The term ‘permaculture’ was first coined in 1978 by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren and is a contraction of ‘permanent culture’. The basic qualification is the Permculture Design Certificate. Some of the practises and ideas that were once radical or groundbreaking have become widespread, both in food production (e.g. mulching gardens for soil conditioning and water retention) and increasingly in the sustainable business literature (many of the principles in The Blue Economy and in Natural Capitalism reflect permaculture thinking). Even so, permaculture as a whole-systems design approach still has much to offer to a world in transition.

It is increasingly obvious that humans are at a crisis point. We have created a civilisation that is in fundamental conflict with the natural world. Our great environmental challenges, including climate change, water degradation, soil loss and mass extinction of species are all symptoms of this. The global economy, with its imperative for endless cumulative growth, is reaching the ecological boundaries of our planet. If we want to have a future where humans can thrive, we need to transform. We need to redesign our way of life to become deeply sustainable, creatively resilient and intrinsically regenerative.

Sustainability, Resilience and Regeneration

Being sustainable simply means being able to keep going indefinitely. Sustainability practises often focus on resource efficiency and the substitution of harmful materials, however the Jevons Paradox shows that highly efficient use of resources per unit can lead to increased net resource use. We must consciously address overall levels of consumption.

We need to also focus on resilience – the ability to recover from disruption and to bounce back – given an increasingly uncertain world. Resilience often comes from strategic redundancy, or having ‘fat’ in the system and is often in tension with strategies to make things stronger and more robust.

Regeneration recognises that sustainably managing a degraded environment is not enough. We have slashed so many strands of the web of life that we need to actively stitch it back together by enhancing ecological integrity wherever we can.

The basic premise of permaculture is that systems already exist which are sustainable, resilient and regenerative. These are natural systems. The more we can understand the processes by which natural systems unfold and develop and the more we can grasp the principles and characteristics of ecology, the more harmonious and life-sustaining our own systems can become.

Ethical principles

Permaculture begins with three ethical underpinnings: Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share. Earth Care recognises that we are part of the natural world and that in the most literal way our lives and our well-being derive from it. All of our systems must make provision for life systems to continue and multiply at all levels.

People Care is about creating systems that enhance our humanity. People are complex multi dimensional beings with an innate drive to create, to explore and to express ourselves. We are also social beings so healthy relationships with each other, with our kin, our community, our culture are all vital to our well-being.

Fair share, sometimes expressed as ‘share the surplus’ is an ethic of generosity. This is in contrast to the ethic of selfishness and accumulation which is at the heart of neoliberalism. Excessive accumulation and personal consumption leads to insecurity and instability and only by sharing resources more justly can we become genuinely sustainable. By being modest with our own consumption we can set resources aside to support the broader transformation needed.

Design principles

Out of the permaculture ethics comes a series of design principles. They arise from the contemplation of nature, observation of indigenous and traditional practises and from science – in particular the sciences of ecology and of physics. There is no single definitive list of them, but David Holmgren’s 12 Design Principles are perhaps the best known and most cohesive articulation.

However, permaculture is not just about memorising a formula. It is more about understanding the underlying patterns that exist in nature and applying them to the specific circumstances. When we say design by nature, it is not a metaphor, but an acknowledgement that in any situation a set of self-organising forces already exist that we need to recognise and integrate with our own intent.

Permaculture, then, begins with thoughtful observation and interaction. When developing a property, permaculturists are encouraged to spend a year on their land before doing anything major. This allows time to observe the seasonal changes and to see the pre-existing patterns in the ecosystem. Within a tighter time-frame, careful observation can still indicate where the energy and resource stocks and flows are, the water, sun, wind, nutrients, wildlife and people. We can observe the niches and microclimates, the natural pathways of people and animals and where the biggest opportunities are.

Essentially the same process takes place when applying permaculture design to a social or economic project. We attempt to draw out the latent potential of a ‘site’ rather than impose an artificial concept developed in isolation from the real situation.

Food Forests – an illustration

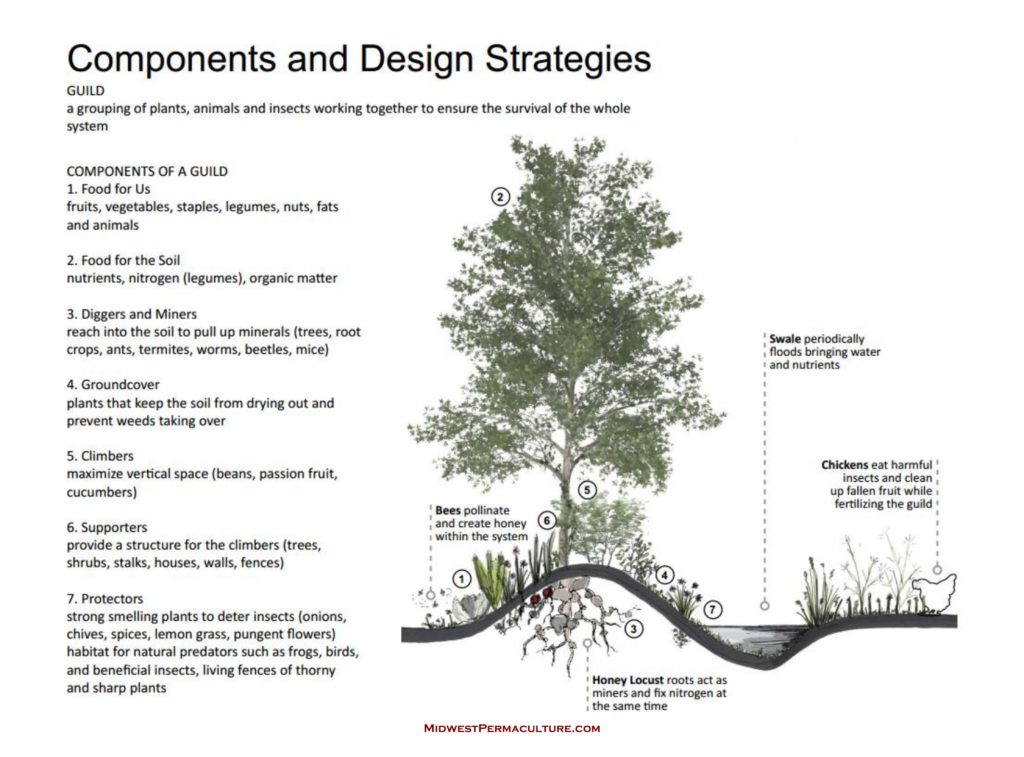

Food forests are not a universal solution, but they do offer a good illustration of how permaculture design principles can come together. Rather than a monoculture orchard with rows and rows of a single variety of a single species with bare poisoned earth between them, a food forest is a polyculture that attempts to mimic a natural forest, but one that is based around human need.

A food forest will be diverse in species, which builds resilience to disease and provides a wider range of yields. It will include some leguminous trees, perhaps grouped with different species of fruit trees, to fix nitrogen and act as an insect break. A forest is layered horizontally and temporally so it might have: canopy trees for fruits, nuts and timber; low trees for fruit and coppicing; shrubs for berries and weaving materials; herbaceous bushes for teas, dyes, medicines, mulching; rooting plants for food and to cultivate the soil; soil covers such as fungi, strawberries, culinary herbs; and climbers that penetrate all the layers. Plants will fruit at different times to assure a year-round supply of food and animals may be part of the system, to control insects and plants, and to manure the ground. The ground itself may be ploughed or contoured into swales to trap water and nutrients using a keyline approach.

Perhaps more than anything, permaculture is about increasing the beneficial relationships between things. A permaculture maxim is that every element should fulfil multiple functions, and every function should be supported by multiple elements. In a food forest, for example, a herbaceous plant might be used as a tea or aromatic, to attract beneficial (predatory) insects, to attract pollinators, to mine minerals from sub-soils, and/or to release gases to help ripening.

The self-sustaining ecosystem can be a metaphor for a horticultural food production system, grasslands agriculture, a whole economy, a series of industrial processes, a community organisation or a single business . All of the many characteristics of a healthy ecosystem: diversity, complex associations, layering, making use of locally available and abundant resources, developing feedback loops, building energy stores, can be usefully applied to foster sustainability, resilience and regenerativity in a range of settings. Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the oldest national permaculture organisations in the world and therefore many experienced practitioners who can advance the discussion and highlight the many opportunities.

Leave a comment