Do you have the feeling that COP21 is profoundly important, but you’re not entirely sure what’s at stake?

No worries! I’ve been following the lead-up to COP21 throughout the year—from Our Common Future Under Climate Change, the major science conference in Paris prior to COP21, to the Australia-New Zealand Climate Change and Business Conference in Auckland.

Here’s ten things to keep an eye on over the course of negotiations, the latter having special relevance to New Zealand…

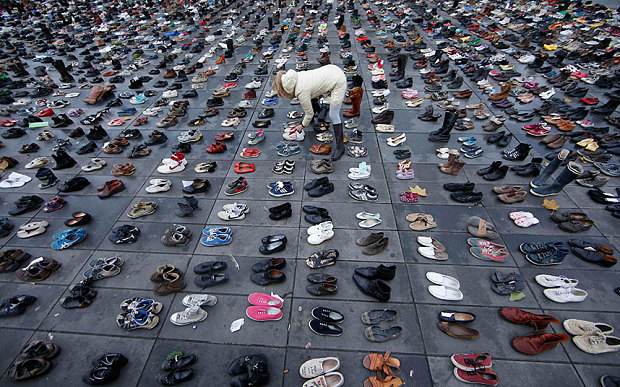

The authorities in Paris have banned any protest marches due to security concerns following the terrorist attacks, so campaigners have left their shoes out instead Photo: REUTERS/Eric Gaillard

1: Will we get a collective long-term goal?

This is what most people expect from COP21. To be sure, a global cap on emissions would be a clear-cut political triumph, especially for negotiators still feeling burned by the deadlock at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009.

The last draft text for the Paris agreement (released October 23rd) gives some ballpark figures. Article 2 proposes holding the global average temperature below 2°C or below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. In Article 3, there are options for a 40–70% or a 70–95% emissions reduction below 2010 levels by 2050. There are also options for net zero emissions by 2050, or 2100, or sometime in the period 2060–2080.

Negotiators will haggle over some combination of these. Or they might abandon the collective long-term goal entirely. This is still a distinct possibility, given that a second version of Article 2 discusses national targets only, with no mention of global targets.

To many folks, this would seem like a major cop-out. Certainly, at the climate/business conference in Auckland, the prevailing expectation was a global emissions target.

In Paris, however, views were more mixed. Many scientists were reluctant to raise expectations, keen to avoid recreating the hype and overconfidence that preceded Copenhagen. But there’s another school of thought which contends that a collective long-term goal isn’t the only important outcome, and perhaps not the most important outcome at all. Which leads me to the next point…

2: Will national targets establish themselves as the new lever for international action?

This year’s Conference of Parties (COP) is unique. Most nations are arriving at COP21 with a declaration of post-2020 emissions targets. These declarations are known as “intended nationally determined contributions”, or INDCs for short.

Each INDC was supposed to reflect each nation’s highest possible ambition in light of its national circumstances. When taken together, however, it’s been estimated that current pledges would only steer the world to 2.7°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century. That overshoots the consensus view: that warming should be limited to 2°C.

Fortunately, INDCs aren’t set in stone. Think of INDCs—and other pledges—as the scruff of government’s neck. By exposing them, governments become more vulnerable to being dragged into action—by other governments, by global civil society, or by their own citizens.

New Zealand has already come under some criticism for its 2030 target: a 30% reduction from 2005 levels, equivalent to 11% below 1990 levels. Public submissions expressed widespread discontent with government strategy—which will exert growing pressure on parliamentarians. More to the point, law student Sarah Thompson filed papers this month in the High Court in Wellington to challenge the legality and reasonableness of the government’s pledges. How this plays out will take us well beyond the window for COP21—but it’s a reminder that the struggle against global warming won’t stop in Paris.

There’s also a chance that levers will be built into the Paris agreement through a so-called “ratchet” mechanism. In September the US and China signaled that a successful agreement would be one that “ramps-up ambition over time.” That means a running target for any country that’s taken the slow-starting strategy of “fast follower” on climate change.

3: What will the process of review be for INDCs?

If you’re a pessimist about global agreements, but an optimist about political accountability, then what should interest you most is the review procedures for INDCs.

At this stage, the review mechanism is thoroughly unresolved. It exists in draft texts as a smorgasbord of options that could be piled together in various ways. The issues that might crystallise include:

- How often will reviews take place? There is momentum toward a five-year review cycle, but draft texts have floated other options, including a ten-year cycle.

- Who will conduct the review? Will it be countries themselves, the UNFCCC, or an ad hoc entity?

- Will the reviews focus only on the transparency of INDCS, on whether or not countries truly meet their targets? Or will it be a comprehensive review that includes issues of adequacy and fairness, like a more formal version of Climate Action Tracker?

- Will the INDCs and reviews focus only on emissions reductions, or will they be expanded to include adaptation, finance and technology?

If this review process is given some teeth, then even without a collective long-term goal, a pledge-and-review regime could carry on. Arguably, this bottom-up piecemeal approach has already delivered a modest victory, by securing individual declarations that collectively steer us away from our current trajectory of 4.1–4.8°C above pre-industrial levels.

4: How binding will the agreement be?

Another common expectation is that the agreement be binding. But that doesn’t say enough.

International agreements are extraordinarily complex. At COP21, there are all sorts of demands and proposals on the table, including global targets, national targets (INDCs), adaptation measures, financing arrangements, technology transfer, capacity building, climate justice, and more. It’s also a diplomatic strategy to offer to loosen the “bindingness” of one issue (say, adaptation) in order to tighten another (say, global targets).

The real issue, then, is which elements are binding, and how demanding those binds are. If an international agreement is a rope to tie the hands of decision makers, then it’s a rope made of multiple strands, some less rigid, less demanding, than others.

Certain words signal the level of commitment. A lot hangs on the distinction of “should” and “shall”. If a clause specifies what signatories should do, then the obligation is loose, more like a guideline. But if it starts talking about what countries shall do, then we’re talking about mandatory requirements. These become weightier if they’re time-bound, and weightier still if the word “implement” pops up.

5: What are we going to call this thing?

A treaty? A protocol? An accord? This might seem a trivial issue but, in international diplomacy, words carry a lot of weight.

COP15 at Copenhagen in 2009 resulted in the Copenhagen Accord, which wasn’t legally enforceable. Given the sense of failure, there’s an understandable desire for something more grand, more muscular, than an “accord”.

At the 2011 Durban Platform, negotiators agreed to agree to “a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force”. The EU has already used the Paris Protocol for its formal communications, which partly reflects the EU’s ambition for a legal form with bite.

But John Kerry recently ruled out one form in a Financial Times interview when he declared that the COP21 agreement was “definitively not going to be a treaty”. This sparked a minor kerfuffle among his European counterparts, but there was a crucial issue at stake.

Under international law, not much hangs on the term “treaty”. But under US constitutional law, a treaty has a specific legal status which means it must pass through the Senate for approval. Given that the Senate is currently controlled by the Republican Party, that’s a sojourn that no climate-conscious politician would wish for.

6: How much integrity do targets have?

As the saying goes, a goal is not a strategy. Global targets and INDCs are hollow if there’s no credible plan for fulfilling them. Some options within the draft text could tighten the screws, especially the draft version of Article 11 which has options for an International Tribunal of Climate Justice or compliance action plans.

These could exert pressure on New Zealand’s current approach. Our Emissions Trading Scheme is trumpeted as a substantive policy response to climate change. But it isn’t a response: it’s an instrument, and an instrument that’s been poorly utilised throughout its lifespan.

At the climate/business conference in Auckland, I saw the growing momentum for a Climate Forum, an idea being spearheaded by the Environmental Defence Society. This would involve a platform where government, business, and environmental interests worked cooperatively to develop a credible low carbon pathway, similar to the Land and Water Forum. Although, given the latter’s troubles of late, there is cause for caution alongside opportunity.

7: Will the Green Climate Fund be made more binding?

There is a long-standing ambition to create a US$100 billion by 2020 for so-called “developing countries”, to be administered through the Green Climate Fund. This option is included in the draft text. It is potentially a major bargaining chip, because some developing countries are reluctant to agree to global targets if it’s seen to hinder their path to development (or, more precisely, their industrialisation). The offer of aid could reset that balance.

These tensions are, perhaps, the greatest hurdle to a global agreement. Negotiators represent the interests of countries with different economic situations, different aspirations, and different historical responsibilities for emissions. That complexity is recognised through the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility”, a mainstay of climate diplomacy, yet which seems a difficult principle to put into practice. When cost is involved, it’s all too tempting for some politicians to avoid responsibility.

New Zealand’s pledge for the Green Climate Fund is US$2.56 million (NZ$3 million). That amounts to US$0.56 for every New Zealander. This is well below the per capita contribution of other nations like the UK (US$18.77 per capita) and USA (US$9.41 per capita). Sweden, naturally, romps in ahead by contributing almost US$60 per Swede.

8: Will land use, land use change, and forestry get a mention?

Land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) refers to the carbon released and sequestered through deforestation, afforestation, and other land use changes. These issues are likely off the agenda in Paris, given that the EU deferred the issue until 2016 (LULUCF was included in an earlier version of its INDC). Other major players like the USA and Brazil already include LULUCF in their INDCs.

New Zealand excluded LULUCF from its INDC. If it stays off the agenda in Paris, that’s a major reprieve, given that New Zealand is presently in a state of net deforestation—with many more forest owners signaling their intention to switch to dairy in future. Given that the EU will revisit the issue of LULUCF soon, this is another situation where New Zealand’s laggardness creates major risks for future generations.

9: Will the Paris text incorporate distinctions among greenhouse gases?

This is an issue that Tim Groser, New Zealand’s Minister for Climate Change Issues, explicitly wants movement on. He’s argued that, in a world of growing population and rising food scarcity, greenhouse gases emitted through food production—in particular, methane—should not be held to the same account as carbon dioxide.

Will we see change? Certainly, there are problems with Groser’s argument, not least the fact that methane is a problem for intensive dairy farming especially, not food production generally. His talk of “a binary choice between climate change and food security” is a false dichotomy. Nevertheless, by distinguishing amongst greenhouse gases, there is scope for more sophisticated mitigation strategies which take account of gases varying lifespans and heat-trapping properties.

10: Will there be substantial efforts to prepare for climate-change induced migration?

Another issue of particular interest to New Zealand is the so-called “climate change displacement coordination facility”. The case of Ioane Teitiota, New Zealand’s first would-be climate refugee, exposed the legal vacuum for people displaced by rising sea levels. Given New Zealand’s proximity to many low-lying small island states, this issue won’t going away.

The proposed coordination facility could involve funding, technical assistance, legal guidelines, and support for displaced peoples. But the plan clearly has its detractors. It was removed from the penultimate draft text, reportedly due to Australian lobbying. It has since reappeared in the final draft.

(The author’s presence at the Our Common Future Under Climate Change conference in Paris and the Australia-New Zealand Climate Change and Business Conference in Auckland was made possible, respectively, by the European Union’s Delegation to New Zealand and the Environmental Defence Society. The views given above are the author’s own.)

Leave a comment