If there is one thing that farmers have taken for granted for centuries, it’s the need to till or cultivate the soil before sowing crop seeds. And there’s nothing more fundamental to producing food than sowing seeds. Even most of the meat we eat requires sown seeds to feed the animals. It’s only fish and nomadic land animals that graze wild pastures that escape mankind’s seed-sowing step in the food chain.

It’s interesting to also note that the part of plants that humans most commonly eat is their seeds. Nearly 70% of the world’s food, for example, is cereals and the only parts of cereal plants that we eat are their seeds.

But the seed-related issue that affects climate change most is what we do to the soil in order to sow new crop or pasture seeds in the first place.

Soil is a living entity and its single most important energy source is carbon. All plants that grow in or on soil contain carbon. But they don’t get much of this carbon from the soil. Instead, they get it from carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. Through sunshine, chlorophyll in the green leaves of plants create a process called photosynthesis in which the leaves capture CO2 from the atmosphere, combine it with water, hydrogen and other nutrients and turn it into carbohydrates.

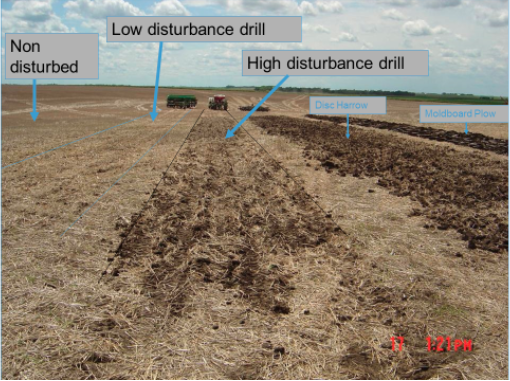

Examples of how different field machines disturb the soil during crop establishment, which in turn affects CO2 losses. Home-gardener practices that produce the same results, do likewise.

(Source, Dr Don Reicosky, US Department of Agriculture, Minnesota, USA, 2016)

Amongst other things, this is nature’s way of removing carbon from the atmosphere that is put there by numerous other processes, both biological (such as breathing, flatulence and the decomposition of organic material) and non-biological (such as combustion and volcanic eruptions). The current problem is that mankind controls much of the combustion and has increased this at a rate greater than green leaves can now recapture through photosynthesis.

The end result is an accumulation of more CO2 (the main product of combustion) in the atmosphere than the dwindling number of plants that are left, can remove.

The processes are much more complicated than that, but in simplistic terms this is the heart of the present problem. And since atmospheric CO2 has a major effect on climate change, most of our focus (understandably) has been on reducing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

But increasing the amount of carbon in the soil is just as (some would argue – more) important.

The good news is that there are ways and means of doing both at the same time using agricultural crops. The trick is to grow food crops in such a way that they recapture more CO2 from the atmosphere than is emitted into the atmosphere during ground preparation and the plant’s growth cycle, but still continue to feed us at the same time.

Sound like a tall order? Perhaps not as tall as you might think.

- Conventional tillage or cultivation (or just digging the garden) usually introduces more air into the soil than is desirable for its sustained health. It results in oxidation of some of the existing soil organic matter (which is about 40% carbon) into the atmosphere as CO2.

- On a farm scale, about 3 tonnes of carbon is lost per hectare when the soil is ploughed and cultivated. If this is added to other losses, the total carbon lost from the soil when each annual crop is grown using conventional cultivation (or digging the garden) almost invariably exceeds any carbon gained during the growth of the plants.

- The problem is that CO2 is a colourless, odourless gas and therefore no-one sees it leaving the soil. The dust we all see behind a tractor cultivating a paddock is just that – dust.

- Nor do you see CO2 as smoke when carbon is burnt elsewhere. What you see leaving a chimney or fire as smoke are the tiny particles of solid contaminants, some of which might be carbon, but the CO2 amongst them is invisible.

- The exhaust of a well-tuned car is usually invisible because engine combustion and exhaust emissions are now so carefully controlled that almost no unburnt visible particles exist – just invisible carbon dioxide and water vapour (which are non-toxic) plus (highly-toxic but also invisible) carbon monoxide.

On the other hand, when a farmer undertakes low-disturbance no-tillage or a gardener adopts a “no-dig” gardening policy by scooping out only enough soil to plant individual plants or seeds rather than digging the whole garden, there’s very little CO2 emitted because very little air is introduced into the soil.

- This is STEP 1 of low-disturbance no-tillage.

- STEP 2 is to cover the soil where the seeds are sown with an organic mulch. This can be done on a farm scale using specially designed seed drills that don’t block or push the straw from the previously-harvested crop aside when inserting the seeds beneath these residues, which are purposely left lying on the ground. Gardeners achieve the same thing by placing (or replacing) organic mulch over the soil where the seeds were sown.

- STEP 3 is handled by nature utilizing the billions of soil microbes and small animals that inhabit healthy soils, especially earthworms. The latter feed on organic material and come looking for it on the surface of the ground, especially at night. But other microbes decompose the organic matter too and, in the process, create exudates that bind soil particles together, forming desirable soil structure. In other cases, the nutrient-rich compounds attach themselves directly to soil minerals.

- Although this microbial activity also produces CO2 above the ground from respiration, the quantities are far less than if the soil had been disturbed and aerated.

- All of this carbon-rich material is gradually transferred (sequestered) into the soil to start rebuilding its organic content. And since organic matter is the main foodstuff of soil microbes, the beneficial process becomes self-sustaining and cumulative.

- It is not a process that can be accelerated by digging (or working) the organic matter into the soil because the aeration from doing so is likely to oxidise more existing carbon from the soil than is being gained from burying the mulch in the first place.

- STEP 4 is to ensure that the post-harvest residues of the crop being grown are spread evenly on the soil surface on both a farm and garden scale so that they can become the source of carbon for the next crop cycle.

The essential point is that when most food crops are grown on a farm scale, the total biomass produced by these crops is comprised of approximately 50% seeds (that we eat) and 50% straw, stems, leaves, roots and seed-husks that we do not eat (collectively referred to as crop “residues”).

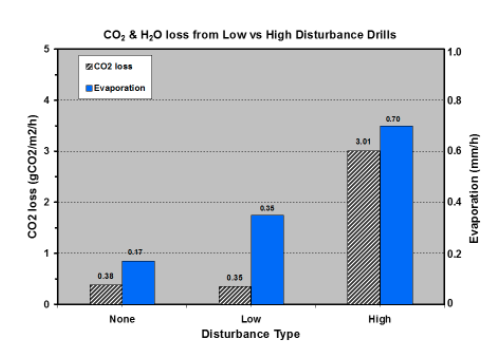

he effects of soil disturbance on emissions of CO2 and water vapour

(Source, Dr Don Reicosky, US Department of Agriculture, Minnesota, USA, 2016)

We harvest and eat the seeds as intended, regardless of whether the crop has been grown by convention tillage or low-disturbance no-tillage. But more often than not with conventional tillage, we waste the residues by burning or ploughing them in. In some countries they are removed as a convenient source of low-quality animal feed, bedding or fuel. But one way or another, by removing them the soil microbes are denied access to them and by doing so farmers gradually strip the precious carbon from the soil and transfer it to where no-one wants it – into the atmosphere.

Low-disturbance no-tillage changes all of that. With this reasonably recent technique, the soil is never ploughed and is only disturbed by the minimum amount necessary to implant the seeds and fertilizer. In the process the foods crops still feed us, but the soil can annually gain about 500 kg of carbon per hectare each seeding event compared with loosing up to 2,000 kg carbon per hectare to the atmosphere when the same soil is cultivated. Even more carbon can be added to the soil if a cover crop is grown between each food crop without disturbing the soil.

Growing a cover crop in the home garden is also beneficial, but digging it in negates almost everything gained. It is better to cut it before it seeds and leave it to decompose in situ.

All other forms of “reduced tillage”, “conservation tillage”, “strip tillage” and “minimum tillage” are only partly effective in what they do to soil carbon. Some may result in a small net gain in soil carbon, but most will not do so. They may reduce the net losses but they seldom reverse them.

And cover crops are mostly impractical with conventional tillage because the above-ground plant material needs to be removed before the soil can be ploughed a second time.

The United Nation’s FAO estimates that, if we continue to rely on conventional tillage, there are only 80 harvests left in the world. The problem is that serious.

Low-disturbance no-tillage however, allows us to feed ourselves sustainably. Better still, the healthier soils that result almost invariably produce higher-yielding crops anyway, which is good for both farmers and food-consumers alike. And because we’re part of the global village, we can lead the way in helping to feed the extra 50 percent of mouths in the world by 2050.

But the best thing of all is that the specialist equipment for achieving true low-disturbance no-tillage almost everywhere in the world was invented in New Zealand and continues to be supplied from here as well.

We may need help to keep it here before someone from overseas comes along and buys our entire supply chain as so often happens.

Leave a comment