Local government – are they just providers of basic public services, or are they guardians of their communities’ current and future well-being? Depends who you ask. The present government sent a strong signal back in 2012 when they amended the Local Government Act (LGA) to describe the purpose of the sector as ‘to meet the current and future needs of communities for good-quality local infrastructure, local public services, and performance of regulatory functions in a way that is most cost-effective for households and businesses’. The concept of ‘sustainable development’, formerly front and centre, was relegated to a latter clause and references to ‘wellbeing’ were replaced with ‘interests’ instead. Ministers said local government had overreached themselves citing examples which, on closer inspection, were dubious at best. Of course, the Act’s new wording leaves massive leeway for interpretation, but the Government’s message was clear enough: pull your heads in.

But there are issues that are too big to ignore, and climate change is one of them. When a town is hit by storms or flooding, it is the local Council at the front lines of the emergency response and takes a large share of the burden for sorting out the mess afterwards. Councils are responsible for spatial planning, local road networks, storm water, waste management, water supply and an asset base with a significant carbon footprint. They are directly accountable to the public, rather than shareholders. Although it is tempting for elected members to put difficult decisions off to another day (or preferably, to another set of anonymous councillors in the future) in the long run there is nowhere for local government to hide from these responsibilities.

The Paris Agreement makes this clear, stating that parties agree to ‘mobilise stronger and more ambitious climate action by all parties including… cities and subnational authorities’. At the end of the Paris talks over 7,000 cities and regions had committed to cutting carbon emissions through local actions. These commitments are formalised and monitored through the global Compact of Mayors, which within New Zealand, Auckland, Wellington and Dunedin are part of. In addition, thirty-one New Zealand local authorities are signatories to the 2015 Local Government Leaders Declaration on Climate Change, which says they ‘commit to develop and implement ambitious action plans that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience within our own councils and for our local communities…’. Fine words, which indicate the local government sector knows it can’t sit on the sidelines. But where can these words translate into action? What is stopping them from showing the dynamism on climate change that many New Zealand businesses, large and small, already are?

What councils can do

Councils make their spending and activity plans on a three-year cycle, looking 20 years ahead at least. The next cycle is for 2018 – 2021. They would do well to read the NetZeroNZ report closely when formulating these plans. They would see drifting along, half-heartedly following technology trends is ‘off track New Zealand’: a pathway to disaster. The report also says that complementary measures to a strong carbon price are essential: local government is well placed to implement these, helping their communities to reap the many co-benefits that would come with them.

Smart investments will reduce costs for ratepayers over those 20 years, even when viewed with the narrow scope of the LGA 2012. Energy efficiency programmes, for example, optimising pumps, improving building system controls and converting their streetlight stock to LED lights are no-brainer measures. However, it takes corporate prioritisation to see such programmes get off the ground, and endure in the long term. EECA can give support for this – for example, they were instrumental in jump-starting New Plymouth District Council’s long-running and award-winning energy management programme – provided the local authority is willing to engage in the first place.

Councils need a strategic overview of their entire emissions profile in order to manage it effectively. The ISO 14064-1 framework is the gold standard for how this should be done to ensure everything that should be included is included, that emissions calculations are robust, and that there is continuous improvement to measurement methods. Recognising this, Kāpiti Coast District, Dunedin City and Wellington City Councils are all ISO14064-1 accredited through Enviromark Solution’s CEMARS programme. Being CEMARS accredited led to Kāpiti Coast to cut its emissions by over 50% in the space of five years, by helping target emissions in its wastewater treatment and disposal processes.

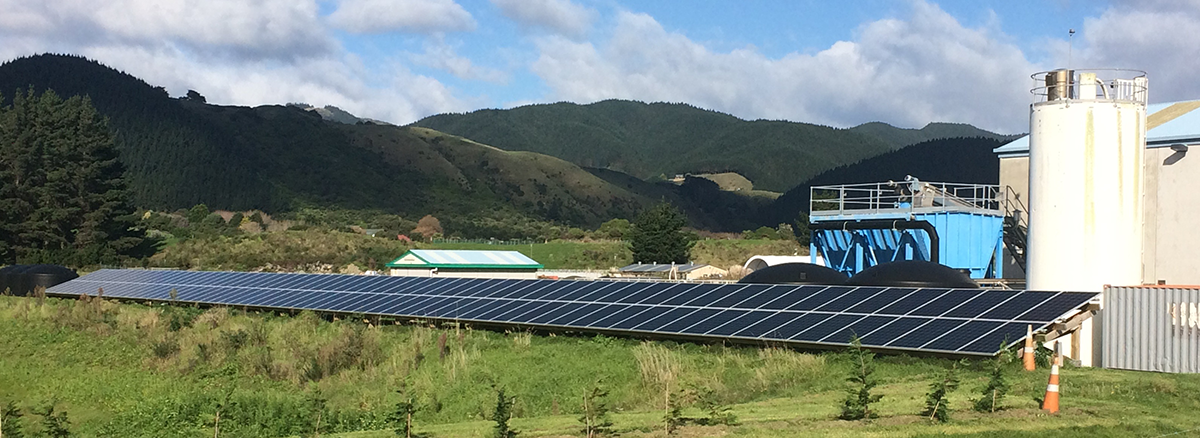

Decarbonisation and electrification, as described in NetZeroNZ, is a strategy that Councils can adopt through the asset renewal processes tied to their long term plans. As roofs need replacing (or even before), there are opportunities to install solar PV. Council facilities like libraries, museums, pools and offices mostly use expensive daytime power, which is offset by solar, and the lifetime of PV-clad roofs are extended as well – music to an asset manager’s ears. Council vehicle fleets are constantly changing, presenting many opportunities to adopt electric vehicles. To ensure such opportunities are not missed due to organisational inertia or personal bias, Greater Wellington Regional Council has introduced an ’EV’s first’ policy. Municipal swimming pools are ideal candidates for electric heat pumps. And so on. Such measures may require additional upfront investment but will serve their communities well in the long run. However, without a strategic focus on emissions, local authorities can easily miss these chances and lock their communities into high-carbon infrastructure.

Kāpiti Coast District Council’s Nissan Leaf EV, part of their car pool.

Councils can help to transition to EVs by providing charging stations at their facilities and in town centres. However, they could easily be caught out by the rapid pace of change if they neglect this in the current round of long-term plans. New Zealand is experiencing an exponential growth in the number of electric cars on the roads. The government target of 64,000 EVs by 2021 is widely expected to be exceeded. Councils are making their plans for 2021 in an environment of relatively few EVs: if they do not make an adequate provision for developing and operating EV charging infrastructure now, they will be scrambling to respond to demand in a few years’ time.

netzeroNZ also emphasises the crucial role land use plays in New Zealand’s emissions, and councils are involved in this too through their spatial plans and environmental restoration work. Afforestation, especially of native species, can bring multiple benefits such as land stabilisation, water quality improvements, flood mitigation, amenity, recreation opportunities, improved biodiversity and in some cases economic opportunities (think of the burgeoning market for manuka honey). All this and carbon sequestration too! The carbon benefit of afforestation can be quantified and even traded via the government’s Permanent Forest Sinks Initiative, but other benefits, despite economists’ best efforts, stubbornly defy such treatment. Once again, this is local government territory: using rates and regulation to bring their communities benefits and protections the market would not otherwise provide.

What’s stopping them

Unlocking the potential of local government to contribute to netzeroNZ means overcoming a few barriers first. One is the aforementioned temptation for elected officials to put off difficult decisions for another day–especially when central government is not putting pressure on them to act, and rates can be kept down in the short-term. Another is the tendency for issues with no long-term or strategic significance to dominate council’s agenda, consuming the available political oxygen. Further, in a largely futile effort to avoid negative headlines (which are inevitable where councils are concerned), councils can get an over-developed aversion to risk, real or perceived. This leads them to become increasingly process-oriented and hierarchical, which stifles the flow of information, ideas and innovation, slows progress and can deter them from making sensible long-term investments. From the outside, this behaviour can seem mystifying, especially to the private sector, who are used to being more dynamic.

So, to return to my headline, the solution is to lead the leaders. Councils are sensitive to the needs of their communities. They can act decisively, particularly in times of crisis. Although climate change is a crisis, they are not getting this message clearly enough from residents and central government. It is up to everyone who does recognise the need for a net zero New Zealand, be they businesses, groups or individuals, to demonstrate popular support for action. They can do this by actively and constructively engaging with council officers and elected members on the specific low-carbon opportunities available to them, and the many benefits they would bring. Given councils are presently preparing their new long-term plans, now is the ideal time to do it.

Leave a comment