In a factory at Rolleston, near Christchurch, the future of the way we build houses in this country is up for grabs. Known as the ‘Concision’ plant, it’s a suitably vast edifice for such an ambitious project, 4,500 square metres of working space, with two assembly lines running the length of the floor, controlled by millions of dollars worth of precision German-built equipment. On a February morning several weeks before its official opening, as rain beat against the iron roof, the factory hummed not with machinery, but anticipation.

A $14 million joint venture between onetime rivals Mike Greer Homes and Spanbild, the Concision factory will manufacture panelised walls at pace, and to within 1.5 millimetres in accuracy. Once delivered to site, the expectation is that this shell will be erected and made weather-tight within a day, with the building process done and dusted in six weeks.

General Manager Dave Scobie describes the Concision venture as “an evolution not a revolution”, but it could prove more galvanising than that description suggests. “Personally,” he says, “I believe methods like this are the only way New Zealand can possibly make enough houses to meet demand, because we’ve got ourselves into such a pickle.”

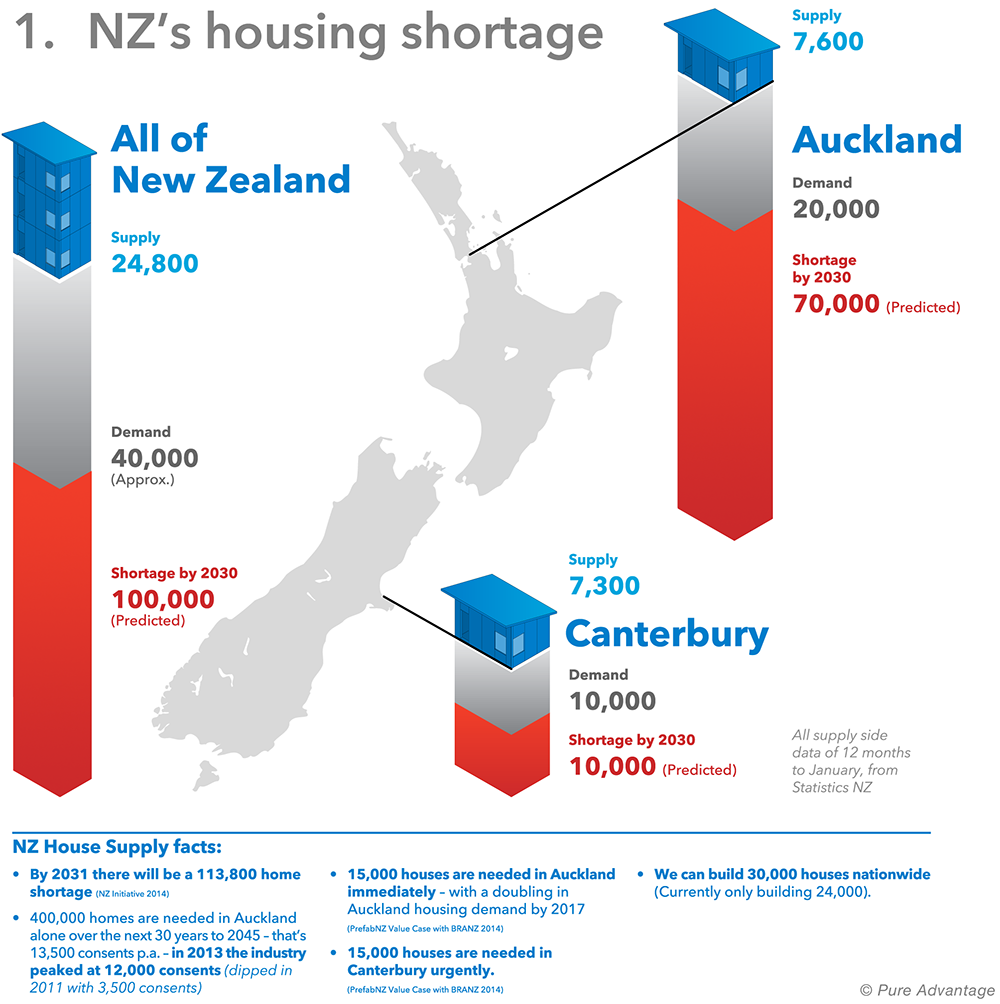

New Zealand is facing a housing crisis, with Auckland and Christchurch at the sharp end. Our largest city has become severely unaffordable, with a median house price of more than eight times the median household income. Strong migration exacerbated by the effects of a construction sector slowdown during the years of the GFC is putting huge pressure on the industry, with 20,000 houses needed in Auckland immediately just to address the backlog. If predictions of a doubling of demand for residential housing by 2017 turn out to be correct, then 9,200 new houses will be needed each year in Auckland, a 53 per cent increase on the current rate. Meanwhile, Christchurch, where almost as many new houses are needed, is dealing with a significant skills shortage and its own affordability problems, amid warnings that shoddy quake repairs will come back to bite.

In combination with the burden imposed by tougher earthquake regulations and leaky homes remediation, Auckland and Christchurch are forecast to drive unprecedented national construction demand through to 2018, with at least 10 per cent annual growth during the next few years. It’s the biggest building boom New Zealand has experienced, a ‘Wall of Work’, and it’s making many people nervous.

Can we cope? The New Zealand building industry’s track record suggests not. According to the Productivity Commission, construction productivity has barely moved the needle during the past 30 years. Systematic inefficiencies in a landscape dominated by smalltime operators, a risk averse culture and substandard skills are the characteristics of an industry caught in a rut. In such circumstances, it’s entirely likely that the pressure of rising demand will result in corners being cut.

In fact, recent Government inspections of quake repairs on 14 houses in Christchurch found significant defects along with issues of building code compliance. The Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (MBIE) has since launched a broader investigation into repair quality.

Part of the answer lies with greater adoption of prefabrication. That’s been the argument for some time from advocates such as non-profit industry association PrefabNZ, and green growth thought leader and advocacy group Pure Advantage, which last year sent out a Request for Expressions of Interest to get a better understanding of the capacity and capability of the New Zealand prefab sector.

“We see an opportunity to reduce the cost of building houses in New Zealand, and to get them built more quickly,” says Pure Advantage trustee Phillip Mills. “There’s also huge opportunity when using prefabrication methods to build sustainably, and to insure that you’re building well insulated, low energy homes.”

Increasingly, the case for prefab is now being voiced at government level and by industry players, with suggestions that some household names in the construction sector are taking a serious look. There’s a sense that the planets are aligning for a new approach to building houses, that business as usual won’t cut it, and that a manufacturing mindset needs to be brought to bear.

It’s an attractive theory. But there are questions about whether the prefab approach that has become de rigeur in countries such as Sweden will work here. Is there an appetite among New Zealand house buyers? Would it make a difference to price and quality? Is the market big enough to sustain anything other than the traditional kiwi ‘stick build’ approach? Underlining doubts, in early 2015, Auckland-based house panelisation firm eHome, which has pioneered automation in panel manufacture in this country since it was founded two years ago, went bust.

That story still has some way to run, with several parties reportedly interested in buying the firm or its machinery. But somewhere between the difficulties of eHome and the fresh hopes for Concision lies a solution to our over-priced, poorly built, undersupplied housing stock.

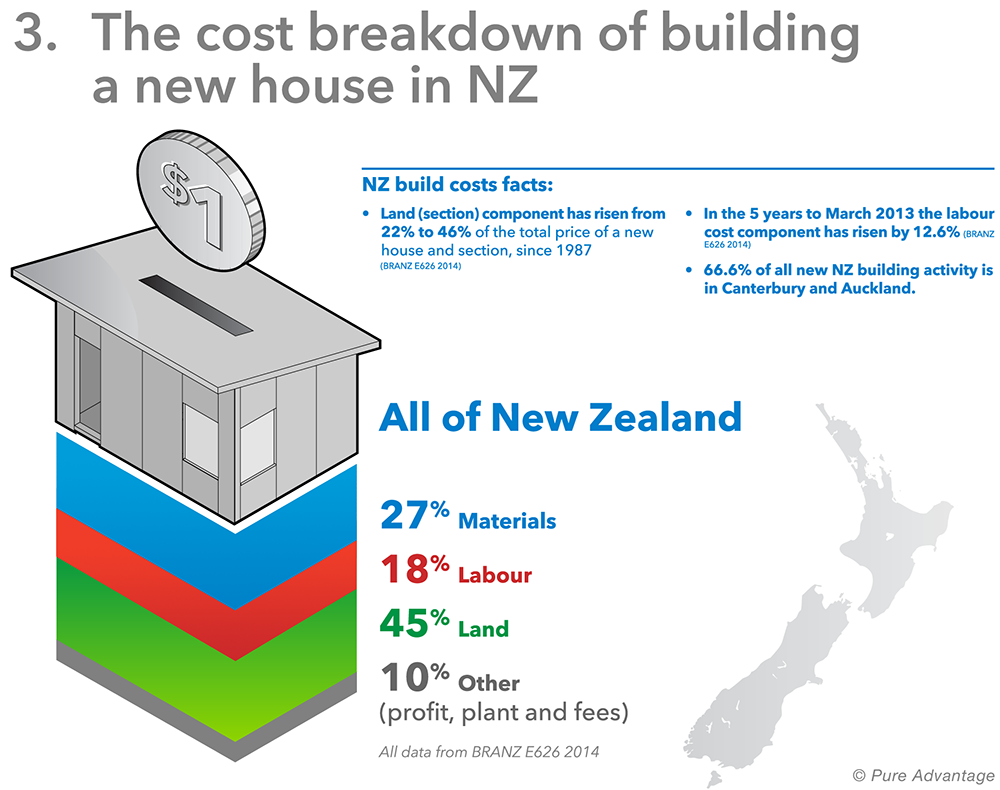

Shamubeel Eaqub is Principal Economist at the New Zealand Institute for Economic Research (NZIER) and co-author of Generation Rent, a new book inspired by his personal experience of Auckland house price unaffordability. He argues that New Zealand’s housing challenge is, by and large, about Auckland, and that the Auckland story is primarily about the cost of land. Within that larger interpretation, however, he sees scope to attack the problem from the other end, by introducing greater use of prefabrication and other building efficiencies.

When Eaqub investigated the relative performance of the New Zealand and Australian construction industries for the Productivity Commission in 2011 his findings weren’t heartening. Labour productivity on kiwi building sites was much lower than across The Ditch, and the trend was worsening. Other research suggests that the construction industry has also done poorly relative to other New Zealand industries during the past 30 years, contributing to rising costs and poor quality building.

“There’s a great deal of inertia,” he says. “The big story for New Zealand in terms of productivity is scale and distance. The construction sector here is very isolated. We have a small, fragmented industry and we also struggle from small market problems.”

If the New Zealand industry could somehow match Australia’s productivity, he suggests, building costs here could be cut by as much as 20 per cent. “It’s that big.”

Eaqub argues that the only prospect of making such an improvement lies with greater uptake of prefabrication. The opportunity is there, particularly in Auckland with ongoing demand for new housing.

“My feeling is that we are already started on this path of more prefabrication, with panelisation, frames and trusses, and so on. As the cost of upfront capital comes down, we are going to see more of it. But it’s almost like someone needs to break the mould – which is why I’ve been so pleased to see the Concision venture.”

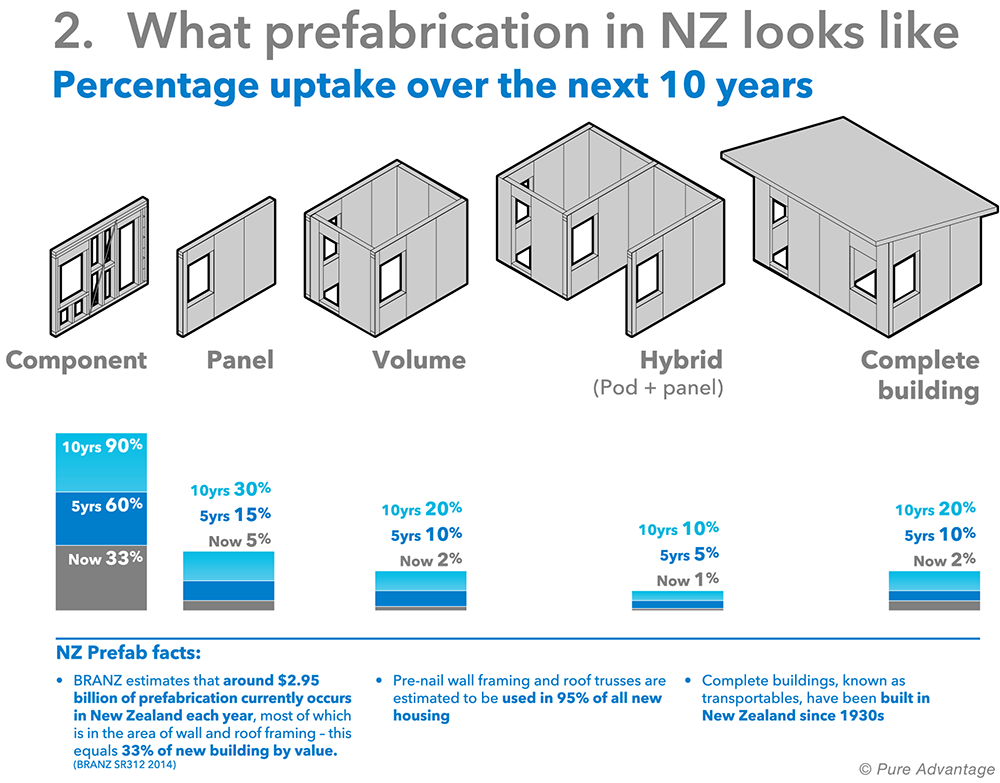

A little background is helpful here. As Eaqub suggests, we already do some form of prefabrication in New Zealand – have done for decades, in fact, from railway cottages, to Lockwood homes, to school buildings. More recently, the building industry has overwhelmingly taken up prenailed frames and roof trusses. According to BRANZ, the association for building research in New Zealand, around $2.95 billion of prefabrication occurs here each year, most of it in wall and roof framing.

But it’s piecemeal. Until a revival of interest in the new millenium, there was never consistent enthusiasm among builders, architects and engineers for the idea that a house, or even many of its components, can be treated as a manufacturing exercise, prefabricated in controlled indoor conditions then assembled on site. New Zealand house buyers, too, have traditionally been averse to prefabrication for anything other than baches, associating it with ticky tacky-housing and temporary building solutions.

Other countries are far more advanced in their uptake of offsite manufacturing. In North America, up to one third of all new family houses are modular or manufactured. In Sweden, the uptake is 74 per cent, driven by demand for energy efficiency and sustainability. Far from being associated with cheap-and-nasty, prefabrication in some of these places is now synonymous with quality.

It’s a point stressed by Pamela Bell, founding CEO of industry hub PrefabNZ and co-author of Kiwi Prefab: Cottage to Cutting Edge. Her organisation’s Value Case for prefabrication, produced with BRANZ and the Productivity Partnership last year, claimed that greater use of prefabrication can remove $25,000-$40,000 from the cost of a standard home, mostly through time savings. But its primary case rests with international research that prefab is a higher quality option.

“The number one advantage to using more prebuilt parts is about controlling quality, because you can do that better indoors than on site,” says Bell.

It’s a potent argument at any time, given our history of building poorly insulated, inefficient and often plain unhealthy houses. But the looming ‘Wall of Work’ scenario makes it particularly compelling.

Bell suggests we’ve arrived at a tipping point. Given the concerns about productivity, the industry is warming to using more prefabrication, she says. It has to be, really. “It isn’t geared up to respond to leaky buildings, the Christchurch earthquake and the Auckland housing shortage. We simply can’t deliver the housing needed at one house per builder per year.”

“The industry is also interested at a strategic level in increasing the value that clients get, because there is that typical ‘Takes twice as long, costs twice as much’ thing that just drives clients bonkers. Prefabrication basically means that a lot more stuff happens in the planning stage. The result is that the consumer ends up with a known quantity: known quality, known timeframe, known costs, sustainability and design.”

She suggests that the way forward is to slowly augment the amount of prebuilt componentry used in a typical house. “The supply chain is highly polished in certain segments of traditional building, which is why I think that the thing for prefab is not to propose that houses come fully formed on the back of a truck, but rather that the frame and truss component that everyone is already familiar with just comes to site slightly more enclosed. There’s enough involved in the transporting and handling of something like that to create a fundamental shift in the way that builders assemble houses.”

Isn’t that a watered down version of prefab? “Not at all. Every step of the way we are talking about increasing quality and reducing time – and reducing the risks for the client.”

Finding a version of offsite construction that fits the idiosyncratic New Zealand setting is key, says Nikki Buckett, a building science advisor for the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). In a previous role with BRANZ, Buckett investigated the potential of several alternative building techniques to address the criticisms of poor productivity, quality and value for money in the building industry. Her 2013 report, Building Better, concluded that panelised offsite construction offered the most hope.

As part of her research, Buckett spent time in Germany, where large panelised offsite construction firms can manufacture houses in hours, with a fortnight’s finishing on site. Adopting overseas models holus-bolus isn’t feasible, she says, but there are elements that could easily work here.

Buckett cites benefits such as tighter quality control, improved value for money and shorter construction timelines. There are also definite sustainability payoffs if a factory is set up correctly. “It’s about efficiency, maximising the use of materials, minimising waste and the resources used on a house.”

The waste argument is a strong one. Around 40 per cent of New Zealand’s landfilled waste comes from construction, so any minimisation at the building site will have an impact. In the US, the modular house industry achieves waste levels of just two percent, a massive improvement on traditional methods. (Prefab doesn’t have a monopoly when it comes to reducing waste, of course; the Homestar rating system, for example, includes tight waste management requirements). By using optimisation software and high-precision machinery, a panelisation factory can maximise the use of materials. And by building offsite, you reduce the risk of timber treatment chemicals leaching into the environment, not to mention transport needs.

In this case, what’s good for the environment is good for the budget, says Bell. “Once you get into a commercial multi-unit residential development, if you are saving even one per cent of construction costs through waste minimisation that makes a big dent on the bottom line.”

There is growing acceptance of these arguments by government, according to Chris Kane of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). Kane is Manager of the Productivity Partnership, a collaboration between the ministry and the building industry to address poor productivity. Among its first tasks on forming in 2010 was to hunt out inefficiencies in current construction systems.

“One of the big ones was weather delays, which accounted for 20 per cent of time lost, but there were other systematic inefficiencies,” he says. “The work kept pointing towards offsite prefabrication, some way of industrialising the process rather than everything being bespoke and last minute. Prefab at its roots is about decent process control, getting a grip on what you do and making it reproducible.”

Like others, Kane stresses that prefab is no silver bullet to the problem of unaffordable housing. “It may have an effect, although not the immediate one you expect. By using production methodology you remove some of the variables, so the price of a house starts to become more fixed, and that will eventually have a knock-on effect.”

“But the benefits play out more in quality,” he continues. “For the homeowner you get a more reliable product. You don’t have doors that need unsticking after three months; you get cabinets that fit properly from day one. Think about what the Japanese did with cars – the ratcheting up of expectation drags everyone along.”

Leave a comment