In late November 2017 a small group of people at Middlemore Hospital celebrated a remarkable achievement – a reduction in the Carbon footprint of the Counties Manukau DHB by 21.2% in just 5 years.

That work which began in 2011 was fuelled by the good will of a small group of ordinary people: doctors, nurses and others who took it upon themselves to take action on Climate Change by doing the same simple things at work that so many were already doing at home; conversations about small stuff in the main, recycling and reducing waste, then a growing desire to learn more about our own Carbon footprint and the relationship between Climate Change and healthcare more generally.

Those conversations continued and soon we were meeting with people from other organisations to see what they were doing; we met representatives of large corporates in their offices and over Yum Cha lunches, but as it so often happens, the way forward was in front of our eyes. A short time later in the dead of the night in the middle of a long shift in the ICU I was in conversation with our Charge Nurse and discovered that her sister was part of the small team that ran Enviro-Mark Solutions Certified Emission Measurement And Reduction Scheme (CEMARS).

Credit: Tim Bish – Unsplash

That programme was established about 8 years ago to work with organisations from the public and private sectors to help them understand the nature of their Carbon footprint, to measure it and to manage it down over time. CEMARS now have over 300 members in NZ including Auckland Airport, Auckland Museum, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Toyota, BMW, Kathmandu New Zealand and many more small and large businesses; and the methodology that underpins their process has been franchised out to other organisations who do the same all over the world.

A few months later, after some strategic lobbying and a minor tussle with our Board we joined and yes, you could say the rest is history, but that would underplay the ongoing expertise we get from our relationship with Environmark and their network, the hard work of many of our team and the difficulty of the journey ahead.

In developed nations, healthcare accounts for between 5 and 8% of a nation’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and uses twice as much energy per square foot as traditional office space. It’s specific Carbon footprint has been well described.

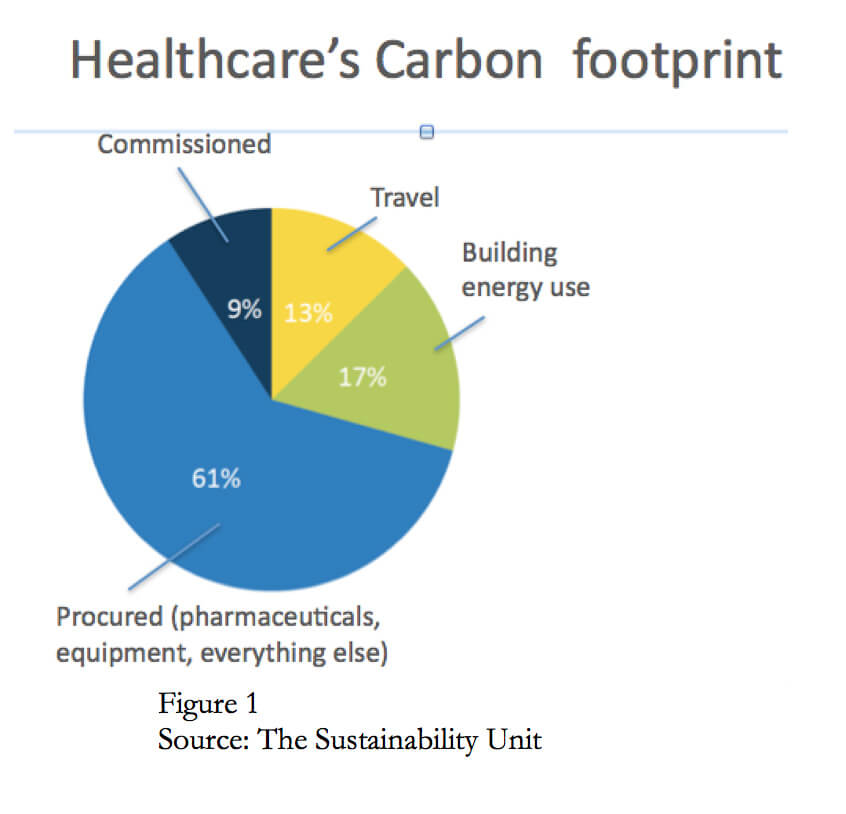

See figure 1.

Our success to date has been born out of a bottom up, grassroots movement that emerged and grew over time. Led by our sustainability officer Debbie Wilson and a small team, we began by harnessing the energy of many of our staff to establish “green teams” in different parts of our organisation and concentrated our efforts on reorganising and focussing existing resources to achieve specific goals in areas that did not require a significant upfront investment.

Credit: Ash from Modern Afflatus – Unsplash

Over the years our work has steadily gained traction within the DHB, reeling in more and more people keen to help. As a result, we have huge support from our front line staff and have reduced waste, increased recycling, massively improved energy efficiency thanks to our Energy Manager and developed a travel strategy for staff, patients and the public. Whilst we are thrilled with our progress, there is the potential to do much more.

Waste, energy and transport make up only 30% of a healthcare system’s Carbon footprint (Fig 1)), over 60% is related to procurement or more specifically to the life cycle costs of the medicines and the myriad bits of equipment and devices we use in everyday practice. So, the purchase cost of those items should take into account the Carbon cost of each item’s manufacture, packaging, transport, use and disposal. This approach opens up a raft of new opportunities to do things differently, e.g. the chance to reassess the benefits of using multi use instead of single use instruments to decrease overall costs and improve value.

So, if the healthcare sector is to play its part in helping the nation become net Carbon neutral by 2050, we will need changes in government policy to ensure that our major purchaser of medicines and devices, Pharmac, direct their considerable expertise and muscle to include carbon and lifecycle costs in their purchasing decisions.

Until that happens we will still do what we can locally. A beautiful example of that is from the world of anaesthesia, led by Dr Rob Burrell. He simply made his department aware of and tracked the use of two commonly used anaesthetic drugs Desflurane and nitrous oxide, both of which carry a massive carbon footprint. These are gases that are inhaled by patients to keep them asleep during surgery. Desflurane has an emission profile 200 times greater than a similarly priced drug Sevoflurane that does much the same thing. Once our staff became aware of the carbon cost of Desflurane its use dropped off dramatically. The same occurred with nitrous oxide which is also a significant part of NZ’s agricultural emissions – it hangs around for 140 years, destroys the ozone layer in the atmosphere and has an enormous warming effect in addition to its massive Carbon footprint. Now that staff are aware of that, nitrous oxide is rarely used. These changes in behaviour are tremendous examples of the beneficial consequences of triple bottom line reporting and thinking.

It is heartening to know that the work we are doing at Counties is being picked up, matched, and in some areas exceeded by an increasing number of DHBs, with Auckland and Canterbury DHBs now joining the CEMARS community, and that our network is becoming stronger thanks to the support of many including organisations like Ora Taiao, the NZ Climate and Health Council. The gains that we have made at Counties should now be relatively easily replicated across the whole of the health sector, but even if that happens, it will not be enough.

We have come to a hard point in our conversation, forced to decide what we choose to value. There is little chance that NZ will become net Carbon neutral or that our DHBs and other parts of the public sector will be able to contribute meaningfully to that goal until we have a change of heart and carbon costs become part of the value equation alongside fiscal and social costs to assess outcomes – otherwise known as “triple bottom line reporting”. If we fall short we will be in a lose-lose situation, out gunned by innovators abroad, forced to pay more through the purchase of scarce and expensive carbon credits whilst subsidising local activities that will still rely on fossil fuels.

The argument for accounting for Carbon in health is strong. There is a welcome and proven double benefit from reducing emissions from this sector because what is good for health is also good for the environment; and vice versa, what’s good for the environment is also good for health. So interventions to drive down our GHG emissions will further incentivise the kinds of changes in healthcare that we have been striving to achieve for a very long time.

This relationship has been extensively explored by many commentators around the world but perhaps is best articulated in the work of the UK’s Sustainable Development Unit, a small independent group that sits outside of the English National Health System to advise them on specific actions that organisation can take to help the UK reach its own emissions target.

These activities fall into two big areas where Carbon can be accounted for and substantially reduced whilst improving health outcomes and decreasing costs in the system. The first is to reduce overall intervention rates by actively promoting, establishing and collaborating in wellness and prevention programmes; by redesigning existing care pathways to reduce waste and carbon, e.g. moving services closer to where people live and work; by using telehealth; and by seeking out low carbon alternatives in what we procure, purchase and use. The second major area for intervention is to ramp up the work that we are have been doing at Counties, to further reduce the carbon intensity of our infrastructure – to eliminate waste, reduce energy and travel.

On reflection, we were a naïve bunch when all of this started in 2011, but not now. We have come a long way and are very different people, with expertise, knowledge and a bold aspiration to do more and do better. We not only understand the complex relationship between healthcare and Climate Change, we are we are well placed to lead the public sector in its efforts to accelerate NZ’s ability to reach its own target before the due date of 2050, something that will save the country tens of billions of dollars.

Underpinning that confidence sits a sound understanding of the specific actions that will be necessary to achieve that goal but perhaps more importantly the benefits of the change in mindset that will be necessary for that to happen. When you get this, I mean truly get it, and not just do this as a compliance thing, you start to understand how fragile things actually are for us as people and the importance of the interdependencies that exist between each of us, and between us and the environment that sustains us. This revelation changes the way we see the world and what we value and opens up a realm of opportunity that others struggle to see.

By way of example let’s reflect on the different outcomes that might have been possible with triple bottom line reporting in two specific instances where value-for-money-alone-thinking prevailed.

The first, the disastrous Compass food deal: worked up under the umbrella of commercial sensitivity, this was signed off by Health Benefits Ltd (HBL) on behalf of the previous government, contracting the UK multinational Compass Foods to supply inpatient meals, and meals on wheels, for all 20 DHBs, for an eye-watering 15 years. Picked up by only six health boards, the three Auckland metro DHBs, supported strongly by Lester Levy former Chair of both Auckland and Waitemata and interestingly a previous Board member of Health Benefits Ltd; Tairawhiti; Nelson-Marlborough; and Southern DHBs. As I understand it, these six organisations now carry the liability for all 20 DHBs for the duration of the contract.

In late 2014, our sustainability group at Counties argued against that contract: the food was terrible; the duration of the contract ridiculous but our main objection was because the deal effectively cut our local suppliers out of the economy created by the biggest employers in our regions and did nothing to promote the well-being of local communities.

We argued that if we properly assessed social and environmental costs as well as fiscal costs, the contract with Compass could have been turned into an opportunity to promote healthy eating and put money into the pockets of the local community instead of becoming the liability that it now so clearly is. A stunningly innovative and mutually beneficial result could have been achieved by ensuring that where possible all food was sourced locally; our food waste composted rather than sent to landfill; and that compost returned to the suppliers to grow more food.

A second example: the leaky and moldy buildings at Middlemore (and most likely elsewhere across the public sector). Buildings account for up to 40% of our country’s Carbon footprint and the operational costs of a building over its lifespan is usually 10-12 times more than the initial cost of its construction. Requests for new capital investments (new buildings) in health are referred to the Capital Investment Committee and they in turn provide advice to the Director General of Health and the Ministers of Health and Finance to ensure that government objectives are appropriately prioritized and met in the decision-making process. This is a reliable and sound system but sadly the process is skewed towards valuing short term costs over opportunities for longer term savings.

If social and environmental costs had been factored into those decisions, and we paid more up front to specifically realise the substantial long term returns from reduced operational costs and improved productivity that we know exist from these long term investments, we would all be better off.

The benefits of this approach have been elegantly demonstrated in a paper recently published by a group of experts from Harvard University. They examined a subset of green-certified buildings over a 16-year period in six countries including the US, China, India, Brazil, Germany and Turkey. In that time period these Green Buildings saved $7.5 billion in energy costs and $5.8 billion in climate and health costs.

Credit: Vladimir Kudinov – Unsplash

In the U.S. alone the health benefits derive from avoiding an estimated 172–405 premature deaths, 171 hospital admissions, 11,000 asthma exacerbations, 54,000 respiratory symptoms, 21,000 lost days of work, and 16,000 lost days of school.

It is clear that NZ will not become net Carbon neutral by simply saying it will. We will only reach our goal if all parts of society contribute including the considerable public sector, which when it comes to change, tends to be more conservative than businesses in the private sector.

Our story is a simple one that started with a small group of committed people, a goal, a method and with measures to guide our progress. We believe that the gains we have made to date are there for all to achieve and now 6 years on we can clearly see the way forward, for us in healthcare and indeed for the public sector at large.

So where to from here?

Our network is strongly advocating for:

- All DHBs to join the CEMARS programme, to use the same definitions and measures to work together and learn from each other, to accelerate each other’s progress in reducing GHG emissions, improve health outcomes and reduce costs. We believe a consistent approach typified by the CEMARS methodology of target setting, measurement, management and third party independent verification of progress to reduce GHG emissions should be adopted by the entire NZ public sector for those very same reasons.

- The Ministry of Health actively promote and assist DHBs in this work.

- Healthcare organisations and especially DHBs should develop their own Climate Change adaptation and mitigation plans as well as a detailed plan for themselves to become net Carbon neutral by 2050 and that these plans be shared, improved and made public.

- The Government and Ministry of Business and Innovation adjust national procurement requirements to mandate Pharmac and other public sector procurement agencies to account for environmental and social costs in its purchasing processes.

- The detailed business cases for new capital works across the public sector must include options that clearly define the long-term savings in operational costs and improved productivity that arise from differing levels of upfront investment in the design and build process and that this approach be standardised, e.g. that taken by The Passive House approach or through the Greenstar 1-5 rating, which provides a robust framework for standards, quality, warranties and accountabilities throughout and a means for ongoing comparison and improvement in the design and build of future infrastructure.

Of all of the things that I have been involved in throughout a long career in health, this collaboration has been the most enjoyable, optimistic and collegial experience that I have had, and I think it’s going to get better from here. Please join us in this work to make NZ a better place for all.

Leave a comment