There is still some confusion over the health of the bee population in New Zealand. Some argue that bee populations are stable or increasing, while others suggest that bee populations are rapidly declining.

The short answer is that wild bee populations are declining, and while managed hive numbers are increasing, honey yield isn’t. This is a clear example of diminishing returns (increased inputs, but no significant increase in outputs).

Wild bee populations are declining at a frightening rate due to a phenomenon called Colony Collapse Disorder and there’s reason to be alarmed. The plight of the bees would undoubtedly have a disastrous impact on human life and our food sources.

Our diets would suffer tremendously and the cost of certain products would surge because bees pollinate a significant amount of our planet’s agriculture. The California Almond Board stated that without bees, almonds “simply wouldn’t exist and coffee would become expensive and rare”.

Bees have always been a vital part of agriculture, and although hive numbers of European honey bees are increasing in New Zealand (due primarily to a growing export market for Manuka honey)…the decline in feral honey bees, and the Bumblebee, is causing concern within the scientific community.

So why are wild bee populations suffering Colony Collapse?

Three major reasons to consider are Pesticides, habitat loss, and the Varroa mite.

According to an 18-year study of 62 wild bee species, there’s an indisputable link between shrinking bee populations and the use of neonicotinoid pesticides. Ecological Entomologist Ben Woodcock says the research indicates the full scale for the problem. “Prior to this, people had an idea that something might be happening, but no-one had an idea of the scale. Our results show that it’s long-term, it’s large scale, and it’s many more species than we knew about before.”

Deforestation and habitat loss affects wild bees more than cultivated honey bees, which are kept relatively safe in managed hives. Likewise farmed bees have a greater chance of surviving the ravages of the varroa mite courtesy of human intervention. Feral bee populations theoretically shouldn’t be able to last more than a couple of years in the wild before varroa destroys them, but studies show colonies surviving over several years. Dr Mark Goodwin, from Plant and Forest Research’s apiculture and pollination team, says this may be due to a natural resistance to varroa, “or that the feral colonies are living in a way that confers resistance – possibly making their nests in a tree that contained a natural deterrent to the mite.”

Luckily the high price and global demand for Manuka honey have driven an expansion of beekeeping in New Zealand, and an increase in hive numbers. However, that doesn’t mean kiwi bees are out of the woods.

The New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries 2016 report on Apiculture shows there are still reasons for similar concern in New Zealand. Honey yields are dropping despite large increases in the number of hives. The 2015/16 season produced an estimated honey crop of 19,885 tonnes, a record crop but only slightly higher than the previous year despite an additional 108,174 hives.

The importance of bees to NZ.

Without bees, our major agricultural export industries (worth over $5 billion) would be in severe trouble.

Luckily there are several businesses and collaborations facilitating sustainable organic agricultural industry growth.

An initiative between Ceres Organics and BeezThingz to help bring bees back to Auckland has resulted in the installation of six hives at the Ceres Mt Wellington office. “We will be providing jars of honey for our staff to enjoy,” says Ceres Organics bee project manager, Dominic Leverton.

Thirteen schools around Auckland and other like-minded businesses (Langham Hotel, TVNZ) are also working with BeezThingz on the City Bee Initiative to make Auckland the most bee-friendly city in the world. “People find that their fruit trees all of a sudden flourish when there are bees around and the whole garden comes to life,” says Managing Director of BeezThingz, Julian McCurdy.

The New Zealand Manuka honey industry is a sound example of agricultural diversity in horticulture while providing economic benefits. The honey industry earns $242 million in exports a year, of which Manukamakes up about 80%. A target has been set of $1.2 billion export revenue for Manuka honey alone, by 2028.

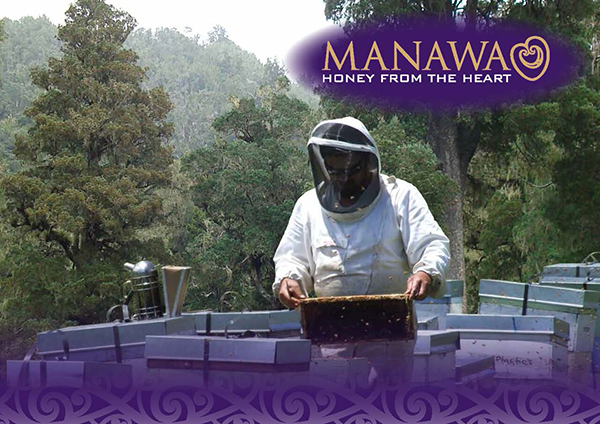

New Zealand Maori producer Manawa Honey, is marketing ‘hive to jar’ and from ‘land to brand.’ The single source for their honey products derives from the Te Urewera region (a vast region over 200,000 hectares of remote native forest). Being identified as a single source brand creates a premium, high-value honey.

Brenda Tahi, CEO of Manawa Honey sees the restoration of Te Urewera forest as a fundamental part of their business model.

“We are responsible for about 9,000ha of indigenous forest, and run programmes to restore our forest ecosystems,” said Brenda. “Honey production brings the honey bee back into the forests where it has been a part of the ecosystem for over 150 years. We see the honey bee as a valuable pollinator where the numbers of traditional pollinators, especially birds and bats, are depleting from the impacts of introduced pests such as stoats and possums.”

ManawaHoney uses their business as a stepping-stone to regenerative forest and land-use management. The business is currently involved in a project with the Tuhoe Tuawhenua trust, to protect native species while tracking the health of their forest ecosystem and community well-being. Many local communities and indigenous people still rely heavily on native flora and fauna as part of their daily lives and are understandably concerned about environmental health.

However, land conversion, the separation of production and consumption, rural-urban migration, and exotic/alien species have affected how local knowledge is passed from one generation to the next.

Fortunately, Manawa Honey takes an Iwi approach to every aspect of their business. The ‘iwi’ approach encourages a generational and holistic business model, to ensure that the extensive knowledge of the Maori over their 730 years of settlement in New Zealand is passed on. “Our honey production is integrated with our forest ecosystems management and is part of our overall strategy to lift the well-being and resilience of our people, our forests and environment into New Zealand’s future, “ explained Brenda.

A small Northland honey business making its mark is Happy Beekeeping Limited (HBK Ltd), founded by Issac Flitta. Initially working in Auckland as a product design consultant, he was given a brief to create a new type of eco- friendly beehive. In the process, Flitta fell for the “little stripy fellas”, escaped the city and shifted to Northland to learn the craft of beekeeping and create his own brand of honey.

When asked his advice for young Kiwis interested in organic farming, Flitta responded:

“Never assume success is attached to an indoor office job. New Zealand’s greatest business opportunity lies in the production of organic produce.”

Organic agriculture is great for business, with consumer demand for organic and pesticide-free food showing double-digit growth. Organic is also better for honey bees with organic farms supporting 50% more pollinator species than conventional farms.

Although BeezThingz, Ceres Organics, Manawa Honey, and Happy Beekeeping are doing great work for our biodiversity and the economy, bees are still under threat and studies prove a decline in sources of pollen and nectar. Add the long-term effects of Varroa mite and other diseases and the health of our bees becomes a critical issue. The disappearance of cultivated bees, or even a substantial drop in their population, would make many foods scarce and expensive. Humanity may survive—but our meals would be a lot less interesting.

Leave a comment