The critical responses to the release of the NetZero report were predictable. Land use changes, a central pillar upon which the four scenarios were built, and the requirements for a significant reduction in the country’s dairy herd, raised some eyebrows, and were deemed to be unrealistic, as they would have “major implications for the economy“. Specifically, the impact on economic growth would be too great. But what is so important about economic growth?

Economic growth is, so we are told, how we maintain our standard of living, the way we create a better society for all. It is the focus of our Government’s policy who promise to, “drive economic growth for the benefit of all New Zealanders”. Growth, as measured by GDP, is the single measure that most governments, including ours, use to determine success. And it is true, economic growth has brought with it significant benefits. The problem is that it has also come at a cost, resulting in, for example, rising inequalities and the degradation of our rivers. Furthermore, it is not something that can go on forever.

In my previous piece, I asked ‘What’s Next?’. Arguing that our current economic model was inconsistent with a sustainable future, I made a call for business leaders to seriously think about what the next model could be, a model based on science, not ideology. A model that did not try to hide away from the reality of living in a finite world, that did not accept that economic success had to be at the expense of social equity or at the cost of environmental degradation.

Well, it appears that model does now exist. Despite the playful title, ‘Doughnut Economics Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Cornerstone’, written by Kate Raworth of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute is an insightful, well-researched book that provides us with a compelling alternative to the growth obsession.

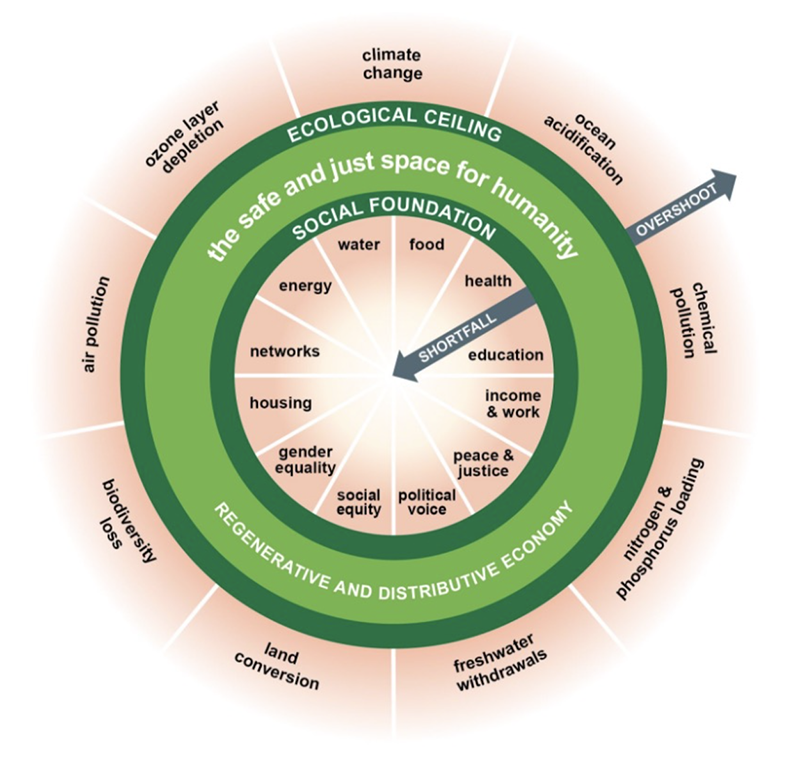

Credit: Kate Raworth

The Doughnut: a twenty-first century compass

The essential argument put forward by Kate is that the economic ‘sweet spot’, she is talking about doughnuts after all, lies in that space in which we are not exceeding the planetary limits, while, at the same time ensuring that we provide for the social wellbeing of our citizens. Those living at the centre of the doughnut are deprived, not receiving what we know are the necessities for a healthy life. Outside the doughnut, we are pushing beyond the limits of our planet to cope. The model offers us a framework to talk about economic success, that takes us beyond the narrow confines of the growth mantra.

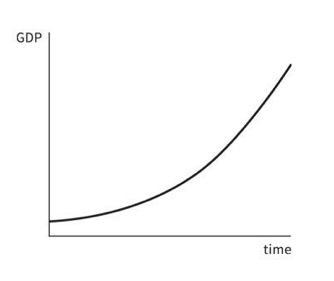

To highlight the totally idiotic and illogical nature of that central pillar of our current economic model, Kate Raworth asks us to undertake a simple exercise. Get a piece of paper and draw the long-term curve for economic growth. It will be an exponential curve, that gets steeper and steeper and, if you go on long enough will be going straight up. No wonder economic texts never draw such a curve, even though it is the logical trajectory of the key economic indicator of success, GDP growth per year.

In NZ, GDP growth is currently around 3% per year, which means our economy will double in 23 years (2040), and double again by 2063. By the end of this century, within the lifetime of those being born now, the economy will be over 10 times bigger – not because of inflation, but by the logic of compound growth. Given the problems we are currently confronting, it is hard to envisage what NZ would be like with an economy 10 times larger than it is now. Our current concerns about crowds of tourists on our Great Walks, the state of our rivers, or the traffic chaos in Auckland will pale into insignificance. Some may argue, however, that growth of that scale is possible for NZ, given our landmass and small population. But, this same logic applies to the world, where GDP is also growing at around 3% a year. Can you really imagine a world economy 10 times larger than it is today, given the stresses we are already grappling with? The fact is that exponential growth cannot go on forever, the curve can’t simply keep going up, it is physically impossible. A more realistic future growth picture is the S curve:

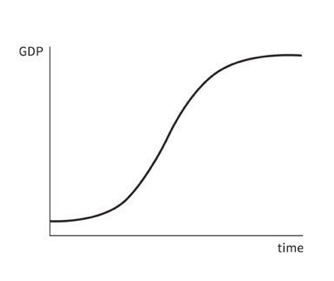

Known as logistic growth, the ’S curve’ has been shown to fit very well with growth patterns we see in the natural world and highlights that growth will always, at some stage, plateau. So, the important question is not what impact NetZero by 2050 will have on our GDP growth, but how achieving NetZero will impact our ability to thrive and prosper regardless of the level of GDP growth. The reality is that growth will not, cannot, go on forever, so debating whether achieving NetZero, over the next 35 years, is going to affect economic growth is the wrong debate to be having. We need to stop equating economic growth with wellbeing.

As Kate Rowarth points out, “The twentieth century bequeathed us economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive…. Twenty-first-century economists, now face a challenge…to create economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow”.

So, if GDP is to be taken off its pedestal, and become one of many important measures, what will the Doughnut replace it with? As the model shows, the economic goal is to ensure that the social foundation is laid so that no-one falls into the centre of the doughnut which however it is created, is a condition of deprivation. Furthermore, the model also shows that we cannot grow to the extent that we push against, or break through, our ecological ceiling. And, to the model’s credit these boundaries are explicitly stated, and able to be measured.

The foundation for human wellbeing has been well described by the social priorities within the UN Sustainable Development Goals and agreed to in 2015, by 193 member countries, including NZ. The ceiling, created by our planetary limits has been well researched and in a number of areas, we are already beyond what is safe, in others at risk of overshoot while others still need more research to understand the position clearly. Using this model as our framework it is clear that NZ has several areas that are of concern; water, housing, social equity, and gender equality being four areas that are regularly in the headlines. If we used the ‘doughnut’ as our indicator of economic wellbeing, and our ability to live within our planetary limits, we certainly have areas to work on. Inside the doughnut are the more than 300,000 children living in poverty, children who don’t have enough to eat and whose families cannot afford them a decent school lunch. Outside of the doughnut we are pushing our planetary limits. Our CO2 emissions per capita are still growing while other countries are heading downwards. The nitrogen and phosphorus load on our land is now a regular issue debated in the media, especially in regard to its impact on water. Our freshwater withdrawals are of major concern and in terms of biodiversity, we have a very unenviable track record. We are reaching, and sometimes exceeding our planetary limits, potentially destroying the nine critical processes that have, since the dawn of mankind, created the conditions for us to flourish. Push beyond these limits and the stability of our home is jeopardised. This is not opinion, but hard science, the kind of science that Sir Peter Gluckman, our Chief Scientist, says is needed to inform our policies. By the metrics of the doughnut, New Zealand has a lot to do.

NZ is not operating within the ‘sweet spot’. Too many New Zealanders are ‘inside the doughnut’, not able to access those necessities that are the right of every human being and, despite our small population we are also pushing the planet beyond its limits.

As we are increasingly forced to confront the realities of the 21st Century, in which we must confront the idiocy of our addiction to continuous economic growth, Kate Raworth has provided us with an alternative organising framework. It is a framework that enables us to have challenging conversations about the future we want for New Zealand and how a NetZero future can contribute to that future. It is a framework that enables us to move beyond the simplistic notion of an ever-growing economy and the assumption that it will deliver prosperity to us all, to discussions about how we design an economy that brings us into the sweet spot, that provides prosperity for New Zealander’s within the limits of our planet.

So, debating our pathway to a net zero future should not just be a debate about greenhouse gases, but a debate about the sort of country we, our children and grandchildren want to live in.

Leave a comment