The Net Zero in New Zealand report highlights ways and means of reducing GHG emissions later this century. Intensive land use, particularly pastoral farming highlights how solving this problem has become a race for technological solutions. Many of these technological solutions are fantastic, but do they address root causes?

There is no mention of the role of agro-ecological methods as if such practices are unprofessional, and yet research exists. Instead, the report promotes opportunities for agribusiness rather than solid prospects for family farm resilience. With this in mind, it’s no wonder commercial interests now consume 98% of farm revenues in developed nations like Canada leaving farmers destitute.

There are few studies that explore the role of context with GHG emissions. The emission measurements of various livestock species are conducted in laboratories. What is missing is influences of the countryside to mitigate emissions where livestock live, in the paddock. The real problem is the linear, mechanistic, reductionist perspective that struggles to embrace how the wider landscape helps manage the complexity of feeding livestock.

So while Net Zero states changing livestock diets offers opportunities it’s doubtful all the risks have been fully realised in these calculations to promote technologies in a realistic and practical sense.

Take GMO ryegrass as an example. The problem will be maintaining ryegrass as a monoculture. That will require continual herbicide sprays to prevent other plants growing in the sward so the full potential of expected benefits can be realised. However, as GMO cropping experience in North America shows, the continual use of herbicide destroys soil structure meaning more irrigation, overgrazing, and soil compaction, therefore, greater reliance on agrichemicals, pasture renovation, and other technologies.

Herbicide use is now so ingrained its ecological effects are ignored by all agencies managing land, not just farmers. Notice how roadside markers are surrounded by simplified ecological communities mostly annuals, seldom perennial species resulting in poor soil structure and erosion. All these riverside trees have been sprayed around their bases for many years resulting in erosion and chemical drift into waterways all under the guise of best practice. In each instance, council policy has focused on addressing a specific problem rather than environmental health. Simplified ecological communities reflect lower carbon sequestration than complex communities.

There is also the development of herbicide resistant weeds which then perpetuates the release of another generation of herbicide crops, and the cycle goes on. What is the carbon footprint of those unintended outcomes let alone the impact of increases in farm debt and risk which accompany them?

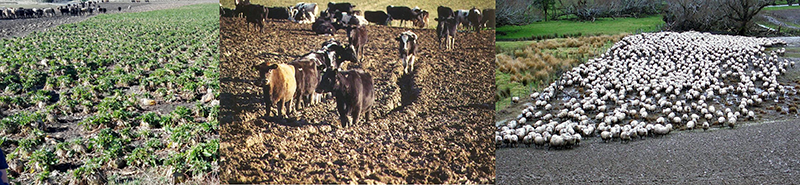

The industrial approach to GHG emissions can be seen with the suggestion of planting and grazing brassicas. The reason brassicas have been suggested is to drive down fibre intake to reduce GHG. A problem here is that fibre is essential to drive rumen fermentation to keep livestock warm during winter periods and is why livestock condition declines grazing brassicas as they metabolise their own body fat. Kale crops during wet seasons often leave livestock standing in mud which is problematic for soils and livestock. Soils can become waterlogged and anaerobic. This is because cultivation reduces soil structure and furthermore, brassicas are not useful in feeding fungal populations which are crucial for improvements in soil structure. The resulting images associated with this practice are often detrimental to livestock farming.

Growing monocultures requires intense herbicide use resulting in loss of soil cover, poor soil structure and mud no matter what class of livestock graze it in winter. Many farmers consider this undesirable but are resigned to it because of industry beliefs and advice.

Farmers have to look no further than the issues associated with fodder beet to see the problems emerging here. Primary industry promotes these methods as best practice but in reality farmers spend a lot of time supplying fibre and protein to balance a high carbohydrate fodder beet diet. What is the carbon footprint of all that labour from growing and bringing supplements to livestock instead of them just fending for themselves?

Furthermore, farmers comment that their stock becomes agitated on crops such as fodder beet. Whether it is the inability of livestock to balance their diets, or inflammatory side-effects of digestion of chemical cocktails sprayed on crops to maximise growth, stressed livestock seldom reach potential growth rates.

What is missing from the solutions offered in Net Zero New Zealand is the permaculture principle of multiplicity. These ideas benefit farmers and communities, especially when combined with no tillage, reduced agrichemical applications, and improving soil structure. Right now North American farming publications are exploding with examples of farmers employing such ideas and seeing multiple benefits to their properties and business. This phenomenon is gaining such momentum that some USDA soil scientists are openly critical of how agrichemicals and technologies commonly associated with increasing production have destroyed the foundation of farming – the soil.

Monocultures and the cultivation techniques to create them have a limited role in mitigating climate change. Instead, cropping farmers are switching to cover crops and multi-species mixes to improve soil function.

Cover crops designed for litter to cover soil surfaces improve soil structure by incorporating plants which create services that enhance soil properties and livestock performance.

They simply determine how their paddocks need to improve and then sow various plant species which create services to lift productivity or provide complimentary services.

The writers of the Net Zero New Zealand report have missed an opportunity to look more deeply into how self-organising natural systems can influence GHG emissions and unfortunately this reflects a common attitude by industry professionals. Even biodiverse grasslands create many ecological services which benefit climatic problems (Werling et al 2013) compared to cropping monocultures. Livestock managed properly sequester carbon and create diverse soil microbial communities (Teague et al 2013) and mycorrhizal fungi have a role in this too. Furthermore, what role do insect species like dung beetles contribute to reducing GHG emissions? How can that role be recognised when most global Ag and soil science models ignore their function?

There is a whole sustainable agriculture industry promoting benefits of biochar, compost, and carbon based soil conditioners but these ideas are also largely overlooked by academic and financial communities and their backers. Composting, according to the US Composting Council (2008) reduces methane and N2O emissions, particularly when carbon:nitrogen ratios are balanced, and combined with adequate aeration and moisture.

This solution is never considered, either when housing livestock and collecting their waste or in paddocks as sheet composting with pastures and crops. Effluent systems are always water based. Yet the public is aware of innovations of how a 24-hour composting system can work without machines. Popular North American farming entrepreneur Joel Salatin of Polyface Farm demonstrates this with his pigerator pork system. The Salatin family calculate how much bedding they need to soak up animal waste and then turn pigs in once the cattle are gone to aerate the bedding and allow microbes to do composting. Later the material is spread on paddocks.

A whole branch of production economics could be dedicated to working through the value of self-organising organisms and communities for farmers and environment. Instead, research seems to focus on production science as if only technology can provide solutions for corporate interests funnelling gains into intellectual properties rights and monopolising the food industry.

In fact, corporate agriculture, according to the Salatin family, often suffers from constipation of imagination when it comes to assisting farmers. For example; name a large well-known western bank anywhere on the planet that lends money based on improving ecosystem services? It’s not happening nor likely to anytime soon. A financial institution’s idea of sustainability seldom if ever extends beyond buildings that house their own headquarters.

The same goes for insurance companies. There is not a single insurance company that explores how utilising self-organising ecological systems can reduce the risk for farmers and wider communities from climate change. This thinking reflects current mechanistic management beliefs that once again drives big business. This same paradigm is responsible for what organic systems farmers know as moron disease; more land, more fertiliser, more chemicals, more irrigation.

There is much more going on to mitigate climate change at a grassroots level than is covered in the Net Zero New Zealand report. Unless there is a change in perspective many GHG reduction and sequestration solutions will simply go unnoticed and funding will be squandered on business as usual. As Dwight Eisenhower quipped “farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil and you’re 1,000 miles from the corn field”.

References:

Teague, R., Provenza, F., Kreuter, U., Steffens, T., Barnes, M. (2013). Multi-paddock grazing on rangelands: Why the perceptual dichotomy between research results and rancher experience? Journal of Environmental Management 128, 699-717

US Composting Council (2008). Greenhouse Gases and the Role of Composting: A Primer for Compost Producers.

Werling, B. P., Dickson T. L., Isaacs R. B., Gaines, H., Gratton C., Gross K. L., Liere H., Malmstrom C. M., Meehan T. D., Ruan L., Robertson B. A., Robertson G. P., Schmidt T. M., Schrotenboer A. C., Teal T. K., Wilson J. K., and Landis D. A. (2013). Perennial grasslands enhance biodiversity and multiple ecosystem services in bioenergy landscapes. PNAS 111 (4) 1652-1657

Leave a comment