Most people would agree that restoring and enhancing the waters of our wetlands, stream banks and shorelines is “A Good Thing” – places look nicer, bird and fish life come back and so on. But it costs money and takes time – much of it volunteer time. Do we only properly fund this important work when it’s obvious that the cost of doing nothing outweighs the cost of doing something? In a competitive funding environment, how can we justify more comprehensive, strategic and proactive investment in environmental restoration?

It’s been clear since at least the 1930s that economic indicators don’t measure everything that counts. In response to President Franklin D Roosevelt’s request for a simple indicator of recovery from the Great Depression, Professor Simon Kuznets suggested Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a measure of the churn of money through the economy. Although Kuznets warned at the time that it should never be used to indicate anything else, GDP became the default indicator of economic success.

From being a simple indicator, GDP has become a goal in itself: a goal that is defined only in terms of the movement of money. In mid-September New Zealand celebrated achieving 3.6% GDP growth1 in the June year – “one of the strongest growth rates in the developed world”.

Are we counting everything that counts?

But GDP does not and cannot define goals that many people endorse, for example, healthy, happy people and healthy built and natural environments. The perverse outcome is that environmental crises like oil spills make GDP look great, because it measures the money invested in emergency response and clean up while ignoring the costs of ecosystem harm and its local flow on effects on fishing, amenity, tourism and jobs. This is because the economy treats people and places as “externalities” – as being external to the business of commerce, with the result 2 that neither governments nor businesses “account for the damage their lawful activities inflict on nature and society.”

This escalating damage has led Nobel Prize-winning economists, accountants and scientists to conclude 3 that “we will continue to destroy the planet” “unless we value the goods and services currently provided by the natural world for free and factor them into the global economic system.”

In 1997, Robert Costanza and others 4 valued these natural ecosystem services (healthy air, water and soil; pollination and food to name but a few), which nature provides for free, at $US33 trillion a year. They recently revalued them 5 at $US125 trillion a year – while also estimating annual losses in the value of these services at $US4.3–20.2 trillion.

“The global biodiversity crisis is so severe that brilliant scientists, political leaders, eco-warriors and religious gurus can no longer save us from ourselves. The military are powerless. But there may be one last hope for life on earth: accountants.” – Jonathan Watts 6

Still contested by many who argue that nature is literally priceless, this approach to valuing nature by measuring natural capital and its stocks and flows, is nevertheless not only gaining ground but also identifying other overlooked values that can also be monetized – or at least for now, itemised.

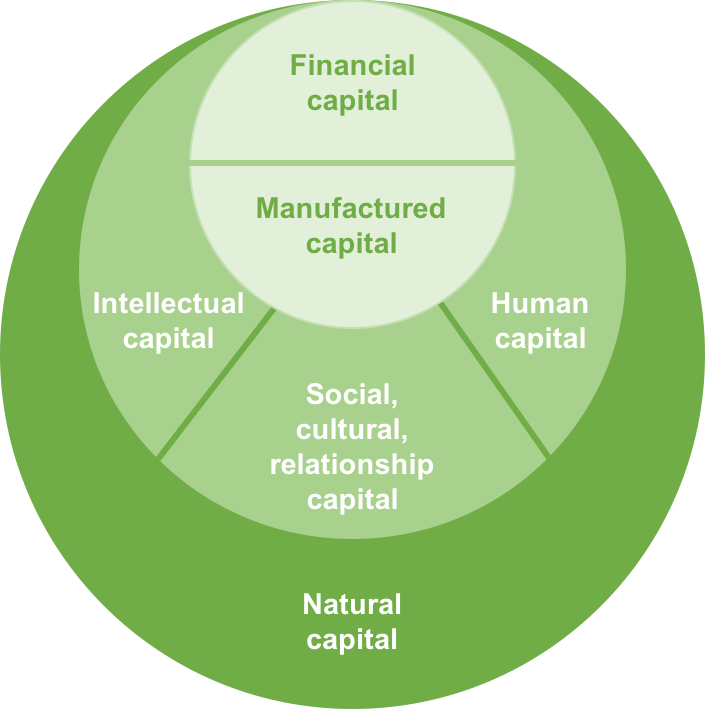

All six capitals are shown in the diagram below, which I’ve adapted from the International Integrated Reporting Council 7 by including cultural capital, which is significant for New Zealand and other colonised countries and accounts for the value of Māori commitment to the environment.

How would this model help iwi, communities, local and regional governments and sustainability staffers in businesses to win resources environment and sustainability work?

It’s basically an indicator competition. The current score is “GDP: 1 – All Other Indicators: 0”.

So monetising capitals other than financial can, for the time being, allow for genuine indicators of wellbeing to “compete with” GDP – or at least complement it.

After 30+ years of environmental management and training, one day in despair I said to a client, “Integrated catchment management is always funded to the point of failure – and never beyond.”

As a result, having evaluated many formal catchment management projects and informally observed several community projects doing this work, I see huge potential for the six capitals approach to attract long term funding that can really make a difference.

Riparian planting: plants ready to take to the Ngai Tahu stream.

Counting the change

I’m a great fan of the “measure to manage” school of thought, so let’s take a look at how a typical environmental restoration project might increase the value of the six capitals.

It starts with project design. Here’s an overview of how we’d design a project that measured the six capital gains.

The very first thing to do is gather together all the actors; iwi, community, technical, financial, social, engagement, monitoring and evaluation experts – and more. All these people will define the issues and opportunities as they see them, and agree on how they will work together 8,9.

After that, it’s QED – quod erat demonstrandum. Things always sound better in Latin! QED is said at the conclusion of a proof and means “what was to be demonstrated”. Sometimes (incorrectly) taken to mean “Quite Easily Done”, or, in other words, for a triumphantly conclusive proof, “Nyer nyer ny-nyer yner!”

Step 1: Quantify or Qualitatively describe the harm across the capitals: what are the community, business and insurance costs of floods, soil loss and sediment deposition on land or in water; of reduced fish catches and bird counts; or higher water treatment costs; or loss of recreational, cultural and amenity values? Clearly defining the ecosystem harm and its consequences for people helps to justify a project on the basis of both reducing the costs of harm and increasing the benefits of restoration and enhancement across the six capitals.

Step 2: Embed an understanding of the capitals into project planning, implementation, indicator development, monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

Step 3: Do the work, then measure the outcomes across the six capitals.

And the all-important Step 4: study your learnings, celebrate your success and spread the word. Most of all, demonstrate the returns on investment in your project reporting and funding applications, so you can carry on doing more and doing it better.

Scared to try? Don’t be. There is a long and growing list of environmental research and restoration projects in New Zealand that have measured some or even all of the six capitals.

We can pick up a toolbox full of tools from these examples, and catch the inspiration virus from them, too.

Defining and measuring the capital gains from restoring our waters

Below is a very basic overview of the six capitals and the capital gains we can expect from a restoration project aiming to improve our waters.

Natural capital comprises the stocks and flows across nature’s provisioning, regulating, habitat and cultural services1. Depending on the project’s motivating issue, we would expect to demonstrate higher capital values resulting from reduced frequency and severity of excessive flooding or pollution; improved biodiversity of endemic flora and fauna and higher recreational and commercial harvests. For example, in the Whaingaroa Harbour 10 by Raglan, whitebait started coming back up rural streams within 2-5 years of farmers planting their denuded banks.

Intellectual capital refers to education, training, skills, knowledge, ideas and intellectual property 7. Companies and communities taking part in environmental initiatives exchange knowledge and skills and co-develop local solutions, gaining intellectual capital that will add value to their future activities 2,11. A 2007 report 12 found that in the preceding 12 years the Whaingaroa Harbour Care project was estimated to have provided work and training opportunities for over 70 people through its nursery and tree-planting operations, and received training in plant propagation, seed collecting, native plant identification, weed and pest control, stormwater management, fencing, rehabilitation of whitebait spawning areas, construction of fish passes in culverts, deckhand skills (while boating plants across the harbour) and health and safety practices including chainsaw certificates and first aid certificates. The numbers will be significantly higher and the skills more diverse by now. Harbour Care itself has built considerable intellectual capital, to the extent that it is now mentoring other care groups about these skills and also with obtaining funding.

Social, cultural and relationship capital is a collective capital that lies in the connections and shared understandings among people, including first nations, which help them work together for common purposes (7, 2).

Fundraising for, helping with and benefiting from environmental restoration projects builds this intangible but vital capital that benefits direct participants as well as the wider community by delivering a more strongly bonded community. A 2010 review of Project Twin Streams 11 estimated it delivered at least 21,549 hours of community education. The project recorded 84,278 hours of volunteer time, being 48,434 hours of weeding and 35,844 hours of planting – the lasting benefit to community cohesion shown by reduced littering and vandalism. The project included a strong cultural component, where tangata whenua used traditional Māori practices to educate and connect Māori and all members of the community to the land and waters. The project coordinators reported the positive effect that had on young urban Māori and the sense of pride it gave them.

Human capital is an individual capital that accrues to project participants. Seen as vital for sustainable development, it includes (7) leadership, joy, passion, empathy and spirituality.

In longer term projects, local volunteers have the opportunity to become paid coordinators of community restoration efforts, and from there into other paid work. Additional skills 12 include newsletter production, leadership, administration, advocacy, communication and life-skills. In the Whaingaroa, many people, including some ex-convicts, gained employment using their skills as fencing contractors, while local flax weavers were able to harvest plantings and sell their products through the local shops and eco-tourism operators created new businesses including motels. Several people have moved on to provide expertise to other government and community restoration projects.

Other benefits noted in four projects reviewed (10, 11) were enhanced youth development outcomes and school attendance, educational opportunities through new environment-related school programmes and vocational training, and increased viability of Māori traditional medication through the protection and propagation of rongoa plants.

Manufactured capital, sometimes called produced capital, comprises built physical objects used to produce goods or provide services, including buildings, equipment and infrastructure such as roads, ports, bridges and stormwater, water supply and wastewater systems (11). Many environmental restoration projects develop new manufactured capital in the form of walkways, cycle ways, bridges, bird-watching hides, interpretive signage, plant nurseries, fencing, park benches, art works, play spaces and more. All these contribute to the enjoyment of local communities and visitors.

Financial capital relates to monetary stocks and flows in the usual sense, as well as fiscal multipliers. One US study 13 estimated that when public money from taxpayers and ratepayers is invested into environmental restoration projects, 10.4 to 39.7 green jobs are created for every $US 1 million invested, compared with the oil and gas industry, which supports about 5.3 jobs per $US 1 million invested.

Local plant nurseries set up to support environmental restoration projects are a common example of financial capital gain. These often go on to be successful businesses that create new jobs by employing local people to help meet the planting needs of farmers, councils, park managers, home owners and more. Some projects also generate increased income from increased passive recreation and tourism. Whaingaroa Harbour Care has set up a native plant nursery and offers a farmSMART service to help farmers with plantings. Four similar nursery business were set up as a result of Project Twin Streams (11).

Farmers say riparian planting and retirement of adjacent land is expensive – but so is losing even one cattle beast a year by getting bogged down in an unfenced stream, not to mention the costs of annual “drain” clearance necessitated by sedimentation and stream bank collapse.

In sum, environment and sustainability initiatives deliver significant gains across all six capitals – if we take the trouble to measure them.

I find the fiscal multiplier particularly interesting as an indicator of the return on investment from public, private, nonprofit or business sources.

Green jobs and the restoration economy

The benefits to human health and wellbeing of a healthy natural environment are moving into the spotlight just as government austerity measures are losing ground as governments increasingly recognize the much wider beneficial effects of economic stimuli.

Tellingly, macroeconomist Josh Bivens investigated the employment effects of the December 2011 US law approving environmental regulations to reduce emissions of mercury, arsenic and other toxic metals 14. It was estimated to prevent up to 11,000 premature deaths each year and deliver many other health benefits, but pre-passage, a lot of people were concerned it would “kill jobs”. When Bivens investigated it in detail 15 he found that far from killing jobs, the “toxics rule” could create over 100,000 jobs in the US by 2015. Bivens’ message is “going green won’t kill jobs during hard times”: when the economy is doing well, environmental regulation has no effect on job growth; but when it isn’t, such regulation is very likely to create jobs. These days, we need more jobs – and green jobs most of all.

Globally, the transition to a “green economy” could yield 15-60 million jobs by between 2012 and 2032, according to the International Labour Organisation 16, lifting tens of millions of workers out of poverty while improving social and environmental outcomes – and decarbonising the economy.

It’s clear from the literature that New Zealand has the skill base to assess the benefits of environmental initiatives across all six capitals, and the tools are getting better all the time.

In July 2016 the Natural Capital Coalition launched the Natural Capital Protocol, a standardized framework that helps business measure and value natural capital, to help them benefit from understanding their relationships with nature 17.

We can expect similar tools to emerge to help standardise and promote the measurement of manufactured, intellectual, social, cultural, relationship and human capital, too.

For iwi, communities, nonprofits and government bodies, measuring the very real benefits of environment and sustainability initiatives across the six capitals could help them attract more funding that demonstrates the wide extent of the return on investment.

For businesses, such indicators could open up ways of better valuing their key assets – people and the environment – by measuring the effects of how they work across all six capitals. This would include staff, customers and suppliers and the whole life cycle of goods and services all along the supply chain back to the natural stocks and flows upon which they draw. This would inform their reporting in terms of the GRI, or Global Reporting Initiative 18, for example, and enable them to list on the growing number of stock exchanges around the world that are requiring their listed companies to provide integrated reports that address ecologically and socially as well as fiscally responsible management.

To sum up, environmental work grows much-needed green jobs in the already significant and rapidly growing “restoration economy” 19 and helps us redefine who and what “the economy” is for.

If we take this wider view of the financial benefits of our work, what could follow?

- How much more funding could our public bodies attract for their environment and sustainability work?

- How many other sources of funds would open up to us?

- How many more restoration projects could we do?

- How could we make the case for funding the transition to a low carbon economy – regardless of what people think about climate change?

- How many different social and ecologically responsible initiatives could we undertake, as iwi, communities, governments, nonprofits and businesses?

Let’s start counting what counts.

References cited

Jamie Gray (2016) Construction and exports drive growth. An article in the New Zealand Herald of 16 September 2016. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=11710248

2. Jane Gleeson-White (2015) Six Capitals, – or can accountants save the planet? Rethinking capitalism for the twenty-first century. W.W. Norton Publishers, New York, London (p xv). https://janegleesonwhite.com/six-capitals/

3. Pavan Sukdev (2010) Global Biodiversity Outlook 3. United Nations Report. https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/gbo/gbo3-final-en.pdf

4. Robert Costanza, Ralph d’Arge, Rudolf de Groot, Stephen Farber, Monica Grasso, Bruce Hannon, Karin Limburg, Shahid Naeem, Robert V. O’Neill, Jose Paruelo, Robert G. Raskin, Paul Sutton, Marjan van den Belt (1987) The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, May 15, 1987. VOL 387, p253. http://www.esd.ornl.gov/benefits_conference/nature_paper.pdf

5. Robert Costanza, Rudolf de Groot, Paul Sutton, Sander van der Ploeg, Sharolyn J. Anderson, Ida Kubiszewski, Stephen Farber, R. Kerry Turner (2014) Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change. Vol 26 (2014) 152–158. http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/article-costanza-et-al.pdf

6. Jonathan Watts (2010) Are accountants the last hope for the world’s ecosystems? An article in The Guardian, October 29 2010. Cited in (2) above. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/oct/28/accountants-hope-ecosystems

7. IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Council). 2013. Capitals Background Paper for <IR>. March 2013. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IR-Background-Paper-Capitals.pdf

8. Les Robinson (2013) Changeology: how to enable individuals, groups, and communities to do things they’ve never done before. Scribe Publications, Australia. https://scribepublications.com.au/books-authors/books/changeology

9. Clare Feeney (2013) How to Change the World – a practical guide to successful environmental training programs. Global Professional Publishing UK (now Stylus). http://www.clarefeeney.com/products/for-sale/

10. Whaingaroa Harbour Care: http://www.harbourcare.co.nz/

11. Morrison Low (2010) Value Case for Project Twin Streams. A report prepared for Waitakere City Council – October 2010. Ref: 176103. No longer available online. See http://www.morrisonlow.com/

12. Buchan, D (2007) Not Just Trees in the Ground: The Social and Economic Benefits of Community-led Conservation Projects. WWF-New Zealand, Wellington. http://www.harbourcare.co.nz/wp-content/files/wwfnz_not_just_trees_in_the_ground.pdf

13. Logan Yonavjak (2014) Now THIS Is What We Call Green Jobs: The Restoration Industry ‘Restores’ The Environment And The Economy. An article at http://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2014/01/08/now-this-is-what-we-call-green-jobs-the-restoration-industry-restores-the-environment-and-the-economy/. See also Todd K. BenDor, T. William Lester, Avery Livengood, Adam Davis and Logan Yonavjak (2013) Exploring and Understanding the Restoration Economy. Downloadable from https://curs.unc.edu/files/2014/01/RestorationEconomy.pdf

14. Josh Bivens (2012) Going green won’t kill jobs during hard times. New Scientist Issue 2857, 24 March 2012. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21328576-500-going-green-wont-kill-jobs-during-hard-times/

15. Josh Bivens (2012) The ‘Toxics Rule’ and jobs – the job-creation potential of the EPA’s new rule on toxic power-plant emissions. Issue Brief #325 of the Economic Policy Institute, a non-partisan think tank in Washington DC, February 17 2012. Downloadable from http://www.epi.org/publication/ib325-epa-toxics-rule-job-creation/

16. ILO/UNEP (2012) Working towards sustainable development: Opportunities for decent work and social inclusion in a green economy. A joint ILO/UNEP study published on 12 June 2012 by the Green Jobs Initiative, a partnership between the United Nations Environment Programme(UNEP), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Organization of Employers (IOE) and the International Trade Union Congress (ITUC). The report is downloadable from http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/ilo-bookstore/order-online/books/WCMS_181836/lang–en/index.htm

17. Natural Capital Protocol: a standardized framework that helps business measure and value natural capital, to help them benefit from understanding their relationships with nature. http://naturalcapitalcoalition.org/protocol/.

18. Global Reporting Initiative: is an international independent organization that helps businesses, governments and other organizations understand and communicate the impact of business on critical sustainability issues such as climate change, human rights, corruption and many others. https://www.globalreporting.org/Pages/default.aspx

19. Storm Cunningham (2002) The restoration economy: the greatest new growth frontier. Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc., San Francisco. http://www.stormcunningham.com/

Clare Feeney is the sustainability strategist. She helps companies and governments solve environmental problems with targeted training programs. She is a published author and her book is called How to Change the World – a practical guide to successful environmental training programs. Find out more at http://www.clarefeeney.com.

Leave a comment