“Schools close as tummy bug spreads”

“Animal faeces in water supply”

“Tap water in NZ town causes hundreds to fall ill”

“Poisoning the wells – infected drinking water in Canterbury.”

According to Canterbury District Health Board figures, the region now has the highest rate of campylobacter infections in the world, along with 17,000 notified cases of gastroenteritis a year and up to 34,000 cases of waterborne illness annually.

These are not headlines we should associate with New Zealand’s freshwater.

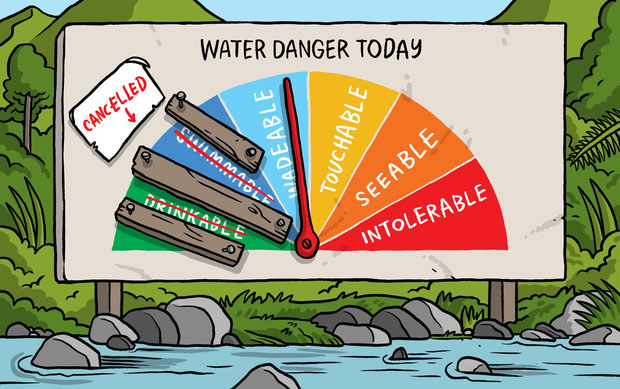

It’s clear that water quality in New Zealand is deteriorating. Increased algal blooms containing toxic levels of bacteria are polluting our waterways and 75% of native freshwater fish species are threatened with extinction.

Environmentalists, farmers, politicians, citizens and professors have joined the debate over the cause of NZ’s water crisis.

Herald columnist Raybon Kan suggests that:

“New Zealand should change its slogan from the quite limiting, auditable ‘New Zealand: 100% Pure,’ to the much catchier ‘New Zealand: Much Cleaner Than Chernobyl.’”

Water contamination in rivers and wetlands is becoming more common. In January, I wrote about metre-deep red algae piled up on Waipu beach. These events are now occurring with increasing regularity.

In fact, studies of New Zealand lakes indicate that 44% are so polluted with nutrients that they are now classed as ‘eutrophic’ (contains excessive phosphates, nitrates and organic nutrients).

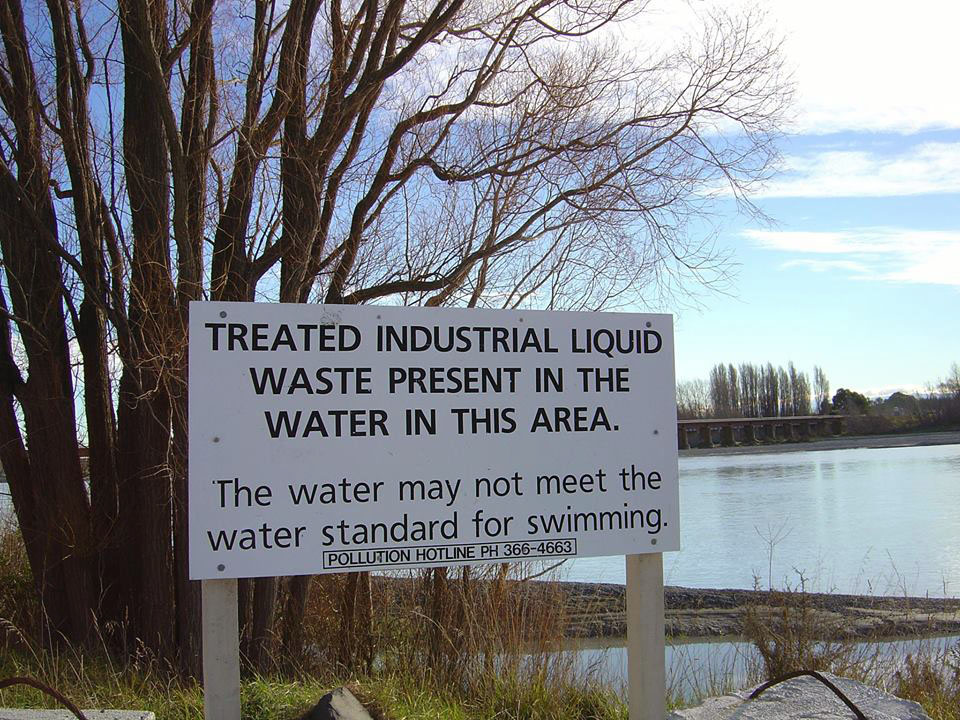

Canterbury’s fresh water has recently been contaminated with E coli bacteria at 70 times the safe limit for human consumption. High levels of E. coli contamination make nearly two thirds of New Zealand’s rivers unsafe to swim in. However, Canterbury’s rate is about a third higher than the national rate.

In addition to the Canterbury crisis, nearly 5,000 residents in Havelock North fell ill from Campylobacter after the local water supply was contaminated – likely from ruminant farm animal feces.

During heavy rain and high flows many rivers contain debris, sediment and pathogen runoff from farms, homes, streets and sewage systems.

Havelock North resident, Rachael Campbell said “It’s a real concern that we can have a massive rain event that triggers this scenario – we are not third world, we should be able to turn on our tap and have fresh drinking water. It’s a huge wake up call to me – we rely on our freshwater supply to be safe and drinkable.”

University of Otago botanist, Professor Sir Alan Mark says the Havelock North water contamination crisis is a ”major wake-up call” about the need for more sustainable agriculture and better protection of drinking water.

Raybon Kan remarks, “It strikes me we’re not quite outraged enough about Havelock North. Are we conflicted, because we also like beef and cheese? What would it take for us to be nationally outraged about toxic tap water? We’d need the All Blacks to play a test in Hawkes Bay, a World Cup final against South Africa, and we’d need the whole team to be poisoned by tap water the night before. Maybe then we’d care. There’d be a manhunt for Suzy the waitress.”

So what’s causing the pollution?

New Zealand’s economy has heavily relied on grazing animals for the past century – threatening the health of our waterways. Our landscape has become highly productive and profitable, but the impact on our water has been significant. In the upper reaches of the Waikato River towards Taupo, the water is pristine. But in the lower Waikato about 97% of sites are unsafe for people to swim because of high fecal loads.”

“If we all own the water, as the Prime Minister says, why has the Government set the bar for water quality in New Zealand so low? Whose interests are they serving? Kiwis want rivers, lakes and harbors they can swim and fish in, and pure, safe drinking water.” – Dame Anne Slamond

Professor of Biological Sciences at Waikato University and Bay of Plenty Regional Council Lakes Chair, David Hamilton, believes that ‘diffuse’ pollution from the intensification of a range of activities including beef, dairy, sheep, and horticulture is a major cause for concern.

“This effect is most acute in the lowland areas of New Zealand where shallow lakes and estuaries are most susceptible to nutrient inputs, and where most of the intensive agriculture is centred.”

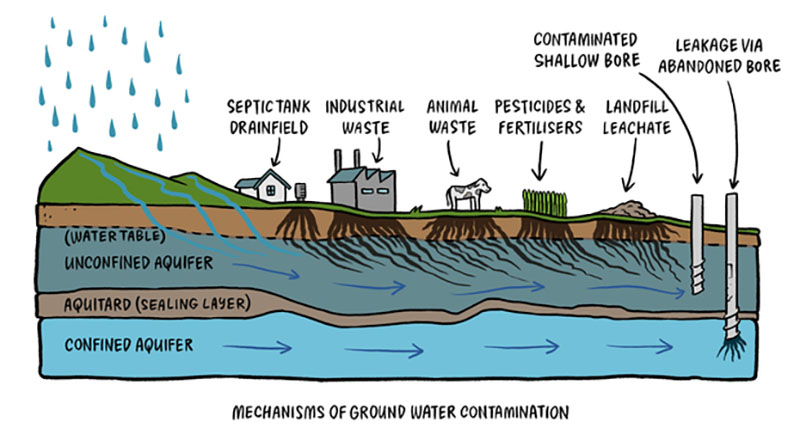

According to Environment Canterbury’s projections, climate change will increase temperatures and decrease rainfall, leading to less replenishment of groundwater and lower river flows. Dry areas such as Hawkes Bay and Canterbury that rely on aquifers for drinking water may see irrigation demand increase amid more water shortages.

As the global supply of water shrinks, it will become more valuable. Over 99.7% of earths water supply can’t be used by humans, and the remaining amount is shrinking due to population growth – with over 70% of earths supply being used for agriculture.

“We don’t want to see world wars fought over water… but we’re already seeing tensions between nations over water supply.” (Lord Michael Hastings, KPMG International’s Global Head of Corporate Citizenship)

All natural water bodies contain bugs (pathogens) that can make us ill if a microbial imbalance occurs. The more bugs, the greater the health risk. “In the case of E. coli, giardia and campylobacter, the increased number of dairy cows means increased loads of microbial contaminants to waterways.” – Professor David Hamilton

A study last year found 50% of New Zealand farms surveyed had calves with cryptosporidium in their faeces, 70% had rotavirus and 4% had salmonella.

One dairy cow excretes the fecal bacteria equivalent of 14 people, which means the national dairy herd produces as much fecal bacteria as 90 million people every day. And most of that isn’t going through a sewage treatment plant. This creates toxic bacterial blooms that are detrimental to human health and biodiversity.

Without proper fencing, dairy cows enter and erode river banks. Effluent, phosphorus run-off from fertilizer, and nitrogen from cow urine leaches through the soil and into the waterways causing algal blooms. “Add to this the silt, sand and topsoil washing off New Zealand’s denuded hillsides and well-trodden pastures and it seems the country’s entire freshwater system is at risk of choking to death.”

Initiatives are progressing. According to the 2015 Fonterra annual report, 98% (24,352 kilometres) of defined waterways on mapped farms are stock-excluded.

Optimal fertiliser management can keep fertiliser out of waterways by individually testing paddocks to find the appropriate amount of fertiliser for healthy soil conditions. Fencing regulations and riparian planting also help keep cows and effluent out of the waterways.

“We have to realise that most riparian planting is cosmetic, but should be encouraged because it stops direct stock trampling of waterways in association with fencing off. But the riparian areas we are prescribing are simply too small to have a major impact on nutrient and microbial contaminant losses from farms. We need to re-engineer the landscape. We need a whole lot more trees and buffer areas. They have largely achieved this in many areas of Europe and have had enormous success in bringing waterways back to good health.” – Professor David Hamilton

NZ has more cars, more waste, more livestock, more fertilizer, and comparatively less forestry than ever before. The 2015 Environment Aotearoa report found that between 1996 and 2014 we lost more than 10,000 hectares of native forest and regenerating forest. That’s 10,000 international rugby fields!

Protecting water quality will mean protecting the native forests in upper catchments that help maintain steady water flows. Ground-based filtering removes damaging micro-organisms, and protects bore water supplies. Trees provide shade and cooler water which encourages native aquatic life. Protecting wetlands increases water quality and mitigates flooding.

© Steve Curtis

So who is responsible for the health of our waterways?

There is debate as to whether the cost for restoration should be directed to the major polluters (intensive farmers) or whether costs should be shared by tax payers.

We all drive consumerism and contribute to the health of our waterways. Professor Jacqueline Rowarth from Waikato University Professor of Agri-business believes “there has been fad pointing of finger” and farming shouldn’t be solely to blame for NZ’s series of water contamination outbreaks.

“New Zealand is a rich country. It is perfectly possible to provide the necessary safeguards and the protections which would have stopped something of the crisis that Hawke’s Bay has been.” – Lord Michael Hastings, KPMG International’s Global Head of Corporate Citizenship.

Andrew Hayes manages Lakeland dairy Farm at Horsham Downs, which is a showcase site for both sustainable management and peat lake restoration. “He has been re-engineering his land, his farming system and at the same time has increased profitability. Essentially he is removing the legacy of his past practices and going beyond that.” – Professor David Hamilton

“If you can find simple technologies that are environmentally friendly but also profitable, then farmers will be more willing to take up those technologies rapidly.” – Environmental Economist, Professor Graeme Doole

Taupo Beef won the 2015 Sustainable Business Network supreme award for its sustainable farming practices and commitment to Lake Taupo’s water quality. More than a fifth of the 146-hectare farm is either set aside for conservation, or is river bank that has been replanted with native flora. Taupo Beef has successfully converted their farming system to protect the waterways and produce high quality beef demanding a premium price. To achieve high water quality standards for our rivers and lakes consumers need to be actively involved in the solution. Taupo Beef has internalized environmental costs into a premium product, portraying the value of creating markets to reward improvement instead of pollution.

“The reality is that without the pressure of super-production, dairy farmers will take the ethical path they want to, as stewards of our land, our taonga.”- Former local politician and farmer, Tim Gilbertson

Experts suggest that kiwis can do a better job at finding out about the origin and impact of their meat and dairy. Even more importantly New Zealand needs to diversify the economy away from beef and dairy production.

“We need to translate local concerns about degradation into a national scale strategy that makes sense.

The Crown is allocating $7 million per year to “clean up” the Waikato River. At the same time through Land Corp, it has been supporting the removal of pine plantations and conversion of that land to dairy farms in the upper Waikato River catchment. Another example: despite the fact that we have less than 10% of our pre-European wetlands still remaining, there is an annual net loss of wetlands in New Zealand. Something is wrong here.

If Europe can implement green policies, put a whole lot more trees on the landscape and reap the rewards of good environmental legislation (the EU Water Framework Directive), then surely New Zealand can?” – Professor David Hamilton

We must take responsibility for the health of our waterways by planting native trees, canvasing local government, supporting sustainable farming, and educating family and friends about critical water issues. Clean and green used to refer to our once pristine environment, but now gives reference to the newly printed bank notes exchanged for the white gold.

Leave a comment