Ancient Greeks worshipped Athena the goddess of wisdom, craft, and war, she was the protector of ships and of weaving (the sail cloths that propelled the ships). According to Elizabeth Barber, professor emerita of linguistics and archaeology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, textile production is older than pottery and perhaps even older even than agriculture and stockbreeding. Textiles are our earliest and most enduring form of technology, more ancient than bronze and as current as digital currency. Before metal currency was invented cloth was used for transacting trades, now Bitcoin pioneers have adopted the term ‘weaving’ rather than ‘mining’ as their metaphor for recording transactions on Bitcoin’s socialised ledger.

Today’s computer technology borrowed from the binary system of weaving and directly from the punch card technology developed for the production of Jacquard cloth by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801. Our language reflects the profound impact of textiles on humanity and society’s development, words like fabricate from the Latin word fabrica ‘something skilfully produced’, text and textile from the verb texere,‘to weave’. We speak of hanging by a thread, or being frazzled, of catching a shuttle, of spin-offs, and looming deadlines. Textile terminology is so deeply embedded in the vernacular we give little thought to its genesis.

From its position at the cutting edge of technology for centuries, some sectors of the textile industry now appear to be lagging far behind. Li Edelkoort, legendary trend forecaster laments in her 2015 Anti-Fashion Manifesto that “Fashion is old-fashioned” and that “It is no longer part of the avant-garde”. Observing that what once was fashion has turned into garment consumption, with an estimated 100 billion units of clothing produced annually, it’s hard to argue with her. The child labour in northern English Victorian era mills and slavery in the cotton fields of America has not been eradicated, just moved, offshored away from the first world gaze to places like Bangladesh, Vietnam or Cambodia where production regulations are light and minimal wages keep workers in poverty.

The fashion industry is now valued at about 3 trillion per year, container after container of clothing leaves South East Asia and is shipped across the world to Europe and the States and the South Pacific where the latest outfits are worn for a period (an average Zara garment is worn 6 times). Then about 70% of the worn garments are shipped to third world countries, where the uncontrolled export of our waste clothing has decimated local textile industries and created an industry of poverty where people try to etch a living out of the resale of used garments, this has resulted in significant social impacts through the closing of local industries (which cannot compete with the import of cheap clothing) and the loss of skilled jobs to significant environmental effects from the dumping of unwanted used clothing.

People want to do the right thing, as is indicated by the large volume of used clothes donated through clothing bins rather than just thrown out. In reality, they are providing free stock to multi-million dollar businesses which then on-sell the majority of this clothing to poor second-hand clothing traders on foreign shores. The issue is so significant that in 2016 a block of East African Government’s proposed a ban on the importation of second-hand clothes, but a counter move from powerful US rag traders to have trade agreements rescinded to enable the continued dumping of waste clothing on those less fortunate looks far from benign.

New Zealand is part of this global system, churning through about $4 billion worth of clothing a year. So, when we have worn the latest outfits and moved on to the next season where do billions of dollars worth of our clothing go? Auckland Council estimate discarded textile and clothing waste at about 9% of landfill and is their fastest growing waste stream. Our donated clothes are sold into the Pacific, New Zealand exports a cool $14million in used clothing a year to Papua New Guinea alone.

While our domestic clothing consumption is eye-watering, commercial textile consumption is estimated to be 40 times greater by volume. We can start to comprehend the enormity of the challenge we are facing. The majority of corporate clothing is made from polyester, these uniforms when assigned to landfill do not break down and are still going to be there in 50-100-500 year’s time, leaving a long legacy. We only need to look to France for a more effective and workable system, laws on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) such as their EcoTLC system has resulted in significantly reducing clothing to landfill. Each garment introduced to the market is charged less than a euro cent which in turn pays for the financing of research, design and the development of reprocessing capability, converting waste textiles into inputs for other products.

The recently released Pulse Report on the State of the Fashion Industry, predicts the industry aims to double its use of polyester by 2030, placing their hopes on the emerging fibre to fibre technology which uses green chemistry to break down used polyester to its molecular componentry and then be reformed back into polyester without the loss of quality. Promoting the concept that clothes could be “infinitely recycled” allowing big brands to continue their growth strategy, guilt-free.

But this ignores the environmental impact of the use and laundering of synthetic clothing. Microplastic fibres from clothing and other plastics are so prevalent they are now a common contaminant in our drinking water and food sources. Tap water samples from over a dozen countries have been analysed with over 80% contaminated with micro-plastic fibres from clothing and other plastics. According to Greenpeace’s 2017 ‘Fashion at the Crossroads’ report “Recent studies of the plastic waste along the western coast of Sweden found that more than 90% of the microplastics found in ocean surface waters (which are themselves a portion of overall marine plastics) consisted of synthetic textile fibres.” While the focus of the fashion industry is on recycling of synthetics, the green chemistry recycling of clothing and textiles made from natural fibres is also developing rapidly.

Cognisant of these issues, a collaboration of prominent New Zealand organisations including Fonterra, Alsco NZ and Wellington City Council formed to create a step change in how end-of-life clothing is managed. The Formary was approached to lead the programme with the aim of reducing environmental impacts and producing social and financial benefits for New Zealanders. Stage One audited the waste textiles being generated by the participating companies, analysis by weight and fibre type gave a clear indication of volumes and fabric types and the processing capability required. Then reprocessing solutions were assessed and a reprocessing model designed. Phase two saw the development of a scalable model forend-of-life clothing and the refinement of the operational model which converts clothing into valued fibre feedstock for a range of industries. The programme has now been opened to other organisations, assisting them to meet waste minimisation targets and customers’ expectations for responsible management of end-of-life clothing. Most countries are facing the same challenge of clothing over-consumption and limited, disconnected solutions. Approaching the issue from a systems perspective has attracted international interest in the programme.

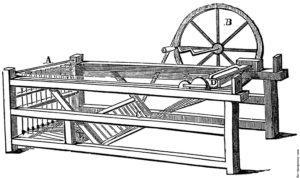

Spinning Jenny – One of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution

Spinning technology was the catalyst that sparked the industrial revolution, weaving punch card technology the computer age, the invention of polymers and high tech fabrics have enhanced mankind’s physical performance on this earth and beyond. Since time immemorial textiles have remade our world, repeatedly revolutionising society. Our over consumption of clothing is now impacting the earth’s ecology, it’s time for the textile industry to do what it does so well and usher in a new revolution, this time a restorative one.

Leave a comment