In an age before many of us remember – the 1920s and 30s – we were clumsily untangling ourselves from the apron-strings of Mother Britain. Our nation was like today’s twenty-and thirty-somethings who return home for a proper feed, and irregularly and nonchalantly delivering dirty clothes to the laundry-fairy.

A young and hopeful nation we were. We had offered up our best and brightest for the great war a decade prior. In its wake, there came a great rebuilding of nations and the powers that be decided it was time for us (as with many other Commonwealth countries) to mint our own national debit card. What few of us will remember is the clear and pressing issues at hand – we did not have our own currency, manage our foreign exchange or manage our own foreign reserves.

At the time, effective solutions may have been clear to an enlightened few but the government was reluctant. Likely there were many other important social, economic and environmental challenges, but they lacked focus and mandate to act. It was not until the great depression in the early thirties that the government felt a driver powerful enough to agree to the Reserve Bank Act, and open the doors of our central bank. This forward thinking meant that our nation had a vehicle to introduce inflation targeting and independence from political tampering when the Act was amended in 1989.

And what does this have to do with today? Similar to the 1920s and 30s, we have another present-day issue that will challenge our national wealth, our foreign exchange and reserves. The issue will also deeply challenge our identity and how we eke out a living.

The recent Vivid Economics report has described possible ways New Zealand can mitigate our carbon dioxide emissions and meet our commitments made under the Paris Agreement to address climate change. Commissioned by GLOBE-NZ (a non-partisan parliamentary climate change working group), the tweet version of the report is:

However planting trees on its own is just one temporary solution. The cold reality of a change in land use means a sinking lid is applied to land currently used for dairy, sheep and beef farming. How low does this lid go? This varies across the scenarios. Alison Dewes summarised potential agricultural land use change across the three scenarios well in her piece Back the Truck Up.

The report is the doctor’s checkup that we’ve been avoiding. After the check-up, the doctor gently but firmly says, “I’m sorry to say New Zealand, but we need to open you up and take out the bits that are causing the problem, and going forward there are going to be some lifestyle changes – you can’t keep living the same lifestyle and working the same job.”

So, how does a nation reduce its emissions, who gets what in this game of Pass-the Parcel? We know from BNZ customer research that when ranking New Zealand institutions, New Zealanders hold the government responsible first and foremost. Businesses are a close second. However, it will be the businesses that are made either heroes or villains because of their inherent size and scale. It is the government who must carefully set the rules so that businesses have the imperative and clarity to make investment choices that align with addressing our nation’s emissions imbalance. This will be a significant policy challenge, but this is not the first difficult challenge that has darkened the doorway of our government.

The transition will take many decades, and to make good decisions, our local businesses have asked repeatedly for regulatory policy and price stability when it comes to offsetting their emissions. And fair enough too. Evidence of long-term damage from policy flip-flopping across election cycles is close to home just across the ditch. As a result of Australia’s regular u-turns on environmental policy, businesses and financial institutions have become gun-shy about investing in climate solutions. Here in New Zealand, our forestry sector has been hampered by emissions pricing that is considered by many to be too low.

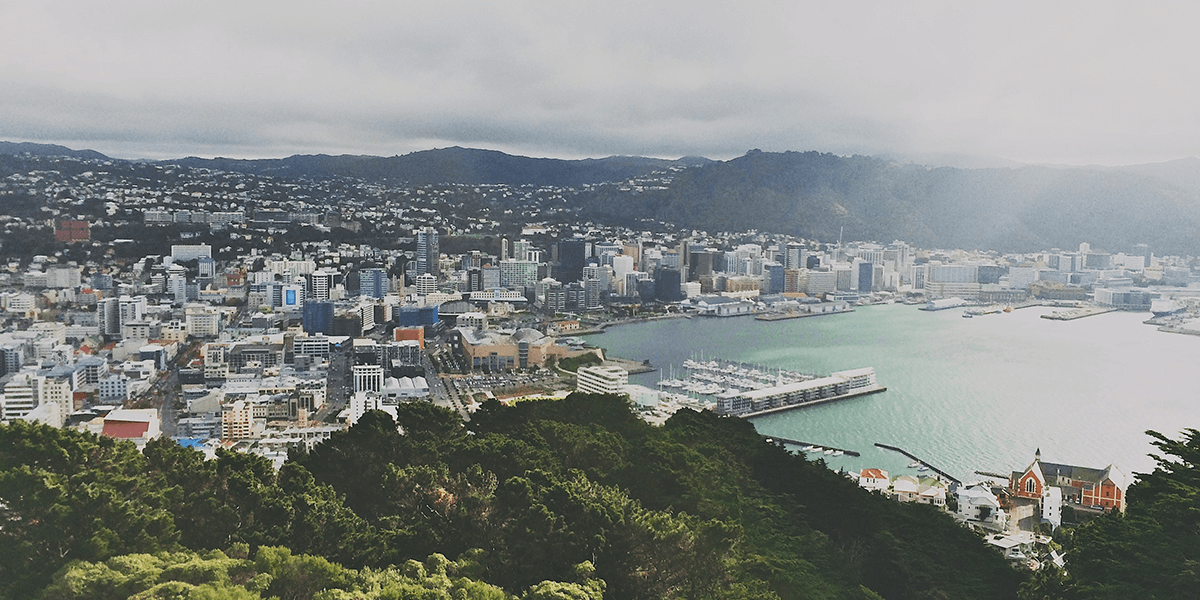

Credit: Chris Davis

Policy and price stability is crucial for business, even more so than the idea of price stability in the Auckland rental that my family lives in. Net Zero New Zealand recommends an independent institution “just as the Reserve Bank of New Zealand helps to anchor investor expectations regarding price stability”. That’s a bit of a mouthful, but currently, we have a plethora of government agencies (MfE lists nine as well as other local government authorities) responsible for addressing climate change. The nugget here is what we can lift and shift from the RBNZ’s 83 years of history to help us stay on the right climate track. The Reserve Bank:

- is independent of the government and has a five-year policy targets agreement – this means it is insulated from political tampering and adjustments around election cycles.

- is responsible for maintaining a moderate level of price inflation.

- is has tools that empower it to achieve this, one of these tools is the official cash rate.

- is responsible for maintaining the stability of the financial system, and has powers to regulate banks and other financial institutions to achieve this.

- has internal capability to model the current state of the economy and inform the development of new tools.

- has a communication function to help the public and business sectors (6) understand the reasons behind decisions.

- can change the official cash rate at any time, but chooses to update the market on a six weekly basis.

The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment has independence (1) but no powers. The current Commissioner Dr Jan Wright and her office are held in high regard, but they have no teeth. The Ministry for the Environment and Environmental Protection Authority currently have responsibility for the policy development and management of the emissions trading scheme (2 and 3), but can they give business the assurance it needs around regulatory and price stability? In short, no.

The Net Zero NZ report specifically recommends an independent statutory climate commission that would:

- identify expected trajectories for the emission prices to help private-sector investors make informed decisions over long-lived investments that reduce the risk of lock-in to high emissions assets and/or the risk of asset stranding

- identify whether there may be tensions between New Zealand’s plans to reduce its emissions and other elements of the government’s economic development strategy

- provide a platform to support ongoing, more detailed scenario analysis to inform New Zealand’s low-emissions pathway planning and support subsequent coordination and implementation

- employ a dedicated body of experts focusing exclusively on climate change and the appropriate policy response to facilitate flexible and adaptive decision-making.

The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Dr Jan Wright has also last month released her recommendations on how New Zealand should enact its own version of the UK Climate Change Act.

Do the findings of the Net Zero NZ report, and the environment commissioner go far enough? Both stop short of recommending that our ‘commission’ have its own powers, remaining only an advisory function. Will a commission that is limited to an advisory capacity give businesses the guidance and certainty that they need to make long term choices? Of this, I have a concern. Management of the ETS, being able to set future term ceiling and floor prices, and other tools must be part of the mandate.

Symbolically, in Wellington, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand sits across the road from Treasury, and diagonally across the road from Parliament. From my old desk at the Reserve Bank, I always wondered why there was such a large car park right next to Parliament Buildings. I wonder now if perhaps some forward looking people were saving space for this new game-changer, as it would be the perfect location for a climate commission to be the third regulatory arm ensuring New Zealand’s economic stability. Net Zero New Zealand proposes innovative thinking and land use change is required for the greater good, I believe this small piece of downtown Wellington real estate should undergo a land use change of its own.

Leave a comment