted plants as compared to fibrous roots of grasses. In a broader this term also refers to legumes) began appearing, at 24 months improved grass species emerged, and at 36 months beneficial native plants arrived. These changes occurred by grazing cattle at 100,000kg liveweight per hectare (equivalent of 222 450kg cows/ha) on long rotations.

As a result of his success, Gabe now attracts other business opportunities. One such project included building a local abattoir so he could sell his own label over the internet. He found a community 90 miles from his home prepared to donate land. He borrowed the operating capital and while this enterprise is not turning a profit yet it has a waiting list of 6 months compared to 13 months with the competition.

Gabe Brown represents a totally new wave of thinking in farming. Unlike much of agriculture and environmentalism which is talking about sustaining a degraded resource such as soil, it’s farmers like Brown who are inspiring farming communities to challenge industry information and advice to look at what services nature can provide and how that can improve soil function, lift profits, and lower labour and production costs.

Leave a comment