We now live in the era of the open, networked and democratised economy. Today’s information, services, platforms and products are created, distributed, and economised instantaneously through networked, social, open (and in many cases, free) networks operating on a global and local scale. Food and Agriculture, which until now, have been notably absent from the mix, are at long last joining the race. Transforming one of the most staid, socially closed and environmentally taxing industrial systems in the world.

We all are witnessing how nearly every business and industry in the world has been, or is in the process of being transformed. From healthcare (Doctor on Demand), mobility (Uber) and real estate (Zillow), to music (Spotify), banking and retail (Amazon and TradeMe), the bulk of the world’s industries are progressing forward in leaps and bounds with the democratisation of knowledge, information and open data. Linux’s free and open source software development, operating system and distribution network; Android’s open-sourced software stack for mobile devices, and Wikipedia, the world’s largest free online encyclopedia, allowing anyone in the world to access and edit articles, have also all revolutionized the way we seek, produce and share information.

Food and Agriculture however, perhaps two of the most fundamental industries essential for human and planetary health, have remained dismally unchanged for decades. Our global food system has become dangerously dependent on just a few companies to meet a high percentage of the world’s growing agricultural needs. Constrained by industrial-era economics, perverse big business monopolies and cost-crippling intellectual property laws.

The Agricultural Mafia

According to Greenpeace, four corporations – ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Dreyfus – control more than 75 percent of the global grain trade. Factory farms now account for 72, 43 and 55 percent of global poultry, egg and pork production, respectively. And five corporations – Monsanto, Bayer, Syngenta and BASF and the almost approved Dow/DuPont merger control in excess of 75 percent of the world pesticides/ agrochemical market.

The increasing consolidation of our global seed supply is equally as frightening. Seed behemoth Monsanto, which is amidst highly controversial and contested merger negotiations with chemical giant Bayer to the value of 62 billion dollars, has long dominated America’s (and much of the rest of the world’s) food chain with its genetically modified seeds and gamut of toxic pesticides. Monsanto now controls over 30% of seeds globally according to ETC Group, an estimated 93 percent of the U.S. soybean seed market and over 70 percent of US cottonseed sales, Bloomberg’s Jack Kaskey says. If the merger gets approval from regulatory bodies these figures are only set to rise.

That’s a tiny amount of profit-before-people led corporations controlling what the planet eats, and how it is produced. This near total corporate takeover of the global food supply threatens innovation, biodiversity and ultimately food security.

Environmentally, global monocultures and conventional agriculture guzzle perverse amounts of natural resources and fossil fuels. From the incredible quantities of water, chemical fertilizer and toxic pesticide use, to the fuel needed to ship crops around the world, it’s a flawed system.

The perils don’t end there. Even where perverse monopolies in the food system don’t reign supreme, almost all of the vital technological and science led agricultural advancements required for a sustainable and healthy food systems, such as sustainable seed, crop and pesticide production, are threatened by a never-ending loop of proprietary practices, restricted information and a competitive, capitalistic mindset preventing much needed progress in the industry. The last time I looked, innovative biotech companies like Indigo Ag, Caribou BioSciences, and NZ’s own Bioconsortia and Biolumic weren’t giving away their novel plant microbiome, CRISPR and UV crop enhancement technologies for free.

With so few existing players, the increasing consolidation of the agriculture supply industry and prohibitively expensive proprietary systems dominating the entire Big Food and Ag value chain, it is little wonder that incentives to promote an open, sustainable and democratized food system have been slim to none. That is, a system where any member of the community can openly participate in, and add value to food production that both reduces costs and promotes human and planetary sustainability.

Thankfully, after decades of the Big Ag and Food mafia calling the shots, some of the world’s progressive technologists, entrepreneurs and startups are starting to push back and transform a system ripe for disruption. Ag 2.0 renegades, paving the way forward towards a democratized, open and imminently more sustainable food system by bringing the networked economy, digital ag and distributed farming methods to the world of food and agriculture. In my humble opinion, not a moment too soon.

Food Computers – Opening up the Future of Farming

The launch of the Open Agriculture (OpenAG) Initiative, in late 2015 is one such example. OpenAg’s goal is to create the first open-source agricultural technology research lab and ecosystem of food technologies, that enables and promotes transparency, networked experimentation, education, and local production of food. Part of the MIT Media Lab CityFARM project, OpenAg’s first cab off the rank is the “Personal Food Computer” (PFC). Ranging in scale from personal to industrial, PFCs use sensor-actuated, controlled-environment and soilless agricultural technologies and systems to control and monitor climate, energy, and plant growth inside specialized growing chambers. Almost every imaginable arable crop is grown under the same roof.

Caleb Harper with school children and the Personal Food Computer

Principal Investigator and Director, Caleb Harper, believes our best hope for sustainable farming in the future lies with advances in technology – especially sensors, big data and open networks. So an important distinction about OpenAg and its Food Computers is not its highly efficient, localized indoor farming methods (although these technologies are also complementary to a sustainable and distributed food system), but its open source plant recipe software system that it uses to locally produce sustainable food of all origins and share this info with the world. With only 3 percent of the global population involved in the production of their own food, Harper says his mission is to enable every global citizen to become a farmer and equip him or her with a food computer. “I want to revolutionize agriculture — to move out of the industrial age and into a modern era of networked and computationally driven food production.”

Specific conditions inside the Food Computers are able to be set or adjusted manually, and are designed to mimic natural environments, or generate ideal synthetic ones. “Why import food from thousands of kilometers away when one can import the climate itself in which the food was grown?” says Harper.

In short, Food Computers enable growers like you and me to grow and share the recipes of the foods we love and want to eat without having to grow and ship them from faraway lands, all under the same roof, at the very heart of our urban masses.

Harper says while plants have similar or identical genetics, they can widely vary in color, size, texture, growth rate, yield, flavour, and nutrient density depending on the environmental conditions and climate (ie temperature, humidity, nutrient levels etc) in which they are grown. These specific conditions or climates, when maintained in the Food Computer, can be thought of as a climate recipe that produces unique phenotypic (environmental) results. For the layperson like myself, this means food traits like flavour, sweetness, texture, crunchiness etc.

As Harper explains speaking at TED, “When you say, ‘I like the strawberries from Mexico.’ You really like the strawberries from the climate that produced the expression that you like. So if you’re coding climate—this much CO2, this much O2 creates a recipe—you’re coding the expression of that plant, the nutrition of that plant, the size of that plant, the shape, the color, the texture.”

Echoing similar sentiments, David Rosenberg, CEO of the world’s largest indoor vertical farm, AeroFarms, also regularly makes reference to the fact that plants don’t need light, they need spectra. They also don’t need water or soil, they needs nutrients.

Harper’s OpenAg programme is already being met with huge success. Personal Food Computers (PFCs) have been introduced in many schools across the Boston area to encourage children to investigate and experiment with the new food production technology. Now the OpenAg team (comprising engineers, scientists architects, urban planners, and economists) is working on developing a mid sized Food Server and an even larger warehouse scale Food Data centre to cater to small-scale producers like cafeterias or restaurants and industrial-scale urban food production.

What makes OpenAg’s food computers so distinctive and appealing in terms of how they might become a real threat to the conventional Ag mafia, is that they are deliberately “hackable” and 100% collaborative. There’s no hidden agenda. When entered into an open online platform, climate recipes can be shared, borrowed, scaled up, and improved upon around the world, in real time. For free. No strings attached. Users worldwide can access, make changes and improvements that suit their specific food needs. Meaning that consumers from Antarctica to Iceland can grow sweet mangos or summer berries locally.

The programme has already attracted member companies like IDEO, LKK, Unilever, and Target, as well as affiliates and advisors including Howard Shapiro (Chief Agronomist of Mars Candy), Mitchell Baker (Executive Chairwoman at Mozilla) and Terry Garcia (CSO of the National Geographic Society). This powerful lineup suggests Harper’s goal may well become reality before Monsanto can say Round Up Ready.

Hampton_Creeks: Ben Roche prepares scrambled eggs using one plant protein

‘Blackbird™’ – the New Healthy Plant Protein Global Database

Controversial food technology start-up Hampton Creek is another player with big ambitions to shake up the world of Big Ag and Food as well as the (less than palatable) dietary habits of modern American culture. Better known for its egg and oil free mayonnaise and dressing substitutes and plant-based cookie and cake mixes Hampton Creek has, since 2015, been building (what they hope to be) the world’s largest plant database that houses a wealth of information on novel plant protein isolates and their functional properties relevant to food products.

Lee Chae, Hampton Creek’s VP of R&D, says the purpose of the database is to amass a large knowledge base of natural compounds that the company can use to create food products that are sustainable and healthy. He says the company has already built out a team of 60 R&D members comprised of scientists, engineers, and chefs to design and build the plant database’s technology platform. Last year they also transitioned from a bench-based, hands-on discovery approach, to an automated, robotics-based discovery system, that they refer to as ‘Blackbird™’. Chae did not divulge specific new product discoveries that Hampton Creek intends to launch to market with the aid of the plant database, however, he did say the company has made a number of discoveries using Blackbird™ and they are now working to develop additional novel plant based foods that will compete with traditional animal based proteins. “Common themes for the types of discoveries we target are those natural compounds that will allow us to address problems in the food industry. This includes plant proteins that will allow us to develop food products with cleaner labels, shorter ingredient lists, and healthier profiles.”

In contrast to OpenAg, Hampton Creek’s database is, however, not currently open-sourced. This does raise some questions around just how much the wider public and food system will benefit from the initiative. Nonetheless, it remains a fundamental belief of the company that there exists a tremendous number of under-appreciated plant species and crops in the world, and this data will allow Hampton Creek to interpret a wide array of plant information in order to inform farmers of new beneficial crops. “Our goal is to find, investigate, and understand them, and promote their use in food.” With machine learning and AI having become the hot new thing in Silicon Valley and the basis of almost every big new tech company emerging on the start-up scene, there can be little doubt that Hampton Creek is onto a good thing.

Sayonara One Crop Farms and Food Miles….

Trendy climate recipes and plant databases asides – the democratisation, digitization and decentralisation of our food system is also being spurred by the rise of smart, automated and machine learning farm operating systems enabling individuals and retailers to grow food locally onsite, in their own kitchen, backyard, glasshouse or grocery store – at the touch of a button.

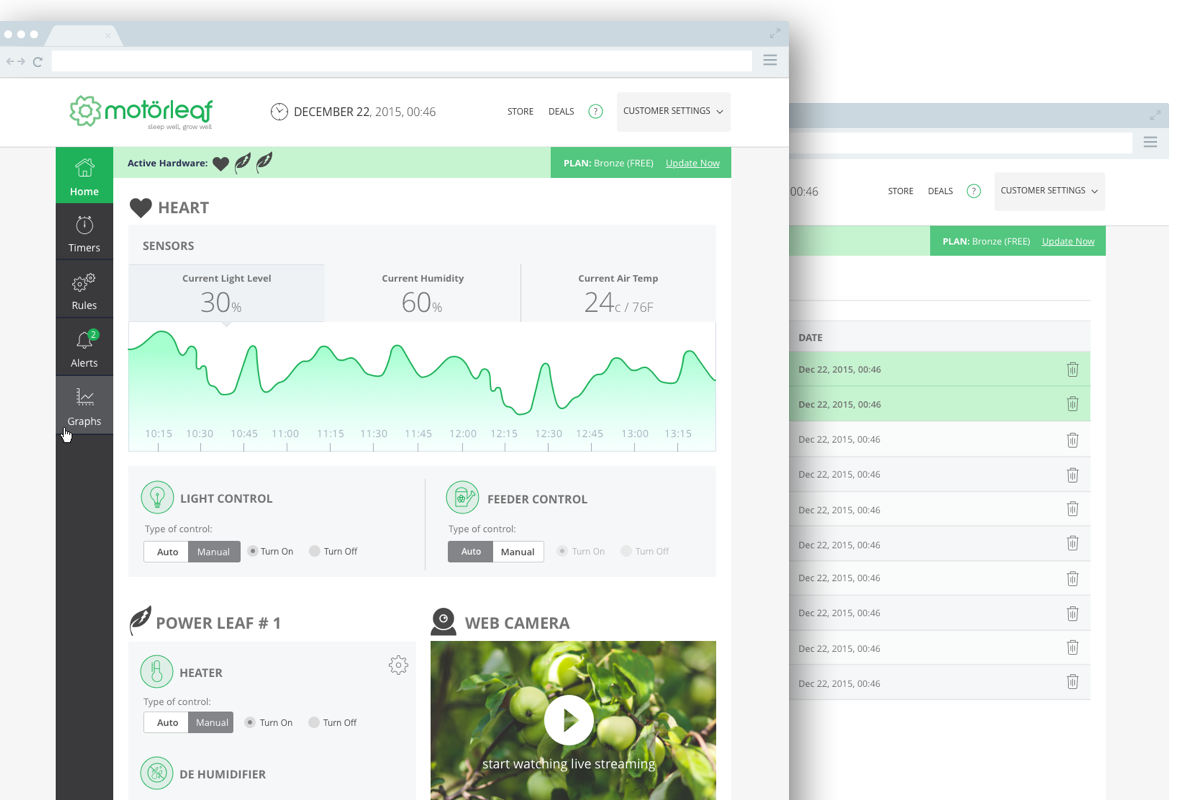

Motor Leaf Software Interface

Canadian startup Motorleaf, for example, is turning the conventional agricultural supply model on its head with its world first, fully integrated (hardware and software) wireless and plug ‘n’ play indoor growing system that turns indoor grow rooms and greenhouses into smart, connected grow operations. Launching on KickStarter in 2016, the start-up has already attracted pre-sale customers ranging from large Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) manufacturers and supermarkets, high schools and licensed cannabis farmers across North America.

Powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, Motorleaf is essentially the self- driving car of indoor growing industry. Its hardware and software systems receive over 40,000 data points per customer per week and use data and algorithms to enable a wide variety of crop types to grow themselves, advise growers on most optimal settings and predict problems and adjust crop maintenance accordingly. Its flexible and modular plug ‘n’ play system is also fully customizable to any individual’s or company’s grow space and grow mediums, and allows growers to decide which parts of their grow operation they want to control, monitor and automate. In short, it is just as suitable for green-fingered hobby growers as it is for large scale indoor crop growers or produce retailers like Whole Foods Market or Countdown.

But perhaps an even more compelling value-add of the Motorleaf system, that will no doubt help to bring us one step closer towards a distributed, democratized and more sustainable food system, is that the company plans to use its network of data and growers to connect users to each other – on an opt-in basis – to share data, plant recipes and knowledge. “Our aim is to dramatically change the world, by lowering the barrier of entry so millions of people all over the world can embrace growing crops for themselves and each other,” say cofounders Alastair Monk and Ramen Dutta.

Click and Drag Farming

Farmbot, the world’s first open-source fully autonomous precision farming machine is aiming to do similar things in the outdoor crop growing space. FarmBot’s “Bots”, essentially giant 3D garden printers, are connected to a real life version of the Farmville app that lets home growers drag and drop every kind of plant they want in their digital garden, and then transform this into real life crops. Traditionally precision agriculture and autonomous farming equipment has only been available to Big Ag in the form of massive heavy machinery and monoculture focused farming tractors costing upwards of $1 million each. FarmBot’s precision 3D printers that carry out the entire gardening process prior to harvesting, including soil preparation, seeding, plant spacing and fertilizing, change all this. They also water each plant precisely on a set schedule as well as monitoring conditions, and annihilating pesky weeds.

Like Motorleaf, FarmBot is scalable and modular to work in any situation making it suitable for a host of growing applications from small raised beds to retrofitted greenhouses, urban rooftops and commercial and industrial applications. Founder, Rory Aronson, also says it’s as easy to set up as furniture from IKEA and controllable with most devices, meaning you can play real life Farmville whilst honeymooning in the Maldives (if that’s what floats your boat!).

So far around 33 common crops (including artichokes, silver beet, spinach , potatoes, peas, pumpkin) have been loaded into Farmbot’s free and open-source software, and all operations are fully optimized using a decision support system that carries out and adjusts crop maintenance based on soil and weather conditions; sensor data, location. “Our vision is to create an open and accessible technology aiding everyone to grow food and to grow food for everyone. Our mission is to grow a community that produces free and open-source hardware plans, software, data, and documentation enabling everyone to build and operate a farming machine” says Aronson.

A clear poster child of the new democratized Ag 2.0 paradigm, Aronson wants you to steal his idea. Similar to Elon Musk’s Tesla EV technology, there are no patents pending on his revolutionary open sourced growing system and he’s happy to give away his ideas for free bringing us one more click closer towards the the democratization and decentralization of food production. “Proprietary products can allow for competitive advantage, but it’s my belief that it’s a cheater’s way out. My competitive advantage is that I’m the first to market and building a brand of trust that puts consumers first” said Aronson in an interview with AgFunderNews. “I believe open-sourced information is the way of the future. More companies are opening up about their practices and technology, in order to put the consumer first. I think people are going to respect the way we’re doing this rather than a competitor who takes everything from FarmBot and then makes it proprietary and doesn’t make it open.

DIY Opening Up the Food System

A host of smaller DIY grow-at-home indoor growing systems and apps including Grovelab, LetttusGrow, Leaf, Click and Grow are also making forays into the conventional ag space enabling consumers to grow their own fresh, delicious chemical-free herbs and vegetables in the comfort of their own home, all year round. Even Ikea has entered the indoor growing market with its hydroponic garden system. The design was born out of a collaboration with agricultural scientists in Sweden, with a target audience of those who live in apartments or don’t have a garden, as well as people who want completely fresh produce even during the cold winter months.

Just think, if data scientists can develop an open database of digital plant recipes and the accompanying distributed growing systems that enable food production of even the world’s most exotic produce within the fringes of our city limits, the relevance of traditional monoculture outdoor farms located far away from urban city mouths has the potential to rapidly diminish. No matter how behemoths like Monsanto and Bayer couch it, our current conventional and closed food system is wildly broken and a technology disruption waiting to happen.

Yes, it’s early days and many of the aforementioned start ups haven’t been around long enough to prove their success, but if consumers, supermarket chains and local crop suppliers alike see the value in such innovative growing technology and data sharing platforms, companies like Motorleaf, Farmbot and Ikea could collectively have the potential to revolutionize the current indoor and conventional monoculture crop farming industries globally. Cutting out the middleman as well as food miles and pesticides. Marrying these initiatives with innovations like OpenAg and Hampton Creek’s plant database, we might just have a chance to bring down the Ag and Food Mafia, and transform our global food system towards one that embodies resilience, sustainability and human health for the long run.

Leave a comment