It’s a scenario that kiwi homebuyers should welcome: factory accuracy; a quick, water-tight build; known costs and qualities. But there are some sizeable barriers to be addressed if prefabrication is ever to become an integral element of our building scene.

For starters, prefab has a serious image problem in this country. “The historical misperception is that it’s cheap, that it sits on the back of a truck, and that it’s only intended to last a short period of time,” says Pamela Bell. “We’re having to work hard to reorient industry, public and government perceptions.”

Overseas examples suggests that it’s not impossible. Johann Betz, principal of Christchurch-based Offsite Design, has a background in panelised prefabrication and timber engineering in Europe. “When panelisation started off in Europe, they made cheap, flimsy buildings, and it established a poor reputation for prefabrication,” he says. “To save their industry, there was a huge focus put on quality. The industry was transformed [through quality assurance standards] and now a prefabricated home is almost a status symbol.”

Another problem: New Zealanders are in love with bespoke houses. “We have a highly customised housing stock in New Zealand,” remarks John Beveridge, a former CEO of PlaceMakers and now a Director of Design Windows Group, a prefabricated window manufacturing business. “We have very little standardisation. Every window requires onsite measurement, and it’s the same with the roof and a lot of the other components.”

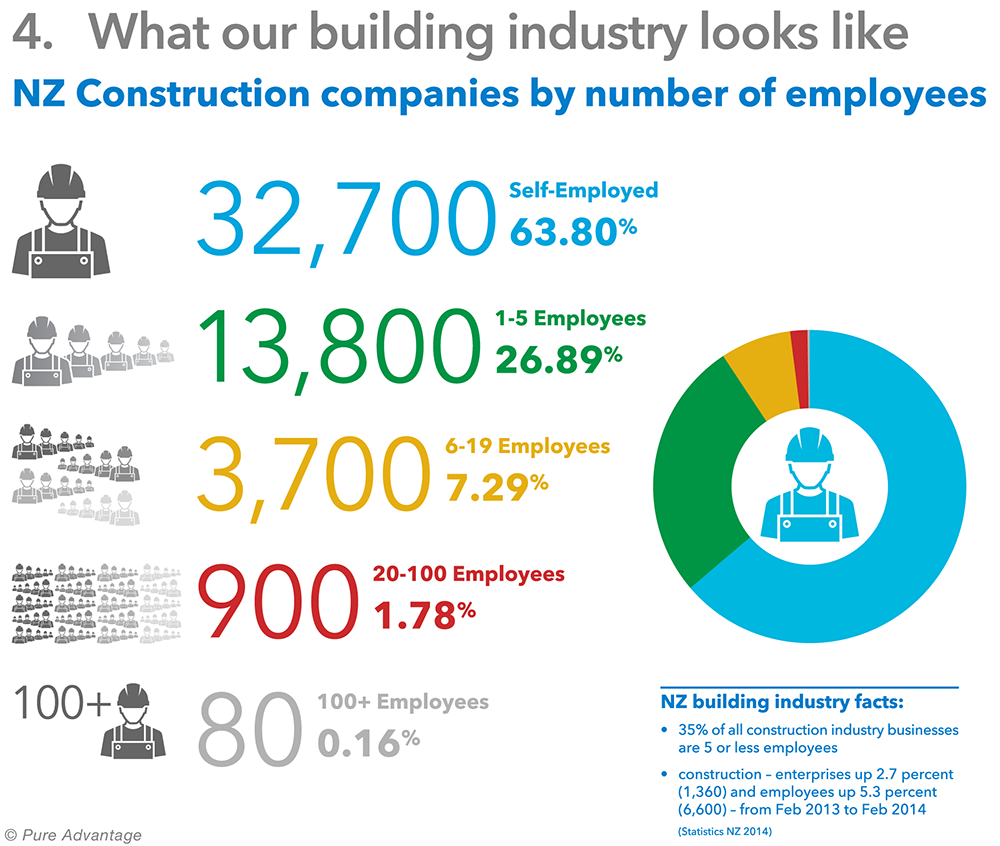

Even if the perception issues were overcome, is our building industry capable of delivering? More than 90 per cent of kiwi house builders are smalltime operators of five employees or fewer, and more than half of those are one-man-bands.

“They don’t have much capital, they work with tools that aren’t particularly expensive, and it’s a lot easier for them to order components from a supply merchant and assemble them on site,” says Beveridge. “A factory process requires organisation, capital and scale, so that’s a big challenge for prefabrication in New Zealand.”

There’s a possibility, too, that the current boom might work against innovation. In busy times, builders may just want to “crank the handle” using tried and trusted methods, says Chris Kane. “Business skills in the industry aren’t as developed as they should be, and it’s a problem. We’ve seen a dramatic change in the primary industry, where farmers have gone from running a family business to running an internationally competitive one. But we won’t create an industrialised, systematic base [for building houses] until we get that same business acumen being applied to residential construction.”

Unlike Europe, New Zealand also lacks volume customers who might demand a certain way of building. “We need intelligent customers who aren’t just wanting to buy 30 houses, but 300 houses, or 1000 houses,” says Kane. “At the moment the incentives in the system and the way procurement is often done militate against that. Rather than taking a more planned approach to things, it is really all about cash flow.”

Getting developers on board is key, he argues. But it will be a tough ask: in the property development game, building fewer homes at the higher end of the market tends to offer more attractive profits.

Wellington business consultant Murray Wu investigated the prefabrication sector while in a previous role as General Manager Corporate Responsibility for Kiwibank. “If you look at all the players, the developers, construction sector, the people who sell homes, where is the bottleneck? It’s the developers,” he argues. “People say you have to persuade consumers, but my feeling is that comes later. Right now the barrier is on the supply side.”

Risk aversion is in play. Prefabricating housing is unfamiliar; there’s no well beaten track. “In the commercial sector in New Zealand prefab is easy, because you have a well-established supply chain,” says Bella Franks, an Auckland-based structural engineer with architecture, engineering and construction firm Aecom. “You have concrete precast yards, seal manufacturers, pre-engineered connections for pretty much everything. But in residential construction the [prefab] supply chain isn’t understood. As an engineer, I wouldn’t know where to start if I was given 100 houses with all the detail. Modular? Panelised? I wouldn’t know who to approach.”

Beveridge is categorical. “It’s going to take the big guys getting involved in offsite manufacturing to make it work, and it has to be an end-to-end thing. The builder has to design it, develop the land, build it and hand the keys over to the buyer. We really need the likes of Fletchers to be doing this.”

It may yet happen. At presstime, Fletchers was understood to be a leading contender to buy eHome.

Whatever happens with eHome, the opening of the Concision factory is a major shot in the arm for prefabrication’s prospects.

The massive sum invested is obvious when you visit the Rolleston plant. From the start point, where a gleaming German Weinmann saw cuts the timber under the guidance of optimisation software, to the second station, where cut timber is gripped in jaws and indexed precisely to the next stud, to subsequent stations, where plaster-board is cut, glued and screwed, bats are installed, and heavy duty chipboard nailed down, it’s an exhibition of efficiency and accuracy.

That accuracy is critical. Concision will be turning out 12 metre long wall panels, to arrive on site pre-lined, pre-insulated and pre-clad. There’s no way to make them fit if they’re out of whack. “I’ve still got a lazy thousand bucks for any builder who says they can build a house to plus or minus 1.5 millimetres,” remarks General Manager Dave Scobie with a grin.

Take window openings. Traditionally, these have to be measured on site, and builders often use packing to make things fit. “Because our process is so accurate we can order the windows off the plans. There’s a time saving involved: at the moment in Christchurch there is a three week delay between onsite measurement and installing on site. And when we install those windows we don’t have any gaps.”

The other great benefit is speed of assembly, with Concision aiming to make a house weathertight within a day. Recently, someone built a house down the end of Scobie’s street. He watched the frames being delivered to the site, shortly before the rain arrived. “It rained for the next week and those frames were sodden. I just know that house is going to have problems. We are going to have none of that.”

It’s an impressive operation. But looking beyond the gleaming machinery, can Concision make an impact on the building scene?

At full capacity, the plant will be able to produce two smaller houses per shift, or one larger house of 150-200 square metres. The expectation is to produce 600 houses a year, split evenly between Mike Greer Homes and Spanbild, mostly destined for the Canterbury market. In the scheme of things, it’s not a massive number.

Yet it could be a catalyst for wider change, according to Peter Freeman, the “special projects” boss at Mike Greer Homes who did the feasibility investigation on Concision. He says owner Mike Greer, a chippie by trade, has his eye on the bigger picture.

“Mike was looking at what he could do to improve building in New Zealand and make it more cost effective. He looked at other forms of construction, but he came back to [offsite panelisation] as being the most flexible, the highest quality and the best fit for the New Zealand market.”

“The machinery that Mike and [ Spanbild owner] Bill Gee bought, for example, wasn’t the cheapest, but it had the tightest tolerance and was flexible, too – because we don’t want to do just cookie-cutter housing. Every house that comes out of the plant can be completely different.”

Will it produce more affordable housing, though? Yes, answers Freeman, although it’s too early to say how much might be saved on the build cost. He notes, however, that a speedy, six week build time should deliver additional benefits. “There are client savings to be gained in terms of servicing loans on the section, and on the cost of rent while your house is being built or the cost of paying two mortgages.”

There are bigger schemes afoot. Greer and Gee want to create a second Concision plant near Auckland, to supply panelised homes into the greater Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga markets. It’s understood that they are interested in the eHome business, but have also looked closely at building a new factory on a site in Pokeno. Greer has said that it could eventually produce 1250 houses a year.

Where’s the market for prefab? Given the housing shortage, that sounds like a redundant question. But capital intensive ventures such as Concision need to be running at close to full capacity to thrive.

Scale is key. Chris Kane suggests that a “sweet spot” for offsite manufacturers could be midscale multi-residential buildings – three to four storey walkups, for example. “These are developments that are bigger than most residential builders could handle, but smaller than most commercial operators would want. That’s where there could be an opportunity, I think, an optimum of density and scaleability.”

John Beveridge believes the retirement village industry is potentially another key customer for prefabrication. Bathroom pods, for example, could be rolled out en masse. “Some of these retirement village companies are very efficient operators who repeat the same design for village after village.”

According to Pamela Bell, PrefabNZ is working with Community Housing Aotearoa and the Retirement Village Association’s members to tally future building requirements, with an eye to prefabricated solutions. “It’s about getting all the need in one visible pipeline,” she remarks. “Instead of saying ‘That social housing project needs five bathroom pods’, imagine having 300 pods to prefabricate across the sector over two years. That’s when you’d start getting some good efficiencies.”

She predicts that prefabrication will also feature increasingly strongly in leaky building remediation. “There are a lot of time savings from using prefabricated cladding and other solutions such as prebuilt roof sections. That’s important when you are rehousing people who have large multi-unit buildings that need remediation, or difficult site constraints such as wall paneling adjacent to another building.”

What about social housing? Brian Donnelly, Executive Director of the New Zealand Housing Foundation (NZHF), believes offsite manufacturing is part of the answer to Auckland’s housing woes. And he’s put his money where his mouth is: the Foundation used eHome as one of three builders on its Waimahia Inlet affordable housing development in South Auckland.

But Donnelly believes better design might have even more impact on keeping house prices in check. We build unnecessarily big houses in this country, he says. “I know that eHome has done a lot of good work on house plans, cutting out every inch of unnecessary floor space. But our wider architectural and design industry is not flash in that regard.”

Beveridge agrees. “One way of getting the cost of housing down in New Zealand is to build smaller houses, to make more efficient use of space. And once you start down that road you probably want to be doing it in a factory. That’s what happens in Asia and Europe – smaller spaces, better designed, and involving factory precision to assemble. That’s definitely going to happen in Auckland. We are going to end up with smaller living spaces, requiring better design and more precision building to get everything to fit.”

In fact, prefabrication’s future is closely tied to the argument for greater intensification in our cities – and to questions of urban design. “Prefabrication needs to be understood at the level of the city,” says Wellington architect Chris Moller, who has worked on prefabrication-based social housing projects in Europe. “It’s important we don’t say ‘Oh, prefab is easy, we’re already doing it with trusses and pods and panels’. If you keep putting those solutions into the old typologies then you’re not going to reap the real benefits.”

Prefab shouldn’t be about one-off suburban houses, Moller argues, but about terraced housing and low-rise multi-residential developments. “You can maximise its benefits by fabricating solutions that involve sharing walls, sharing energy, sharing insulation, and so on, all of which work to drive down costs.”

Scenarios of infill and intensification could be tailor-made for prefab, reckons NZIER’s Eaqub. “If you look at the geography of Auckland … it will have to be more volumetric, component-based solutions. But it’s an opportunity for prefab. Having building projects take less time and involve less disruption is a [selling point].”

Christchurch in rebuild mode could certainly benefit from the speed of prefab. “For existing neighbourhoods who don’t want to live in a 30 year construction zone, it’s really important,” says Bell.

There are big changes ahead if prefab is to take hold, not least of mindset. The way buildings are typically delivered in New Zealand is linear: architect to manufacturer to builder to client. Prefabrication, however, is collaborative, with all parties involved from day one.

Can the industry adjust? History suggests it won’t be easy, says Bell. “In terms of cultural change I’ve heard people say the construction industry is slow. The supply chain and the building process are so engrained, and prefabrication requires you to rethink the whole process. You can’t just pass a design on to the builder and say ‘here you go’. But collaborative upfront processes always have better outcomes over the building’s lifecycle – and better financial outcomes.”

Builders aren’t the only ones needing a rethink. “Prefab doesn’t fit with people’s expectations of cash flow – the customer would need to pay substantially up front,” says Kane. “Insurance companies don’t get it. Another question: who offers the warranty? And when it comes to consenting prebuilt parts, councils are asking ‘Is it building work? A product? What is it legally?’.”

So what’s the way forward?

Smoothing the compliance path is critical. Kane says MBIE is close to releasing guidance to help Building Consent Authorities deal more confidently and swiftly with manufactured building solutions. In the same vein, the ministry wants to make it easier for innovative alternative construction solutions of all kinds to get the tick from BRANZ.

“From where we are sitting, the most effective thing we can do is to simplify the navigation of the system, to declutter it.”

But while it’s new and challenging now, he says, prefabrication has intrinsic potential to speed up expensive consent processes. In some countries, building authorities monitor a prefabricator’s quality assurance system rather than tick off the individual finished product – in other words, they check the car factory, not the car.

A draft of the forthcoming guidelines paves the way for this streamlined approach, recommending a smart consenting approach for applicants involved in offsite manufacturing.

Another task is to rehabilitate prefab’s image. PrefabNZ is leading the charge there, with initiatives such as the Home Innovation Village (HIVE) in Christchurch, which showcased prefabricated ‘eye candy’ such as architect Andre Hodgskin’s ‘Park Terrace’ for Keith Hay Homes.

For Bell, greater uptake of prefab is not so much a question of ‘if’ but ‘when’. “In the not-too-distant future we won’t even be talking about prefab or offsite,” she says. “These processes will be invisible, seamlessly integrated into traditional construction much like trusses and frames are today. Prebuilt parts will become just another tool in the toolbox, used to deliver a home on time, on budget, to the desired level of sustainability and design.”

-ends

Read more about how offsite manufacturing leads to healthier homes.

Terminology:

What’s in a name? If you’re seeking to rehabilitate the image of prefabrication quite a lot, it seems. In essence, prefab simply refers to on-site assembly from prefabricated components. But in New Zealand the term is tarred by historical association with cheap and impermanent buildings the draughty temporary classroom at school, the flimsy bach. No wonder that some proponents are leery of even using the term, preferring ‘offsite construction’, ‘offsite manufacturing’, ‘prebuilt’ or similarly less loaded terms. However, in this article prefabrication is used for simplicity’s sake.

That said, the term prefabrication encompasses various degrees of completion offsite, a continuum that starts with prenail, and ends with a fully finished house being trucked to site. So, some definitions are in order (with thanks to BRANZ and PrefabNZ).

- Component prefab. Lowest level of prefabrication, creating components out of materials to increase speed onsite. Example, precut framing.

- Panelised or panel-based prefabrication. This involves planar units such as walls, floors and roof panels, and may include windows, doors or integrated services. Once delivered to the building site as flat-packs, essentially involves assembling two dimensional “area” elements.

- Volume (or modular). Structural boxes or modules erected offsite and brought together onsite to form a complete building.

- Hybrid. Combination of one prefab method with another, or with traditional construction. Example, modules interspersed with panels.

- Transportables. Complete building constructed offsite.

Leave a comment