Planting indigenous trees is great for many reasons. But we shouldn’t be fooled into thinking that in the fight against climate change they are better-because-they-are-natives.

Some local academics and other commentators have been recently citing an international study published in April in Nature magazine (Simon Lewis et al) which concludes that indigenous forests are many times better than exotic forests at sequestering carbon from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The article perceives forests as the most significant global driver to offset greenhouse gas emissions.

But generalising its conclusions to a New Zealand forest context is dangerous.

The Nature article (comments) studied a range of tropical and subtropical forests in 43 countries. It specifically excluded forests in countries such as New Zealand, which are temperate, or in other instances boreal (colder weather northern) forests.

While Nature assumes that a mature indigenous forest can regenerate in ‘roughly 70 years’, this certainly does not apply to New Zealand where the sequence to genuine maturity of a kauri or podocarp forest takes hundreds of years.

Moreover, the article refers to a very rapid growth rate of eucalyptus trees. In New Zealand conditions eucalyptus trees will grow at twice the rate as mentioned in Nature. Radiata pine is not far behind.

The Nature article also assumes that a harvested tree will be made into paper and similar products and the carbon released back into the atmosphere. Even assuming that this is indeed what does happen to the carbon, most New Zealand timber is used in construction. The carbon stays intact for the life of the building.

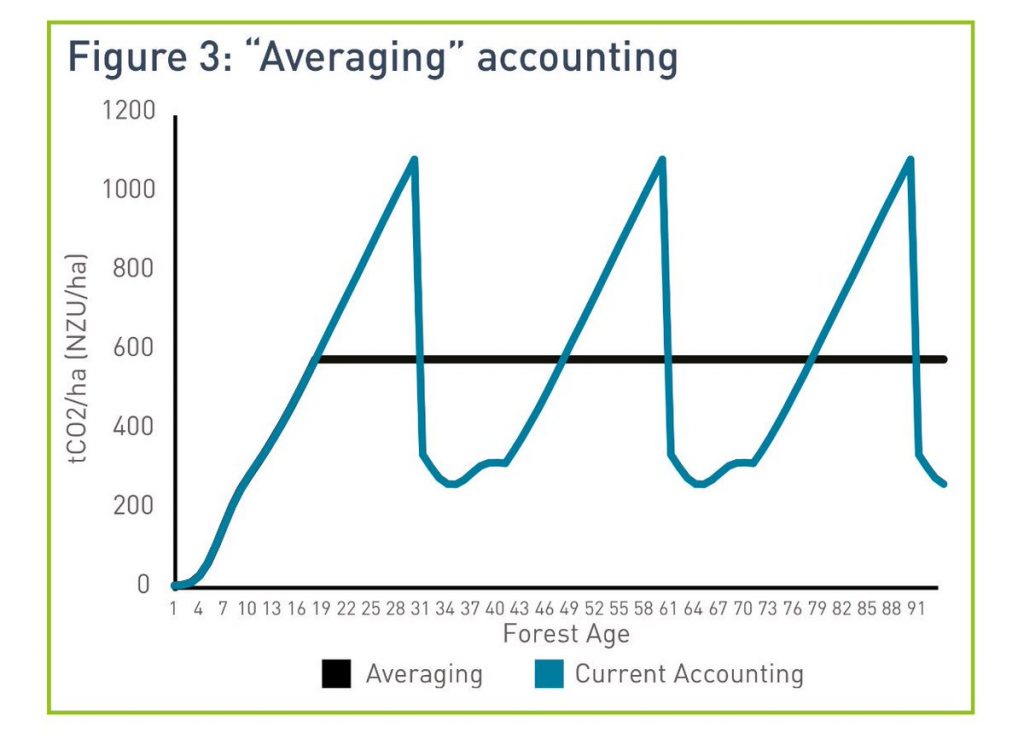

Moreover, some of the carbon sequestered remains on the site while the new trees are establishing. Over several rotations, the average carbon stored in a harvested radiata pine plantation is approximately 60 per cent of the maximum carbon stored just before harvest.

To generalise, as some New Zealand commentators have done, that a native tree will always outperform one which is introduced, is as sweeping as saying that all Ford cars go faster than all Holdens – or vice versa.

Comparisons can only legitimately be made locally by comparing the growth rate and wood composition of trees against each other in a range of environments.

We have done that in New Zealand. The results are overwhelmingly clear.

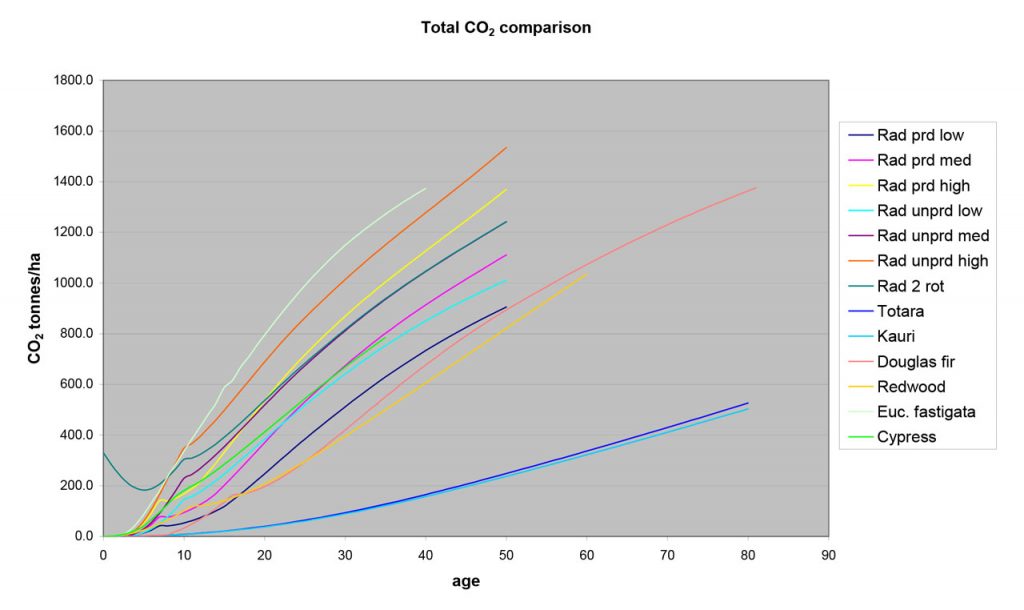

Certain studies have shown that even in the best environments the fastest-growing native trees will grow and store carbon much more slowly than our pine plantations. It will take a kauri or totara 100 years to top a 20-year-old pine.

The pines are early fast growers and New Zealand indigenous trees are not.

The pines might be harvested by rotation. After all, whatever the type of forest, the individual trees all eventually die, but the forest itself can go on forever.

Even on such a rotation harvest regime, the carbon sequestration per hectare of this average age forest is still twice that of regenerating and unharvested podocarps. Those podocarps have also taken twice as much time to get to the same level of carbon storage.

Whichever way you look at it, the pines in New Zealand are ahead in this contest. Unless you take a long-term view of at least 100 years. After all, climate change is bringing us its perils because we humans have failed to take a long-term view of our appetite for fossil fuel use over the past century and more.

But in our present situation, we need some heavy carbon lifting right now. We cannot wait for hundreds of years in the hope of a regenerated giant kauri landscape to recover from dieback disease and eventually absorb more carbon than pines could dream of doing. It would be great to see these trees come back to the North, and we would wish our descendants to walk in awe amongst them.

“But to be brutal about it,

we need early start-up engines and not late developers.

We need them now”

The consensus of the climate scientists is clear on a number of points. We have only years, and at most decades, to globally stabilise or reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. Sure, authorities disagree on the precise time scale and the sequencing of runaway collapses.

Will the temperature in some parts of the world rise so high that it is impossible to survive outdoors, before or after the West Antarctic ice sheet falls off into the Southern Ocean and drowns coastal cities? Who knows! We should not be too curious to find out the answer.

So, we do know that urgent cutting back on our gross greenhouse gas emissions is vital.

At the same time, we should utilise the most efficient carbon capture trees we can grow in order to reduce our net emissions.

Qualification is necessary. No trees, no matter how good they are at capturing carbon, and no matter how they are bred to enhance that capacity (as our plantation pines are) can keep doing the job forever. In about 100 years, if we keep relying on even fast-growing trees, there would be no suitable land left to plant.

Trees, and particularly the fast-growing exotics, are a vital part of today’s answer. In the future, we can only hope that we are able to rely on new technology and our changed behaviour to keep the climate change threat at bay.

Leave a comment