Tomorrow’s business managers need an education that looks radically different from my own – and probably from yours too. We need to prepare graduates for a business environment that is not here yet. We need business managers able to respond to megatrends.

A megatrend is not an event, but a long-lasting, disruptive shift. Like a tsunami, it might start small but it quickly becomes irresistible. Organisations that are not able to adapt to megatrends fail; usually quite dramatically. U.S.-based Blockbuster went bankrupt in 2010 and Netflix is now a $28 billion dollar company, about ten times what Blockbuster was worth.

The megatrend challenges that business managers in New Zealand face include: understanding the materiality of climate change for their business; how to include resource scarcity in strategic decision making; recognising the impact of radical transparency on the boundaries of company responsibility and; working with a diverse workforce in terms of age, ethnicity and gender. Any one of those is powerful enough to require dramatic changes in the way a company does business.

Teaching our students about megatrends is not about teaching subject content. Today that sort of information is an electronic click or swipe away. Delivering content, the traditional focus of education, is less and less the focus of tertiary education. Instead, we focus on the capabilities and skills business managers will need to find innovative solutions to the wicked problems facing their industries.

A wicked problem is difficult to solve because of requirements that can be incomplete, contradictory and changing. Often the requirements also are difficult to recognise, or not obvious. Another hallmark of a wicked problem is its connections with issues that may seem unrelated at first glance. Logically, if the problem is interconnected, then the solutions – plural, because there is unlikely to be a single solution — must be as well.

At the same time graduates increasingly want careers where they will make an impact, do something for society and the environment, and/or promote corporate responsibility. In response to these changing realities, Waikato Management School (WMS) at the University of Waikato put sustainability at the core of our purpose in 2004 – before it was trendy!

As signatories of the United Nations’ Principles of Responsible Management Education, we publicly report on the progress toward our sustainability goals and benchmark ourselves against global leaders.

At WMS, our rallying cry is, “sustainability is at the heart of good business”. Sustainability includes the social, cultural, environmental and economic aspects of business. We recognise that long-term business success depends not just on profit, but on responsiveness to social and environmental issues. Few business schools have fully integrated sustainability, but it is baked into our DNA with integration into the curriculum in over 80 courses, in all disciplines as well as specially focussed courses. Sustainability is not tacked on as an elective.

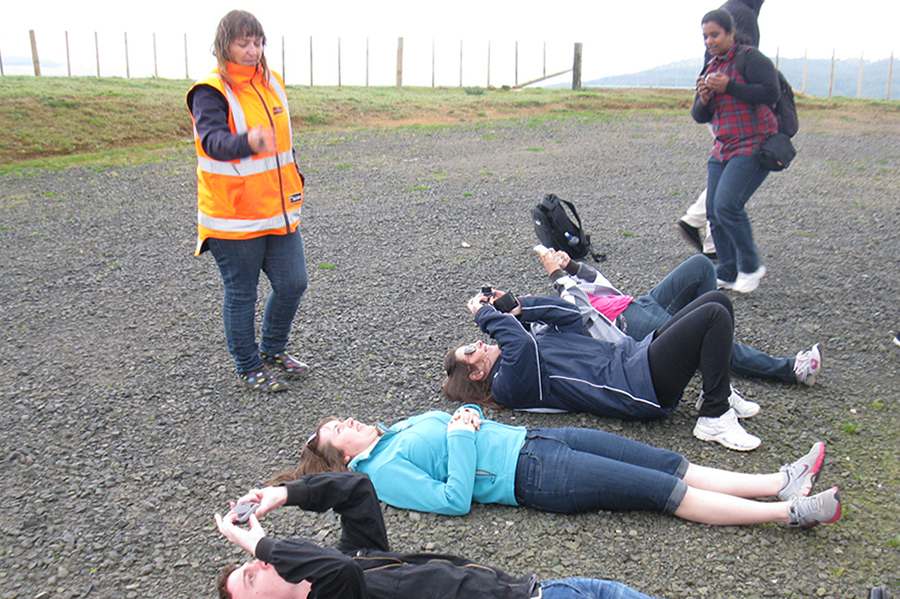

What does this mean for business school education in practical terms? There are three key areas. First, action-based learning has become an important tool for helping students ‘operationalise’ sustainability. For example, internships with corporations and not-for-profits connect students with what is happening in organisations in real time. Another example is in-class simulations on stakeholder negotiations around global issues such as climate change or national issues, such as the Christchurch rebuild.

An action-learning activity I do with my students is ‘Fishbanks’ from MIT. Students engage in class, online, simultaneously working in teams. They build boats, fish, sell their fish and build more boats. The ‘winner’ is the team that has the most net profit at the end of the exercise. The activity is a simplified version of a business based on and dependent on a natural resource. It is in round four or five that I hear the audible gasp in the room when fish numbers that had steadily increased start to drop for the first time.

I have run the exercise with multiple classes and the result has always been the same. Teams keep fishing until the fish stocks are depleted and the boats are worth nothing. Students are always shocked by this outcome. The debrief includes a discussion of finite vs. infinite resources and assumptions about what constitutes ‘winning’ that need to be challenged if we want to engage in sustainable activities.

A second key area of teaching business and sustainability is a systems approach, which means being able to work across disciplines to create meaningful partnerships and opportunities along the entire value chain. Cross-sectoral partnerships – meaning business working with government and/or not-for-profits – can be an opportunity to achieve outcomes that cannot be achieved individually.

Finally, although business models are changing and hybrid models do exist, such as ‘B Corporations’ that enable profit with a purpose, we still teach that business strategies must ultimately yield profits. A business must sustain itself before it can sustain anything else.

However, we want our students to recognise that sustainability itself is a megatrend and so represents a great opportunity for businesses. To benefit from that opportunity, companies will need to make strategic decisions that allow them to take advantage of things like alternative energy technologies, Big Data, creative information management, materials design, and new transportation fuels.

We teach students how to think critically about future challenges facing their world. Our objective is not to produce sustainability professionals, but professionals capable of making sustainable decisions that stand the test of time.

Leave a comment