As the national election comes into view, we find ourselves once again in a 2 meter economy, and continue to rip through billions of dollars in public stimulus, depleting government coffers for the foreseeable time to come. It seems reasonable to assume that social distancing is likely here to stay. As it happens, we also happen to be putting in place the foundational building blocks of a comprehensive climate change policy. Before we move forward and inevitably decide on how we will tie this all together, it is worth taking stock of who we are and where we have gone wrong in the past.

New Zealand has a chequered history in climate change governance, involving many ups and downs, visions dashed or diluted, policies erected but either short-lived or hamstrung by political compromise. Everywhere you look are skeletons; a fuel levy and vehicle purchase feebate scheme, a twice decapitated Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), a short-lived contestable fund for independent power generation, two attempts at integrating agriculture into the ETS, the Fair Go for Solar Bill, and a long history of public multimodal transportation kerfuffle – the list goes on.

Many of these policies were meticulously evaluated, compared and consulted on, but never saw the light of day, others were dismantled once a new government came into office. One effect of this of course, is that we have failed to reduce domestic emissions. I would argue this has also had a second more insidious, deeply cultural, effect – the kind of policy instability that is soul destroying. It destroys investors, industry and the general public’s confidence in the government’s capacity to put in place an effective climate change programme, and permanently puts government and industry leaders off from pursuing their visions and projects for a low carbon economy. The underlying message of National’s long standing Fast Follower rhetoric could be read; we can’t do it, we’re not good enough (we’re too small, we’re too insignificant etc.). This has also encouraged skilled people who want to be part of positive change to leave New Zealand in a search of greener pastures – it will be interesting to see what our returning diaspora brings to the table.

The policy strategies that have stood the test of time are a low level of ambition – they are watered down to appeal across the political spectrum. Energy efficiency, forest sinks and international carbon offsets are the three core areas that NZ has relied on to meet our climate targets under the UNFCCC. These policies are low hanging fruit and have enjoyed bipartisan support because they scored high on short-term cost-efficiency, and they don’t require us to bank on overly complicated or ‘fuzzy’ social, environmental or economic benefits that are difficult to quantify and may or may not materialise over the ensuing decades. The various government agencies that implement these policies are accustomed to this, having learned the hard way that conservative programmes can give you the biggest bang for your buck and are likely to stick no matter what party your Minister is from, whereas high-risk innovation programmes do not. That risk adversity – pervasive throughout government – is the single most important barrier towards realising more ambitious, more holistic, and more inclusive climate change policy in New Zealand.

Here is a radical fact: elsewhere in the world, since the 1980’s various countries have successfully trialled an entirely different and far more ambitious policy strategy, which for the purposes of this article I will call ‘Innovation Policy 2.0’.

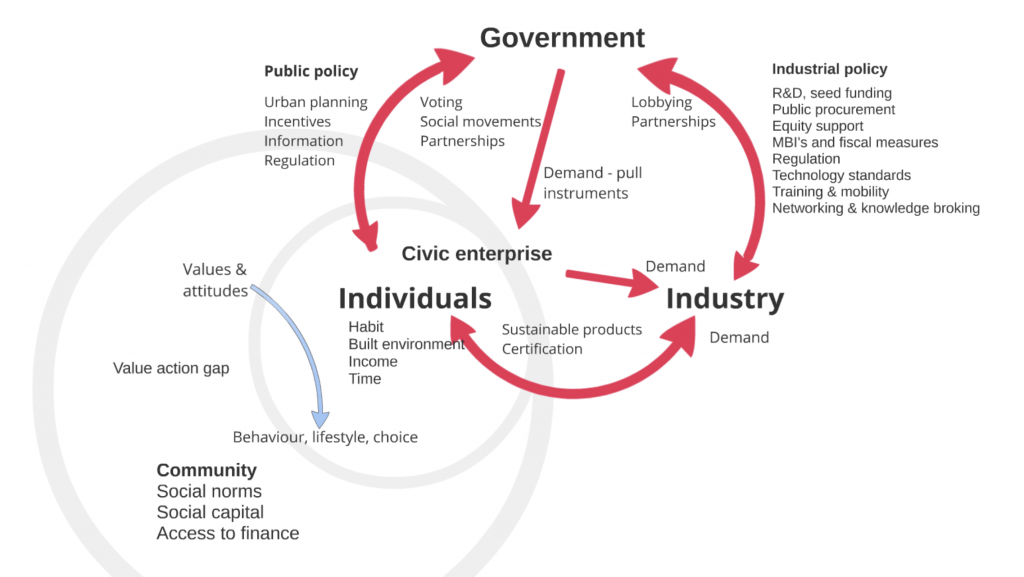

It involves consensus-based sectoral decarbonisation strategies, and targeted funding for low carbon social and technical experiments to successfully test and scale pre-commercial technology and new technology applications, involving a wide variety of start-ups, local firms, community and consumer organisations, and universities.

It involves regional planning and coordination by local government, embedded into national strategies, where local policy entrepreneurs facilitate routes to market.

It involves an open recognition that consumers, consumption and demand-side policies should and can complement market-driven supply-side technological solutions, and that intelligent and patient subsidy programmes can more than pay for themselves as a low carbon industry develops over time.

Applied to New Zealand, it would involve giving every kiwi opportunities to invest and participate in a wide variety of local, regional and national low carbon initiatives.

This kind of thinking has always sat uncomfortably for many kiwis, especially those scarred by the aftermath of Muldoon’s Think Big era. The shift from Innovation Policy 1.0, involving individual choice and market-driven technology diffusion with a dot of supply push policy, to Innovation Policy 2.0, involving inclusive innovation experiments with a different risk calculus, is substantial.

There is mounting evidence that Innovation Policy 2.0 works; we now have solid evidence that effective policy is stable policy, because low carbon industries take up to 30 years to mature. Policy stability arises from cross-party consensus following from widely popular climate change policy, and from pre-empting and eliminating distributional effects of policies through recycling of carbon taxes, levy’s or emissions allowance auctions.

We can never achieve Innovation Policy 2.0 in New Zealand on the back of current stakeholder engagement practices, which rest solely on exclusive invitations to prominent industry groups, roadshows and public consultations in the form of written submissions.

Instead the government needs to come down to the people, not to validate their thinking but to co-create climate change policy experiments, and empower regional and local governments and policy entrepreneurs to do so on their behalf. Deeper public engagement in the form of citizen panels, advisory groups, citizen jury’s or assemblies generate a sense of ownership, and give more attention to the co-benefits and distributional effects of policies and programmes, resulting in better outcomes and broader public support.

Deep Public Engagement

Take for example France’s Convention Citoyenne Pour Le Climat; this involved selection of 150 citizens by sortition to submit legislative and regulatory proposals on transport, food, consumption, work and production and housing in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030. Participants were randomly selected to have the same gender, age, qualification, urban-rural and geographic area make up as French society. They are supported by fact checkers, public law experts and thematic experts.

Can New Zealand channel its crisis response to embark on a more inclusive and ambitious policy strategy?

Can we begin to build a 2 meter low carbon economy that leaves us better off – whatever the outcome of ongoing vaccination trials?

If we connect the dots, stimulus should target three main areas:

- Rather than prop up sectors that struggle to meet 2m social distancing requirements or are affected by international travel restrictions for the foreseeable future – invite them into a targeted transition management strategy that enables strategic future investment – think matchmaking, temporary employment by government and retraining. The government’s $124m investment in recycling infrastructure under the Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund is a promising start.

- Sectors that can feasibly meet 2m social distancing requirements but still struggle can be supported through ICT investment and regional coordination. In this category there are a wide range of businesses including medical centers and pharmacies that can improve their 2m or virtual customer engagement.

- A number of areas that will continue to see growth under the crisis include ICT delivery, online retail and virtual health. Government can support growth and employment in these areas through business development, training and employment.

When citizen voters think of how the government spends public finance, we should be thinking in terms of costs and benefits over the next 100 years. After all, our children will for the most part be paying off the debts from this crisis. The least we can do is leave them an economy equipped with the assets and skills that can generate opportunity from the multitude of environmental and social risks they will be facing.

Come this election, ask your candidate what policy strategies they will pursue to decarbonise the economy that can simultaneously deliver domestic capability and socio-economic opportunity. Make sure your candidate of choice believes we can do it, and that we are good enough.

| Jobs at risk for the foreseeable future | Areas in need of public investment & enabling policies |

| Airlines

Non-essential travel services Sports Personal care Food services Hotel industries Tourism Music and Arts |

Plant-based plastic substitutes

Remanufacturing and recycling technology Energy efficient housing Transport electrification Regenerative agriculture Railway infrastructure Public transport Bioenergy Community energy |

Leave a comment