The Paris Agreement (PA) has been labelled as the most successful, broad and flexible of environmental agreements, where each country sets their own Intended Nationally Determined Contributions and elaborates on the policy actions necessary to comply with targets.

For New Zealand, policy actions may involve the expansion of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), regulations on manufacture and production systems, limits on GHG-intensive inputs, or incentives to develop clean technologies. In any case, policies generate costs and responses from the economic sectors affected (Fernandez and Daigneault 2016a). Those responses will depend on the burden that emitters will have to carry in order to comply with environmental mandates. Consequently, to test whether the Net-Zero target is economically feasible, the key issue is to ascertain how those costs shape the capabilities of the country to meet it.

There is a range of economic issues to consider.

The Vivid Economics Report acknowledges that half of domestic GHG emissions come from agriculture where technological options to mitigate methane and nitrous oxide are still in development stages. In addition, since most of New Zealand’s energy comes from renewables, further requirements for reductions do not leave much room to decarbonise emissions without emitters having to incur losses. Thus, the purpose of the ETS was to introduce flexibility on environmental policy so that emitters may find the lowest cost or the most efficient alternatives to comply with reduction targets. Contrary to command-and-control mandates, the ETS allows emitters to freely accommodate environmental efforts in their production or manufacture systems. Currently, the ETS prices GHG emissions from non-agricultural sources only and is one of the country’s main policy responses to climate change. However, it is not clear yet what the role of other policy alternatives, such as forest carbon sequestration (FCS), will be. That is, whether FCS will make a difference on meeting the Net-Zero target if accounted to calculate NZ’s net GHG emissions.

Pricing agriculture has become a sensitive political issue where every comment is scrutinised and questions arise about how to incorporate agriculture in the ETS. Plus, the ETS is mainly a domestic scheme as it is not linked to any other foreign ETS, that is, NZ emitters cannot buy emission permits on any other country and surrender them in NZ to comply with GHG limits. At least, in theory, linking would open the doors to a wider and more affordable pool of emission permits (Anger et. al. 2009). However, if this linking policy is contemplated, the first (big) hurdle to overcome would be to find another suitable ETS to link with. Years ago Australia dismantled its carbon market, the USA has just pulled out of the PA, and only the EU remains as a large (and mature) enough market where linking could be explored.

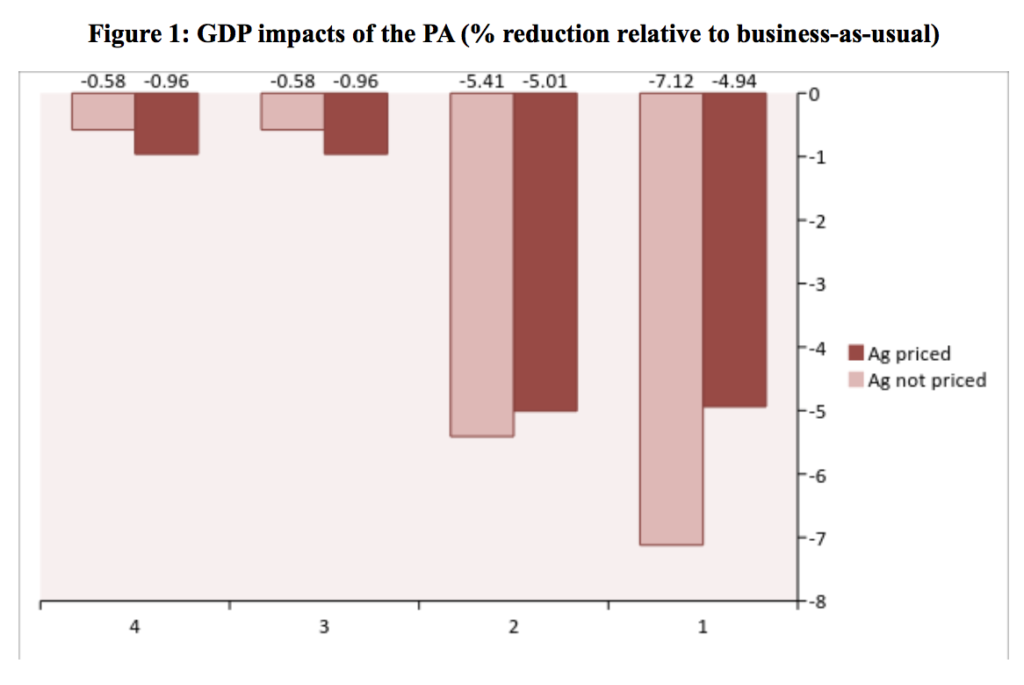

Complexities aside, the environmental success of NZ needs to be coupled with the economic costs of following any road consistent with the Net-Zero target. Fernandez and Daigneault (2016b) explore the responses of the economy to constraints imposed by the PA, as well as the role of agriculture being part of the ETS, the contribution of FCS and the potential effects of linking the NZ ETS with the EU. The economic cost is measured as the loss of GDP relative to a business-as-usual (baseline) scenario where the PA commitments are not binding.

Figure 1 shows some interesting insights.

Adapted from Fernandez and Daigneault (2016b)

Under the current conditions where agriculture is not priced, FCS is not accounted and ETS remains as a domestic scheme, the PA commitments are met but NZ GDP would be about 7% lower compared to the baseline scenario. This GDP loss may be moderated to 5% if agricultural emissions were priced. This moderation occurs because the burden of the mitigation effort would be spread on a larger number of economic sectors. Moreover, if the ETS links with the EU, GDP losses are relatively lower but still remain significant. That is, contrary to research results in other OECD countries (Lanzi et al. 2013), linking does not necessarily imply gains for NZ emitters because of higher permit prices and potential losses of competitiveness (Anger 2008). Hence, in addition to negotiation and coordination costs between EU and NZ, linking does not add value to NZ and may not be a desirable policy goal (Fernandez and Daigneault 2016a).

More importantly for the purposes of compliance costs, accounting for FCS can make a huge difference. Regardless whether agriculture participates in the ETS, and whether the ETS is linked or not, GDP losses are less than 1% relative to the baseline scenario. That is, ETS expansion and linking become redundant, in terms of environmental effectiveness, when compared to FCS.

The bottom line of this discussion is the significant role of forestry and the complementarities with other policy alternatives. The ETS per se may not be that effective (relative to other alternatives) on achieving environmental targets but may serve as a mechanism to stimulate positive responses from foresters, e.g., by motivating large restoration projects involving tree-planting where co-benefits such as erosion and sedimentation control may occur. Therefore, a policy mix that includes and maximises forestry carbon sequestration would make the Net-Zero target more affordable.

Leave a comment