The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) spoke firmly: the UK should legislate as soon as possible for a net zero economy by 2050. When the target is set in concrete, it’ll be, by some distance, the most purposeful climate commitment in the industrialised world. Those who don’t think our Zero Carbon Bill goes far enough — and those that do — should take note.

If you hadn’t heard of net zero, you have now. The turning off of the greenhouse gas emissions tap is finally receiving the media attention it’s been so desperately waiting for. In the UK, the environment has just edged past immigration in a survey of public concerns. In Australia, a poll of more than 100,000 voters found that the environment was issue number one for most respondents. Forget the lemmings-off-a-cliff UN reports or the effects of climate change, thank the confluence of young and old — and the glue of a rebellion.

Banksy pays tribute to Extinction Rebellion

Greta Thunberg, Sir David Attenborough and Banksy have all played their part in the UK. But it’s been the eyebrow glueing tactics and overton-window-moving toil of Extinction Rebellion that’s been getting people talking over their garden fences. Extinction Rebellion’s demand of net zero by 2025 is patently absurd. But their media-grabbing tactics haven’t been about a date, they’ve been about a target. And a level of government commitment to honour that target.

Net Zero

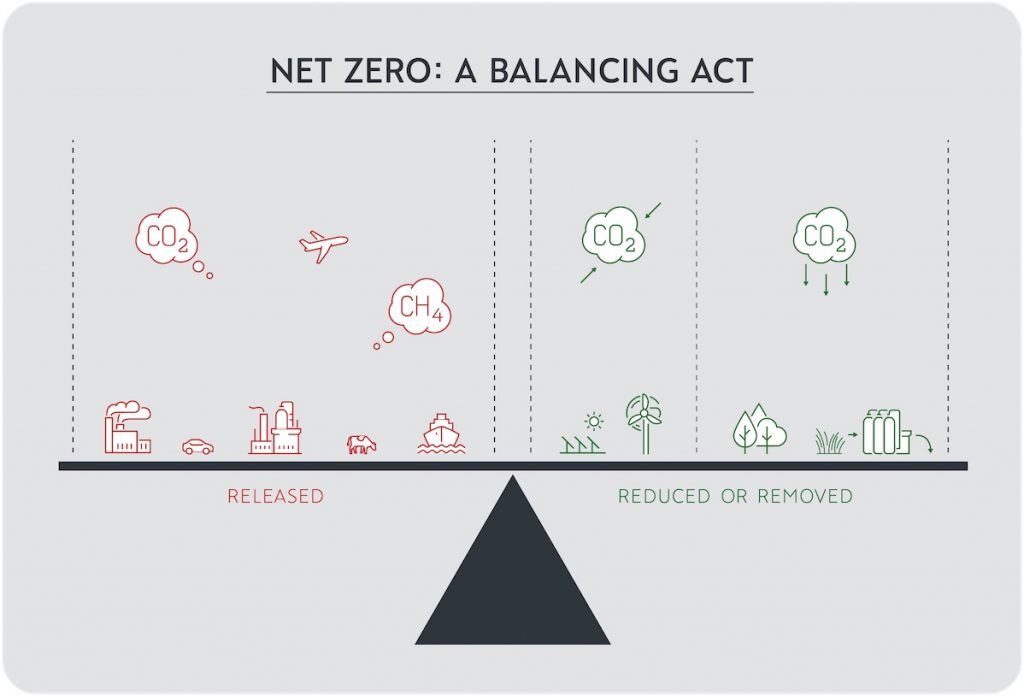

Net zero is achieved when a country, city or organisation’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) are balanced by the drawdown of an equivalent amount from the atmosphere. So the GHGs emitted by cars, industry and cows must be counteracted by the GHGs removed from the air — for example by the planting of new forests, restoring wetlands, implementing regenerative farming techniques or through carbon capture technologies, which bury carbon dioxide underground.

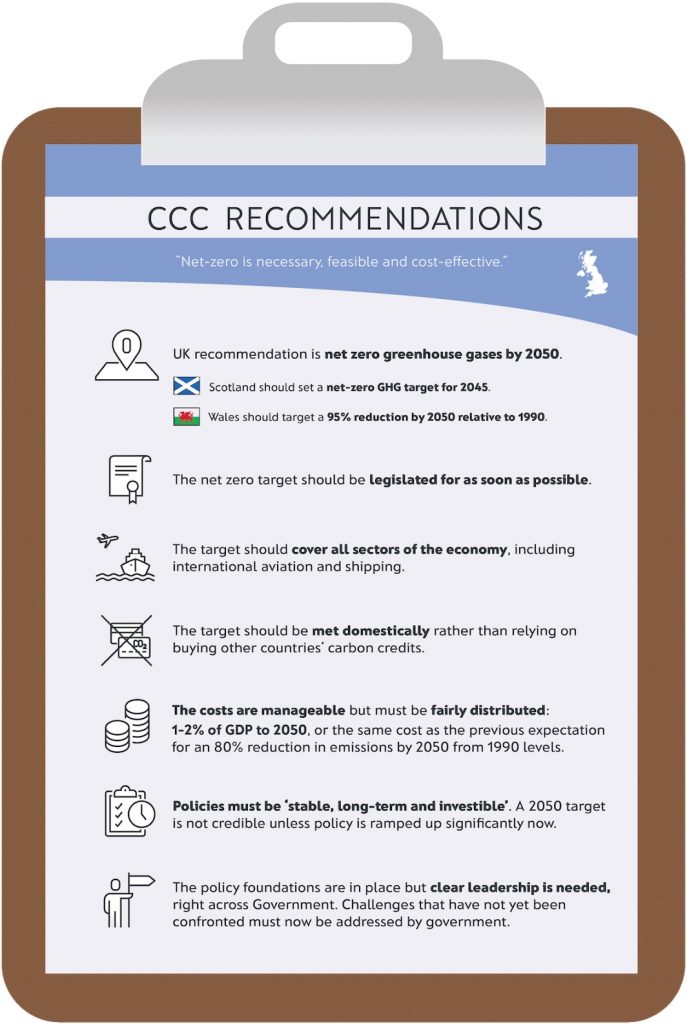

If net zero by 2025 is absurd, net zero by 2050 is ambitious. It’s also ‘necessary, feasible and cost-effective’ says the CCC, the UK’s team of expert advisors and watchdog on everything climate change. If you missed it, this month the CCC recommended a target that is so without caveats, it’d put the UK “at the top of the pile” relative to other international net-zero goals.

The CCC’s recommendations

Created by John Lang from ‘Net Zero – The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming’

Domestic politics allowing, the UK is in a summer race with France (and now Germany) to join Norway, Sweden, Denmark, California and Catalonia as the biggest global economies committed to net zero by 2050. The UK target will be later than Norway (2030) and Sweden (2045), but miles more meaningful. Jam-packed with accounting and environmental integrity, the advice — if taken up in full — will not allow international offsets, will include international aviation and shipping and bake in no special dispensation for hard-to-abate sectors like agriculture, aviation and heavy industry. In the midst of Brexit, the Brits are about to agree on something much bigger than their relationship with Europe: the net zero gold standard.

Sure, but what’s in there for New Zealand?

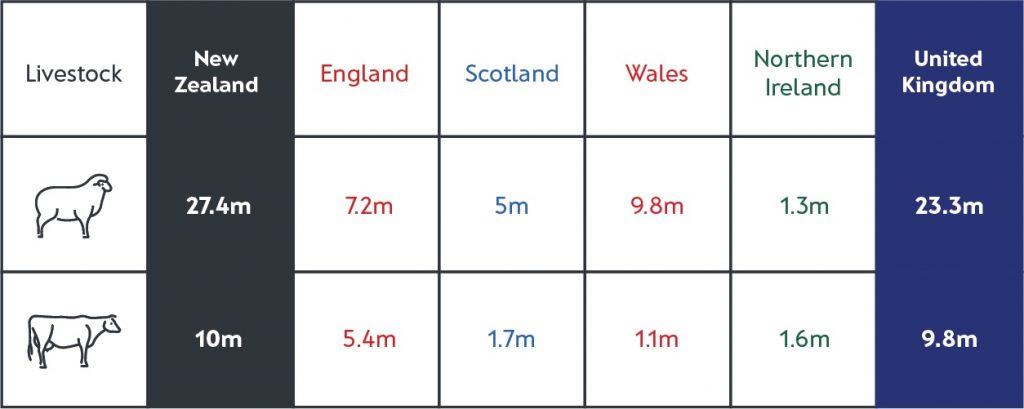

An economy 13 times bigger than New Zealand’s (and one with plenty of ruminant animals) is about to lead the world into the biggest economic transition ever. The Zero Carbon Bill and NZ policymakers should take the CCC’s advice and its response as reassurance about the long-term political power of institutions, the value of patient politics (but urgent policy), evidence-backed ambition and the imperative of bold climate leadership in an ambiguous world.

1. An economically prudent, equity conscious and evidence-obsessed independent advisor is indispensable

The CCC’s advice set a blueprint for the UK’s net-zero transition. In doing so, it has also set a blueprint for how NZ’s future Climate Change Commission (‘Climate Commission’) should operate — with scientific, economic and social credibility. It’s why the CCC’s advice has always been taken up: it doesn’t shy away from crunching the anticipated economic costs of the advice it’s dishing out, and crucially, how those costs might be distributed evenly across society. So, the CCC doesn’t just pay lip service to the ‘just transition’ — the just transition is part and parcel of their advice.

The CCC is also candid about the costs of inaction: “Set against the costs, there will be significant benefits, including avoided costs”. These include savings from electrifying surface transport as early as practicable, the benefits accruing to human health, air and water quality, enhanced biodiversity and increased resilience to climate change. All in all:

“These would partially or possibly even fully offset the resource costs [the CCC] estimated i.e. up to 1-2% of GDP in 2050.”

In response to the Zero Carbon Bill that’s finally heading through NZ parliament, Greenpeace NZ chief Russel Norman warned it won’t enforce the targets it stipulates. But perfect policy should not be the enemy of better policy. Accountability will come, not through an Act of Parliament, but through fostering our nascent new institutions: our soon-to-be Climate Commission and the five-yearly ‘emissions budgets’ it will set for governments.

Because policy success on climate change action will, sooner than we all think, rival policy success on the economy, successive governments will one day be defined by how they meet emissions reduction budgets — as recommended by our Climate Commission. New social norms follow new institutional norms like a pack of hounds to a scent. I’m just going to throw it out there: National and Labour will lose future elections over climate change. This thing is, after all, just warming up.

2. National nonpartisanship

Cross-party agreement in NZ has slowly emerged but nothing’s guaranteed until, as James Shaw says, “the ink is dry”.

Twelve years back, the UK passed their Climate Change Act — 463 MPs voted for it; three against it. David Cameron’s conservative rebrand explained the landslide, still, the way UK right-of-the-aisle MPs actually take climate change seriously is seriously impressive. The Climate Minister Claire Perry immediately welcomed the CCC advice:

“Since 2016 we’ve been clear that we will legislate for a net zero emissions target, and I hope we will become the first major economy to do so.”

Perry’s boss Greg Clark, the Secretary for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, described the advice as a “seminal” moment in the UK’s low-carbon transition. The UK tabloids came out flashing, naturally, but the political and media response was overwhelmingly a choir of support.

In NZ, National has begrudgingly come around to James Shaw’s expert diplomacy and primal persistence. But their “unusually nonpartisan” cooperation has, I think, just as much to do with the fact that the deniers in their ranks have finally moved on, both from the party and their archaic arguments. It’s called the affective tipping point: when the scientific evidence of something (and the economic benefits of doing something about that something) piles up so colossally, even the most ardent denier finds the reputational consequences of clinging on to what they’d like to think too much to bear. May it continue.

3. (Agricultural) Ambition is not pie in the sky

The CCC admits this transition is going to be tough. But from farming to industry to aviation, the hard-to-abate sectors were not let off the hook. Wales gets a little extra time to take care of its methane emissions (a 95% reduction of all GHGs against its 1990 baseline by 2050) but the rest of the Kingdom does not.

Created by John Lang from data collected by the UK and NZ governments.

The share of the UK’s carbon profile attributed to agriculture is due to head north from 10% to 33% over the next three decades. Rather than cry foul, key stakeholders are readying themselves for the challenge. Their influential National Farmers Union surprised everyone, possibly even themselves, by committing to a more ambitious date of net zero emissions than the CCC has now suggested.

“[We] should go net zero by 2040 or earlier to stay ahead of the competition in the global food and agriculture market.” [NZ, take note]

Then there’s Meat and Livestock Australia across the ditch: 2030. And New Zealand’s largest state-owned farming group, Landcorp: 2025 (carbon neutrality will have them planting 10 million native trees).

Then there’s Federated Farmers: never. Spokesperson and vice-chairman, Andrew Hoggard:

“This decision [to reduce methane emissions by 10% to 2030 and between 24-47% to 2050] is frustratingly cruel, because there is nothing I can do on my farm today that will give me the confidence I can ever achieve these targets.”

Err — the Biological Emissions Reference Group (BERG) has already found that current and available mitigation options (mainly farm management practices) could get NZ a 10% reduction in absolute biological emissions. Similarly, the NZ Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre found a high confidence that technology — methane inhibitors and vaccines — can deliver a 30-50% reduction by 2050.

Even if some in the New Zealand agricultural community can’t get their heads out from between the fence, we will meet those targets. With technology, world-leading on-farm management practices and our economically prudent, equity conscious and evidence-obsessed Climate Commission firmly in place, by 2030, we’ll almost certainly up them. Come 2050, we’ll beat them.

4. Global leadership is needed now

Despite accounting for only 1% of global emissions today, the legacy of the industrial revolution means the Brits have long been one of the top five cumulative contributors to climate change. NZ is more a current contributor — per capita, we contribute double that of the Brits. And before someone says it, if we were to add up all the countries with ‘bugger all emissions’ they’d make up about one-third of global emissions.

The Paris Agreement requires rich nations to meet their ‘highest possible ambition’ under its objective to hold global temperatures ‘well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the rise to 1.5°C’. As such, the UK’s CCC agreed net zero by 2050 was its ‘appropriate contribution’ due to: the UK’s ‘capability to go further’; it’s historical responsibility for climate change; its strong and widely-respected policy-making institutions; its leading role in low-carbon technology and climate finance; and in light of recent international science, namely the IPCC report on 1.5°C.

Aotearoa New Zealand is also aiming to go net zero (bar methane) by 2050. Should we be? We’ve also got the capability to go further, we have some of the strongest decision-making institutions in the world, we are a renewable energy powerhouse, we’ve got the world’s most innovative and efficient farmers, we’ve got marginal land we can plant with forest, we’ve got to keep on top of that clean, green image of ours, we’re usually up for a challenge… and, just Iike the UK, we’re in the deeply privileged position where we can see the world tomorrow and act on that world today.

New Zealand and the UK are dual participants in the High Ambition Coalition and Carbon Neutrality Coalition for good reason. By default, New Zealand’s Zero Carbon Bill is in coalition with the UK’s Climate Change Act because it was modelled directly upon it. In 2019, the UK and New Zealand must, in coalition and with France, Germany and Europe, legislate to ‘send a strong international signal at a critical time’. Just as the CCC advice concluded.

Created by John Lang for the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit: Net Zero Scorecard

In part two and three of ‘A Nod to NZ’, I’ll assess what the UK CCC has advised for land use and transport — the two sectors where emissions have either been flat or creeping steadily north (in both the UK and NZ). To even entertain the thought of net zero by 2050, both sectors’ emissions curves must be pointing downwards by 2030, and dropping vertiginously by 2040.

Leave a comment