The Carbon Footprint Standard is one year old

In August 2018, the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) published the first standard for carbon footprinting of products: ISO 14067:2018. On the ISO’s anniversary together with Daniele Pernigotti, the convenor of this ISO working group we look back and discuss why the standard is more relevant today than ever.

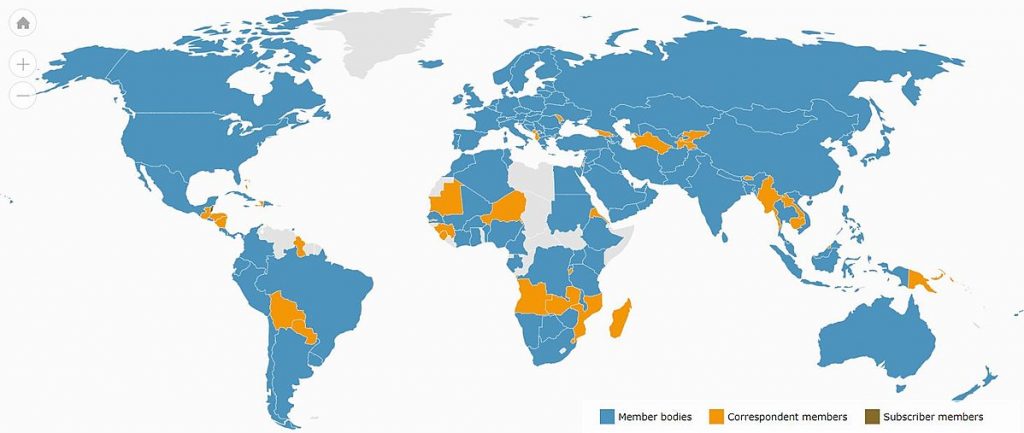

The standard development process was lengthy but thorough. Daniele and I contributed for nearly 10 years, Daniele as part of the Italian delegation and myself representing New Zealand. While the first attempt at reaching consensus amongst the over 50 contributing countries came up short, it was apparent that there was unanimous agreement on the overall objective.

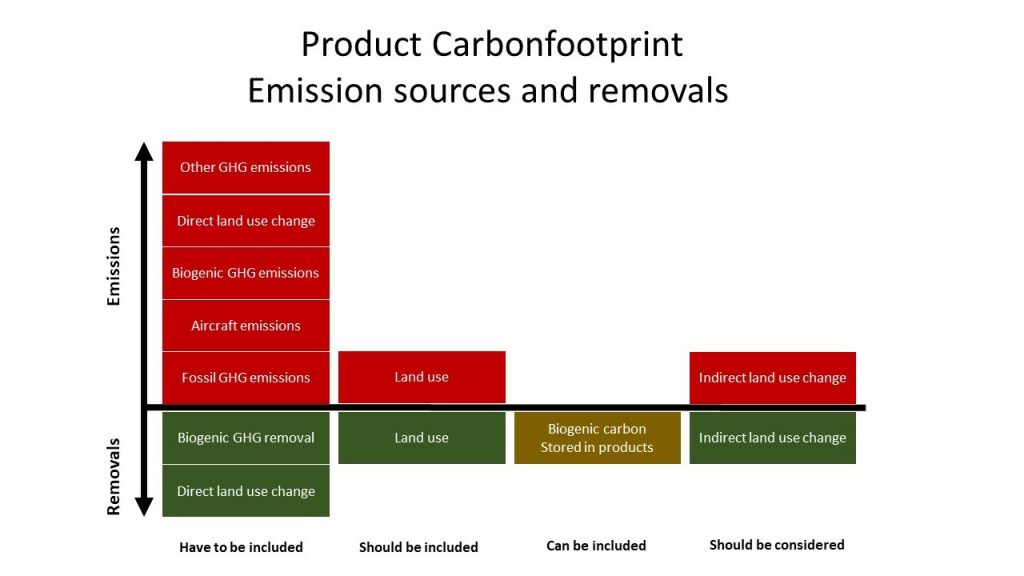

I see the international specification (instead of a standard) which was released in 2013 as a key milestone. The specification was a critical first step toward developing an internationally agreed methodology. It provided guidance on questions like how do we draw the system boundaries – what is in, and what is out? Do we need to account for soil carbon? Do we need to take the use of a product into account, and consider the end of life disposal?

That ISO 14067 passed last year as a standard is of no surprise to Daniele. He remembers a letter from the UN just before work on the new standard began. It said that “developing a standard for carbon footprinting is of strategic importance” in achieving the aims of the UNFCCC, the international treaty on climate change that set national GHG reporting, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement in motion way back in 1992.

One of the most important aspects of the ISO 14067 new standard is that the life cycle approach is fully embedded, considering the entire product life from cradle to grave allows us to assess the true impact of products. Organisations won’t be able to hide the true impact of their products by only looking at one part of the life cycle. For example, the use phase for an energy-consuming product, or transport of raw materials to the manufacturing site needs to be accounted for.

Those fundamental methodologies have not changed in the recently published standard. The key difference is however that it is now an internationally agreed standard. A level playing field has been created. Previously, a number of competing for footprinting methodologies were used around the world, meaning apples-to-apples comparisons were not possible. This cuts down on misinformation which may arise when only one part of the life cycle is considered and communicated.

In my view, it’s extremely meaningful that Carbon Footprinting is covered in an ISO standard. It means each country had an equal voice throughout the development process ensuring it’s a fair standard. Over 50 nations were part of the process, including a great number of developing countries like Sri Lanka, Vietnam or Nepal and emerging countries like India or Brazil.

Partly funded by the Swedish Government I was part of a capacity-building programme for South and South-East Asian Countries. Providing some of my own time as well, we ran workshops and seminars to build knowledge and capacity around carbon footprinting, but most importantly also on the process of developing international standards. One great thing about ISO standards is that a vote or submission from Sri Lanka counts just as much as one from the US for example. All countries are encouraged to have a voice and their seat around the table. This is especially important as the economies of developing countries are often relying on exports of food products. With a current focus on our diet as a contributor to Climate Change, it is important that those countries had a say in developing a fair standard, and build up a capacity to undertake those calculations.

Carbon Footprinting Training in Bangkok with participants from Sri Lanka, Nepal, Cambodia and Vietnam

The same is, of course, true for New Zealand. However, we are fortunate enough to have the capacity in our country and MPI – back then MAF – funded a whole range of carbon footprinting studies for food products. This was at a time when food miles were big discussion points. The standard helps to shift the focus to include the full production system, whereby transport is not the only aspect to consider. Once all stages of growing and processing food are taken into account, it becomes a fair comparison and transport potentially plays a lesser role. This still depends on the type of food and the mode of transport of course.

Daniele and I agree that the standard is more relevant today than it ever was. The carbon footprint of products is what organisations need to know to calculate their Scope 3 emissions. With over 600 companies committed to setting a science-based target and over 100 companies in New Zealand in the Climate Leaders Coalition, there is a real need for robust calculations. One of the primary reasons for companies struggling with their science-based target approval is a lack of Scope 3 screening. The more products which have got a carbon footprint calculation, the easier it will be for organisations to calculate their Scope 3 emissions from their supply chain.

Daniele is based in Italy and has some more insight into developments in Europe. He expects that the continued adoption of product carbon footprints will be driven by the market in the next few years, but he doesn’t exclude the possibility that they become mandatory at some point in the future. The development of the Product Environmental Footprinting (PEF) guidelines from the EU’s ‘Single Market for Green Products initiative’ for example base the carbon part of their methodology on ISO 14067. This shows that it was even more important for New Zealand to contribute to this standard.

Leave a comment