Microbes for control of plant pests and diseases.

All too often the story of an exotic species arriving undetected on New Zealand shores turns out badly for our environment. In the case of the Epichloë endophytes, however, these tiny micro-organisms have hugely benefited pastoral farming in New Zealand and helped us understand how endophytes might hold the key to sustainable agriculture globally.

Endophytes are fungal or bacterial microbes that live for some or all of their life cycle inside plants. Associated with the majority of plant species in both natural and managed ecosystems, they are generally located between the cells and have no detrimental effects on the host plant. Indeed, they can confer many benefits, promoting plant growth and survival through the inhibition of pathogens and invertebrate pests, the removal of soil contaminants, and improved tolerance of low fertility soils, extreme temperatures and low water availability.

While fossil records of endophytes date back more than 400 million years, it is only recently that these endophytes and their bioactive products have received meaningful attention from the scientific community. As crops were domesticated it is likely that many of these valuable plant-microbe interactions were lost and that this gained pace with the increased use of agro-chemicals, many of which would have been detrimental to the microbes’ survival. In essence, we unwittingly lost the use of nature’s goodness and became more and more reliant on agro-chemicals. Now with many of these chemicals being more tightly regulated or removed from use due to environmental concerns such as the decrease in pollinating bee populations, we are going to have to work to regain the use of microbial endophytes to combat serious pests and diseases.

Happily, we are not starting from scratch on this important work, because microbes have been used as an alternative to synthetic chemistry for many decades. Predominantly this has been where farmers choose low chemical input systems such as in organic farming, in low input regions where the cost of pesticides is high, or where there is no acceptable pesticide available for the control of topical pest and disease. But all too frequently the use of these conventional microbial biocontrol solutions are diminished by environmental variables such as temperature extremes, low moisture and competition from other microbes. This is particularly the case where endophytes have a free living stage outside the host plant. To combat this, Grasslanz Technology, with its research partner AgResearch, has focused on working with “obligate endophytes”, that have no free living stage in nature, spending their whole life cycle in symbiosis with their host plant.

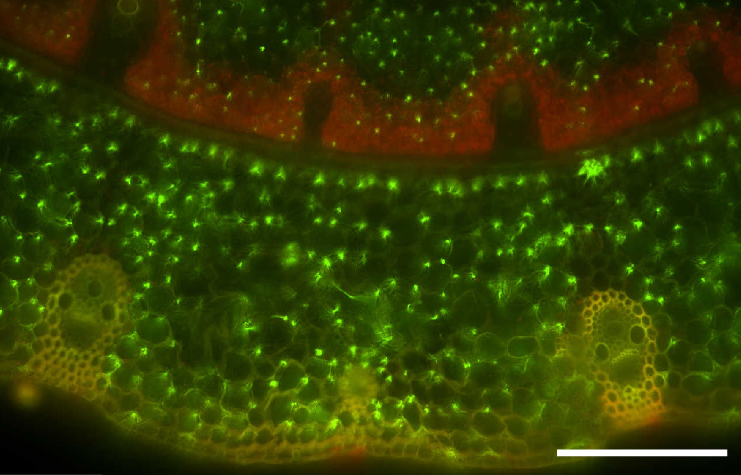

Epichloë hyphae in grass leaf tissue – a cross section through a leaf tiller showing hyphae as green dots

One of the most commercially successful plant-endophyte partnerships Grasslanz has worked on involves Epichloë, a species that spends its life cycle living in temperate grasses such as perennial ryegrass. New Zealand pastoral agriculture is heavily reliant on perennial ryegrass, brought here by European settlers in the nineteenth century. It is critically important for not only the dairy industry, but also for sheep and beef finishing systems, and has been estimated by NZ Institute of Economic Research to be worth $5.5 billion to New Zealand’s GDP.

What we didn’t know in the nineteenth century when perennial ryegrass arrived, was that the tiny Epichloë endophytes had come along for the ride. In fact, they were not discovered until about 35 years ago, and initially because they were identified as causing ryegrass staggers disease and heat stress in grazing animals.

Early work from AgResearch identified the bioactive compounds that were responsible for causing these and developed alternative animal-safe Epichloë strains.

This world-leading R&D laid the foundation to identify strains that produce other bioactives that deter major grassland insect pests, such as Argentine stem weevil, African black beetle, pasture mealy bug, root aphid and porina.

The Argentine stem weevil – a major pasture pest in New Zealand perennial grass pastures

2001 saw the commercial release of the endophyte strain AR1. It was a technological breakthrough, providing resistance to Argentine stem weevil and avoiding the need to frequently resow grass, reducing fly strike and no longer causing ryegrass staggers or heat stress. Trials showed a 10% increase of sheep live weight gain, an increase of 9% milk solids in dairy herds and an overall 22% increase in returns to farmers through using AR1 rather than the toxic wild type endophyte.

AR1 had an extraordinarily rapid uptake with New Zealand farmers and by 2008 was included in 70% of the proprietary perennial ryegrass seed sold. It is now licensed to 10 companies and marketed in more than 30 cultivars, used in New Zealand and exported to Australia and Chile. It is currently being evaluated for use in USA, Europe, Uruguay and Argentina.

Despite this success, however, the search for the next “superstar” endophyte continued. Next out of the blocks was endophyte strain AR37, which produced entirely new bioactives that confer a wide range of tolerances to insect pests, including Argentine stem weevil, black beetle, root aphid, pasture mealy bug and porina. Field tests also showed improved growth and drought tolerance, demonstrating persistence and higher yielding at critical times of the year.

Since its first release in 2007, AR37 has been included in more than 10 ryegrass cultivars. Uptake has been very strong: AR37 has had a predominant role in re-grassing of dairy pastures north of Taupo and the Central Plateau while AR1 is now down to about 30% of proprietary ryegrass seed sold. Again, the figures speak for themselves, with sheep growth during the summer and autumn on pure ryegrass pasture averaging 29 g/day for the toxic wild type endophyte, compared with 74 g/day for AR1 and 93g/day for AR37.

AR37 (middle plot) compared with ryegrasses with other endophytes

There is little doubt that these Epichloë endophytes have made a significant contribution to wealth creation in pastoral farming in New Zealand and now the global opportunity beckons. New Zealand is leading the way in commercialising obligate endophytic microbes for use with temperate grasses and is now working with offshore partners to extend that into other crops of economic importance, such as cereals, maize and brassica crops and tropical grasses. If we can identify similar obligate endophytes in these other species and harness them to protect these crops from pests and disease the global impact could be huge, enhancing animal welfare, increasing financial returns to farmers and reducing pesticide and fungicide use. A vital sustainability “triple win” for micro-organisms that were for many years the hidden stowaways of modern agricultural production.

Leave a comment