“Environmental efforts that look to make things less bad will ultimately fail, because less bad is not good enough.” This was just one of world renowned Professor Michael Braungart’s thought-provoking judgements of current sustainability initiatives during his recent visit to New Zealand.

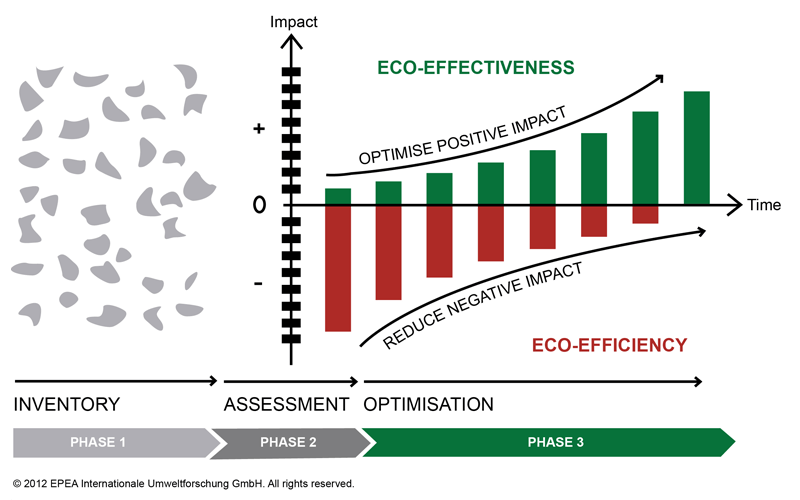

Prof Braungart is a Chemist, award-winning book author, co-founder of the Cradle to Cradle® design concept and CEO of the Environmental Protection Encouragement Agency (EPEA). The Cradle to Cradle® approach is inspired by nature, in which products, processes and systems operate without waste in an ideal circular economy. Conventional recycling and the concept of eco-efficiency are replaced by designing for abundance and the concept of eco-effectiveness – shifting the mindset towards doing the right things, rather than doing the wrong things perfectly. All waste materials in an old product become the “food” for a new product, either biological or technical.

I was fortunate to spend a couple of days with Prof Braungart during his recent visit to New Zealand. His presentation at our “Cradle to Cradle® and sustainable design” event for industry marked the start of a strategic partnership between EPEA and thinkstep Australasia. It was filled with sceptical observations, best practice examples and constructive ideas, delivered in Braungart’s typical witty style.

Here are my key takes on how the globally acclaimed Cradle to Cradle® concept could work for New Zealand and our local businesses.

Doing things perfectly wrong

Globally, many sustainability initiatives come from a good place but fail to achieve their potential because they are based on misconceptions. That happens because we’re employing the wrong approach. “If we make the wrong things perfect, we get them perfectly wrong” says Braungart. It’s one of my favourite quotes of his and it encapsulates the fact we’re asking the wrong questions. Too often we undertake measures in one area that compromise or subvert things we are doing elsewhere.

Europe has set aside large amounts of land for renewable energy and yet it continues to import huge amounts of corn and soy to feed farm animals. This takes up land in other countries and often contributes to significant losses of topsoil.

Using palm oil as a fuel is a further example. Europe imports 3m tonnes of palm oil to make biodiesel, when we know that one hectare of rainforest has 7000 tonnes of carbon in it whereas one hectare of palm plantation contains 60 tonnes of carbon. The problem is not that they are trying to encourage more environmentally suitable fuels but that the basis for the solution, palm oil, is the wrong thing to be using in the first place.

Sheep are not designed to be red wine resistant

Prof Braungart talked about a so-called wool carpet from a big Scandinavian company. The key misunderstanding was that the product is not really a wool carpet, but a Teflon carpet with some wool in it – because people want their carpets to keep looking good and sheep were not designed to be red wine resistant. When you try to make a natural material do a job that it cannot achieve naturally, you need a lot of chemical interference to make it perform the way you want.

Learning from cherry trees and termites

“We need to learn to become native to this planet and celebrate life. And we need to learn to behave in that manner.” – Braungart

Traditionally we take, make and waste in the form of landfill. Even if we include one or more loops of recycling, we ultimately discard a valuable material. This remains a one-way cradle to grave design approach.

We could, Prof Braungart says, learn a lot from cherry trees and termites. Cherry trees are entirely made of material that is beneficial to nature. The tree makes a few cherries and many thousand blossoms and they are all designed to revert to a biological system. Instead of being toxic and dangerous, everything it makes, uses and discards is actually nutritious to the planet.

Ants and termites live on this planet in abundant numbers – they vastly outnumber humans by a number of magnitudes – but they don’t cause problems because they produce nutrients and not waste. Why shouldn’t we be able to do the same? The actual number of people on Earth is less relevant than what those 8 billion people are doing to themselves and to the planet as they live.

The technosphere and the biosphere

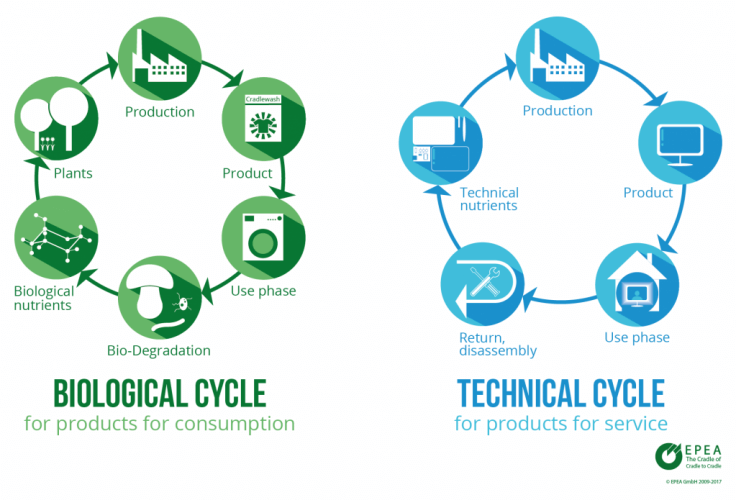

Cradle to Cradle® divides products into two spheres: technical and biological. On the technical side we have materials such as metals that can be used forever, for chairs for example or for washing machines. On the biological side, we have products that dissolve back into nature like cosmetics or natural fibre textiles. Using great design to make products that are technosphere or biosphere compatible, in much the same way that cherry trees and ants are compatible, will make the very concept of waste obsolete.

Maersk Line has already designed huge container ships that will not contain a single gram of waste. By identifying each nut and bolt of these 60,000 tonne ships, it will be possible to sort and reuse every aspect of the ship once it reaches the end of its working life. Mobile phones are another example of where we need to rethink waste. Right now they contain more than 40 elements of which only 9 are recycled.

Stop talking about waste

Human beings are the only species that create waste, says Prof Braungart. We need to turn that around by thinking of ourselves as native to this planet. When we focus on things like “zero waste” or circular economy, our headspace remains in waste, he says. What we should be doing is focusing instead on materials that can be used in the biosphere or the technosphere. Divide everything into biological nutrients and technical nutrients and design products that will take us forward that way. In Braungart’s words, “all waste is food.”

Opportunities for New Zealand

How can companies here in New Zealand think about and apply these concepts? We need change our conceptual understanding of how we make products and deliver services. Prof Braungart summarises it as “remaking the way we make things”.

Take New Zealand’s printing industry in as an example. If we wanted to encourage this sector to become a Cradle to Cradle® industry, we need to stop talking about the nasty chemicals that printers will (hopefully) not be using in the future, and instead focus on compiling a comprehensive list of positive chemicals that would enable printers to achieve the same results without causing any harm. “If I tell you there is no chicken in your dinner, it doesn’t really help you. You still don’t know what you’re eating.” The same principle applies to materials used in industry processes.

Steel as a service

Speaking of the steel industry, Braungart suggested that if we really want to produce steel that is compatible with the technosphere, then we need to completely change our view of what steel production means. This could be selling ‘steel as service’ i.e. leasing the steel for a purpose, with the steel mill maintaining ownership of the materials. It is thought that this would provide financial incentive for the production of new high-grade building steel which the mill would then reuse or recycle rather than downcycle into lower-grade steel products.

As more and more raw materials are used in a take-make-waste scenario, we are running out of materials needed to make new products. We already use more resources each year than the earth can regenerate. Damaging practices don’t become positive just because we do them less; they just serve to delay the inevitable.

Moving on from guilt management

Acting responsibly is not about doing less bad – because that really only amounts to “guilt management” – it’s about finding and creating bold ways to do more good. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a good start because it helps companies to minimise the negative impacts of what they produce. But to be effective, they need to focus on the positive, and this is where Cradle to Cradle® provides a path to redefine the very ways they do business.

Products need to be made and consumed in ways that mean, at the end of their lives, they can flow back into biological or technical cycles. Making things completely differently would change many of the conversations New Zealand businesses are having right now.

At the moment, New Zealand is still focused on guilt management – reducing, avoiding, minimising – based on ethical concerns. If we turn that around, and leverage 40 years of blame and shame to start inspiring companies to think in new ways, a new era can begin.

Cradle to Cradle® needs collaboration

Creative innovation, an optimistic approach, reliable data and global collaboration are the catalysts needed for Cradle to Cradle approaches. To facilitate such a step change thinkstep collaborates with Prof. Braungart’s institute EPEA in New Zealand and Australia to empower businesses and sectors to improve existing products and adopt new approaches to product innovation.

“The partnership is ideal because thinkstep can define the whole life cycle and connect it with Cradle to Cradle® by understanding it as a nutrient. This helps to understand the system in a digital world.” – Braungart

Combining Cradle to Cradle® design principles with quantitative impact assessment using LCA enables businesses to create a positive footprint in this part of the world. This includes focusing on impacts using a systematic methodology, certification of products, tracking of healthy materials and calculating material circularity indicators.

Splendid isolation is our advantage

Prof. Braungart encouraged us to turn our isolation and our size into our advantage. “New Zealand could become a Cradle to Cradle® nation with a net-positive impact instead of a reduced negative footprint.” The pulp, paper and printing industry and the steel sector could be starting points, following in the footsteps of wool.

Michael’s last major presentation in New Zealand was in 2008. He promised it wouldn’t be another ten years before he returns. It might even be as early as 2019 to check if we have started moving on from doing less bad to doing more good.

Leave a comment