The things that are driving innovation in today’s car business are not the traditional focus of improving design, extending performance, upgrading specification and reducing cost. These are all critically important, but they don’t keep the car companies awake at night. There are three things driving the car business innovation at present – all of them relate to the technology revolution and how that is impacting on real world issues. They are:

- Climate Change

- Safety

- Urbanisation (and to some extent wealth)

In this article I’ll offer some personal thoughts on these issues and possible future directions for the global and New Zealand car business.

- Our gross and net emissions have been steadily rising over the past quarter century

- We have made an international commitment to reverse that trend and reduce our emissions by 30% of 2005 levels by 2030

- Transport (air, road, rail, shipping) constitutes 17% of our total emissions (after agriculture and energy) – and those emissions are up 60% since 1990

So what to do?

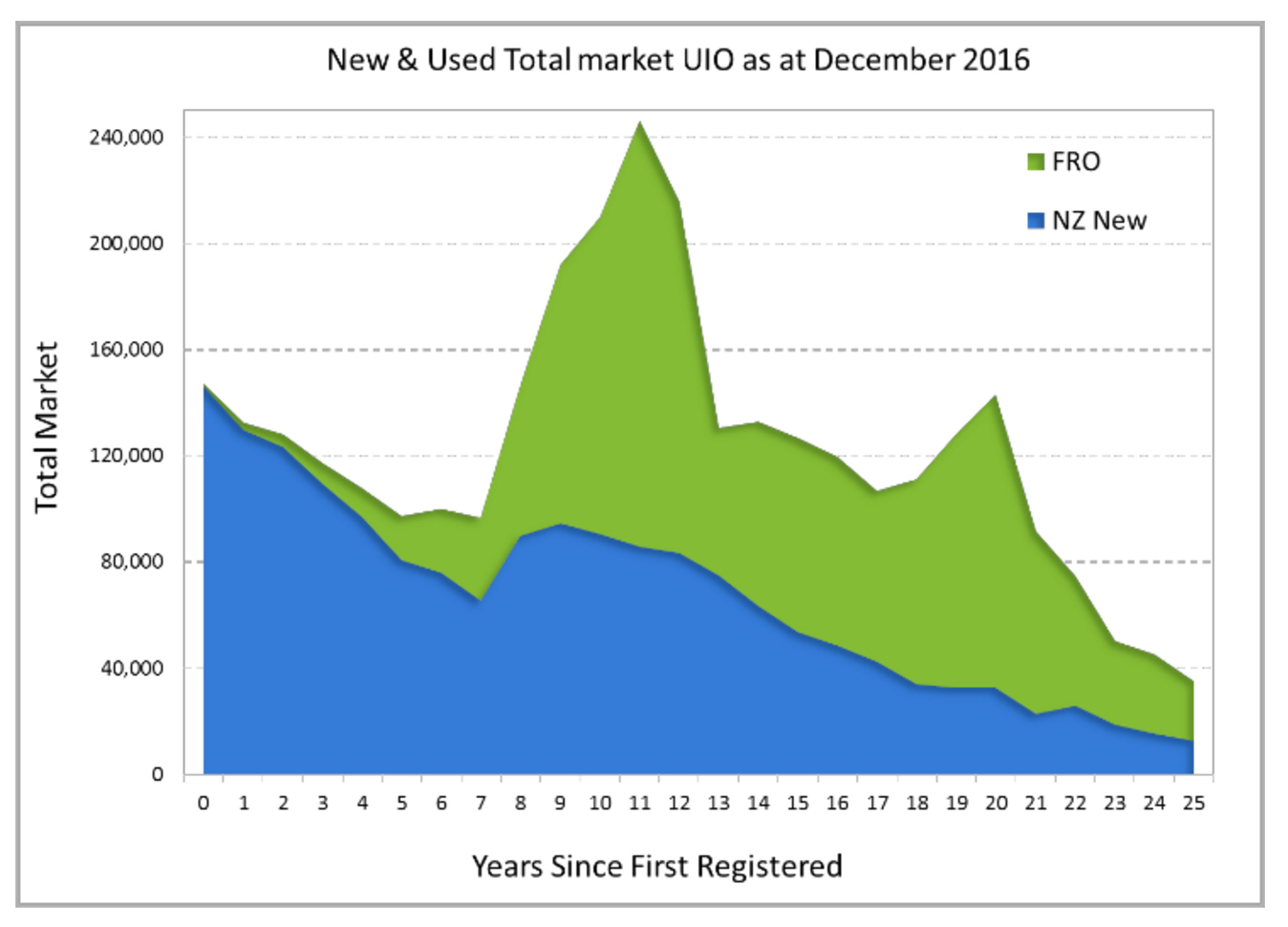

Well new cars are getting better – the average emissions of new vehicles sold in New Zealand are down 17% over the past decade to around 180 gm CO2 per km. Toyota is on track to reduce its 2005 new vehicle CO2 emissions by more than 30% by 2030, with a mixture of hybrids (HV), plug-in hybrids (PHEV), electric vehicles (EV), more fuel efficient internal combustion engines (ICE), lighter body weight etc. The problem is that new vehicles constitute just 4-5% of New Zealand’s total vehicle fleet, which itself is old by world standards. Thanks to the opening of our borders to used vehicle imports, the average age of cars on New Zealand roads has climbed from 10 to 14 years since the early 1990s, and older cars generally have a poor emissions profile compared with a modern vehicle. You can see the profile of the New Zealand fleet on the chart below, which shows the number of vehicles in each age bracket – the blue section represents cars sold in New Zealand as new (which is the profile most developed countries enjoy), while the green represents those imported used to New Zealand (the peaks at around 10 years and 20 years are due to volume surges caused by periodic FX fluctuations and the introduction of Government safety regulations).

Leaving aside the quirky access used imports enjoy in New Zealand (which facilitates the country having one of the highest motorisation ratios in the world), how will vehicles improve their CO2footprint (i.e. reducing fossil fuel consumption) in the future?

Partly it will be through the conventional ways that vehicles can be improved: lighter weight construction materials (plastics and carbon fibre replacing steel), smaller engines with forced air induction to reduce fuel consumption while maintaining performance (Toyota’s new CH-R SUV with a 1200cc turbocharged engine is a good example), improved aerodynamics and a variety of engine design enhancements that will keep the ICE viable for at least a few more decades.

However the most promising opportunities are changing the motive power. The first step in this was the introduction of petrol/electric hybrids, led by Toyota and Honda 2 decades ago. These typically improve the CO2 footprint on an equivalent petrol vehicle by 30-40%, although the cost of two engines means that one needs to drive around 15,000 km per year to get the cost saving – there is areas on almost all taxis are hybrids! Most importantly hybrids were a development step towards amore efficient motoring solution as it pushed the envelope of battery technology, regenerative braking, inverters and a host of other innovations that can be used in subsequent “environmental” vehicles.

As an aside the initial motivation for developing hybrids (and Toyota started on this course in the 1970s) was the oil crisis and the prospect that the world would soon reach peak oil and have to contend with diminished supplies in the 21st century. Developments such as shale oil and fracking have delayed the issue somewhat and the more pressing concern has now become emissions and climate change.

New Zealanders love affair with trucks and SUVs, together with a low gas price and negligible Government endorsement or support have kept hybrids to a relatively small part of the market – for Toyota they constitute just 5% of our annual business. Globally 15% of Toyota sales are HVs and sales flourish in markets where there is more focus on environmental impact: USA’s HV share for Toyota is 10% (double New Zealand’s!) but in Europe it is 32% and in Japan it is 43%.

However there may be more uptake for electric vehicles (EVs) where, thanks to the enthusiasm of Simon Bridges, Fraser Whineray and a host of other luminaries, there has been good public awareness. The Government has set a target of getting 64,000 on the roads by 2021, a target which seemed quite daunting when it was set, as less than 1,000 were operating in New Zealand. However since then the total has grown to 2,000 fuelled by low cost used import Nissan Leafs from Japan, some fashionable luxury cars from Europe and a well-priced Mitsubishi Outlander. Toyota’s offering to date is a plug in hybrid Prius, imported as a used car and converted to a New Zealand spec – it retails for $35-40,000.

Nevertheless despite the encouraging growth rate, 64,000 EVs is a tiny amount when one considers there are over 3.2m vehicles on New Zealand’s roads. Globally less than 1% of vehicles sold are electric, with the biggest market by far being China at over 400,000 per year. The 2025 projections range from 10 to 50% of sales being EV or PHEV; many of the car companies are promising a significant number of EVs or PHEVs in their lineups over the next decade. The expected surge has two main reasons: the rising cost of complying with emissions regulations in places like Europe, China and California together with the falling cost of batteries.

EVs make a lot of sense for New Zealand – because we generate over 80% of our electricity from renewable sources it is an attractive strategic option to reduce the emissions footprint of our vehicle fleet. There are still some greenhouse gas emissions from our renewable electricity production but they are minimal compared with coal or oil fired electricity generation. We apparently have enough renewable electricity available (or at least consented) to power every vehicle in New Zealand. From a climate change perspective the electric vehicle makes sense in this country. Sadly it is not quite so logical in every country – simply transferring the emissions problem from tailpipe to the (coal based) electricity generator does not help the emissions footprint. Consequently most car companies are at least partly hedging their bets on the future motive power of mobility. The alternative most under consideration is hydrogen – I’ll come back to this shortly.

In the meantime a plug in car is the fashionable option in New Zealand. That said there are some challenges remaining in the technology. There are multiple different types of battery technology and they all involve trade-offs. So far none have solved all the issues:

- Safety – avoiding a thermal runaway which causes a fire is critical (as Samsung recently discovered to their cost). That can come from things like over-charging the battery or too high a discharge rate.

- Life span is a function of how often a battery can be charged and discharged before it loses its capacity. Obviously a car company wants it to last a significant time or distance although the first owner may not be too concerned. To ensure that a battery lasts at least ten years, the car company will over-specify the battery which has consequent impacts on weight and cost. The option of swapping lightweight batteries out as a part of the ownership lifecycle remains an unproven business model.

- Performance is optimizing the battery for operating conditions (climate, hills, towing, weight, etc)

- Specific energy – the battery’s capacity for storing energy per kilogram of weight. This is still only 1% of the specific energy of gasoline. Until we get a major breakthrough this limits the range of EVs to 250-300 km between charges.

- Power – the amount of power that batteries can deliver per kilogram of weight. This is not so much of a problem – EVs tend to have explosive acceleration, despite not emitting the soul-stirring noise of a V8.

- Cost is falling fast. Back in 2009, prices were around $1000 per kwh for an automotive lithium ion pack. Today they are about $300, which is not far above the cost of consumer batteries. It used to be that an EV was considered a second car for richer, environmentally minded drivers who were prepared to pay the premium and accept the compromises of slow charging times and limited range. But as the specific energy (range) issue is solved and the cost falls, the 2020s should see EVs at a comparable price to the conventional motor vehicle with far fewer of the compromises.

We are on the cusp of solving some of these issues, but at the moment the pure EV still has too many compromises for extensive New Zealand use.

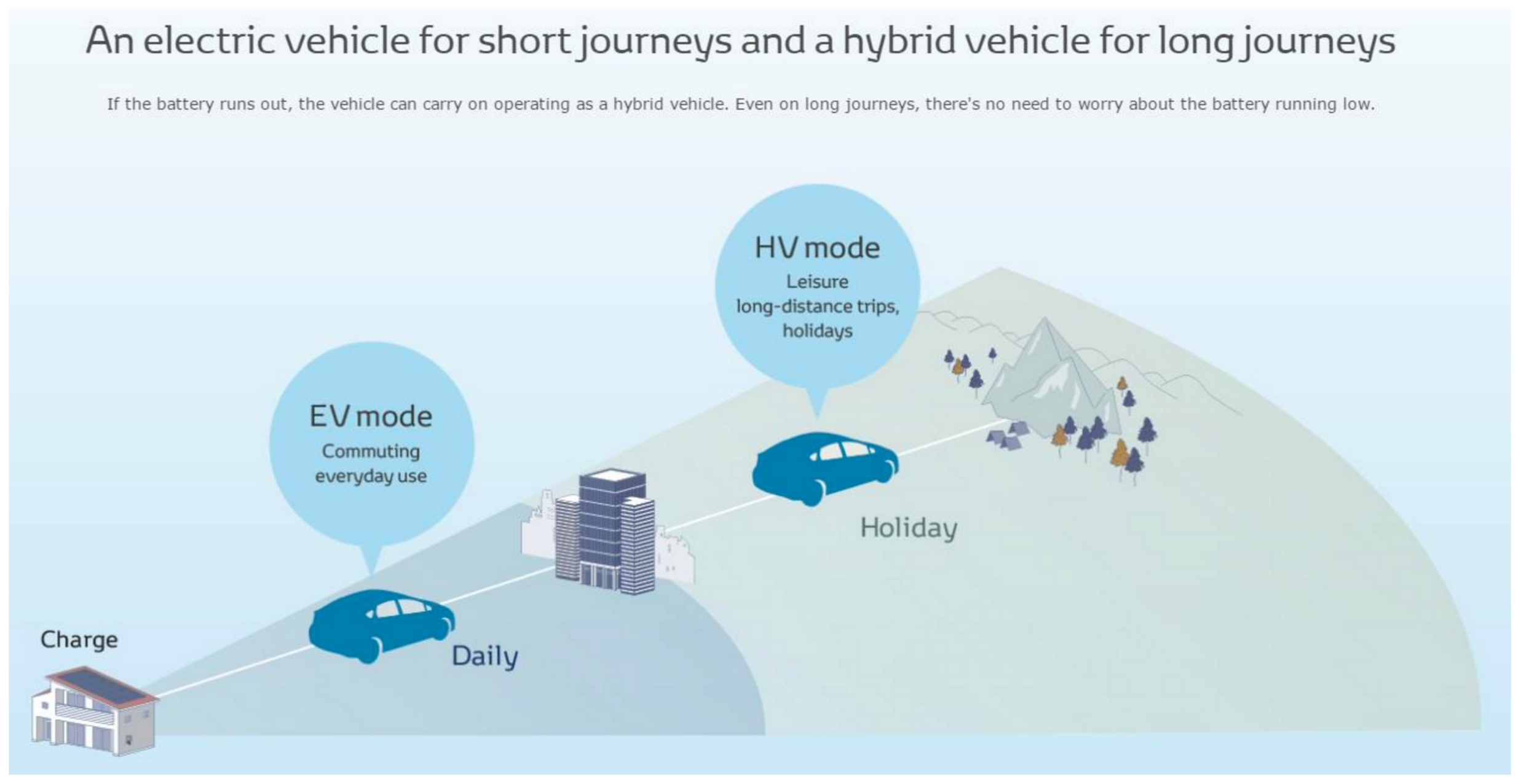

Probably the best short term option in New Zealand is the plug in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV), which charges like an EV and operates as an EV for the first 30-75 km (when ICE is at its worst – a cold engine consumes 40% more fuel and produces emissions at a similarly poor rate); it then overcomes the specific energy (range) issue by converting to a conventional hybrid when the initial charge is depleted. Thus for majority of short journeys it functions as an EV only, but when needing a greater range the vehicle can jump into petrol/electric hybrid mode.

And most New Zealand journeys are short – on average Kiwis drive 30 km per day, often in 2-3 trips(e.g. to and from work). So for a PHEV, it is likely a tank of gas will last several months.

Hydrogen

The ultimate zero emissions fuel may be Hydrogen in a Fuel Cell Vehicle (FCV). Its only emission is water but of course the real test is how you make the hydrogen – it is a little pointless using a coal fired electricity supply to make hydrogen! Although many of the issues developing an FCV are now resolved (a fine example is the Toyota Mirai on sale in Japan and parts of USA and Europe), there are significant issues of scale (to lower costs) and challenges of establishing a distribution infrastructure; accordingly it is unlikely we will see hydrogen being a significant fuel in New Zealand for at least a decade or so.

Potentially large trucks and buses with specific routes may be able to take advantage of hydrogen as the infrastructure can be built around key route nodes (rather than trying to blanket the whole country in hydrogen refueling points), but in fact the biggest opportunity for New Zealand connection to hydrogen may be in export. If we can harness our renewable electricity supply to hydrogen manufacture, a good outcome may be the export of transport fuel to places like Japan and China who will be the early adopters of the FCV.

Longer term it seems the choice of mobility power train will be a function of cost, distance traveled and size of vehicle – it is all about physics. For shorter trips in smaller vehicles, battery power is likely to be the best strategy. For longer trips with more weight (in other words buses and trucks), it would seem that hydrogen powered vehicles have significant merit. But for everything in between and for the compromise situations that most New Zealand driving requires, the hybrid solution seems the best – both conventional hybrids and the plug in variety. There is no silver bullet and looking out a decade or more, New Zealand will see a proliferation of technologies rather than adherence to the traditional ICE.Finally on the topic of climate change – a challenge. Globally Toyota has set itself 6 big sustainability commitments to be achieved by 2050 Pertaining to this piece, the most significant is the plan to reduce the average emissions on our vehicles by 90% by 2050. The base year is 2005. That means a big commitment to EVs, PHEVs, FCVs and even conventional Hybrids. Toyota in New Zealand is part of those commitments, but we have supplemented it with internal goals of reducing our carbon footprint in New Zealand by 30% by 2030, in line with our national Paris commitment – and that is not just in the products we sell, but in our total footprint of energy, air travel, freight, etc. It is a daunting target but one that we would challenge all New Zealand businesses to adopt and surpass.

A primer on Safety

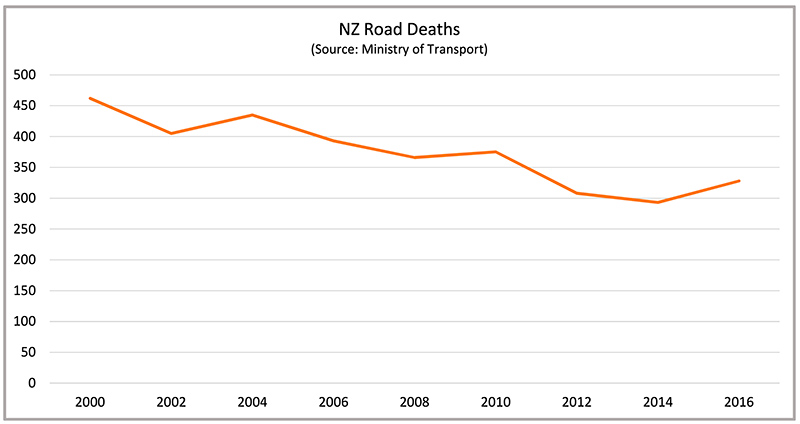

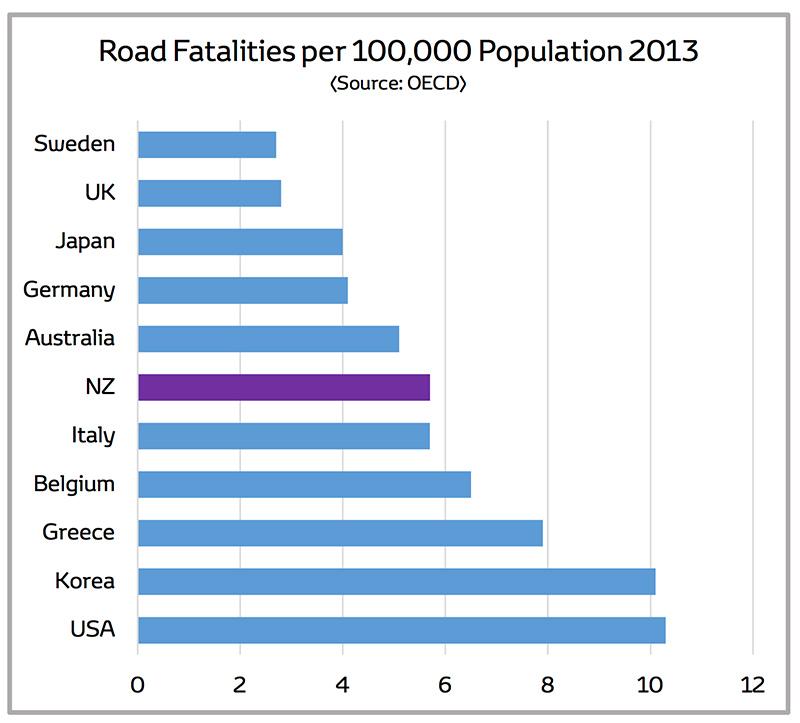

The road toll around the world is horrific – motor vehicle accidents kill 3,500 people per day, a higher death rate than most of this century’s wars. Even in New Zealand the mortality rate is daunting. Although our road toll is generally coming down (despite the rapidly growing population), and we are 40% better than the US, we are still no better than Italy and far worse than places like Germany, Japan, Ireland and the UK. We are double the death rate in Sweden.

Leaving aside the human cost of road accidents, the economics are also daunting. The Government estimates the annual cost at $3.4 billion (including insurance, medical, repair, lost time, etc.) – that’s $800 per person every year. There are plenty of imperatives to maintaining our improving trend inroad safety.

There are lots of reasons why the road toll is getting better: road design, driver education, legislation and law enforcement all play a part. I will just discuss the evolving design of the motor vehicle.Basically this falls into two parts – active and passive safety.

Passive safety incorporates all the ingredients that help save your life when you have an accident – most notably crumple zones (so the car absorbs the impact of the crash rather than the person), seat belts, air bags, etc. There have been massive advances in this area over the past couple of decades – have a look at Nigel Latta’s video for old (big) car vs new (small) car crash testing which shows some startling comparisons that may encourage you to update your vehicle.

Active safety helps you avoid an accident altogether and, thanks to the technological revolution, there is massive progress happening in this area.

- At the basic level almost all new vehicles now have vehicle stability control, which significantly lowers the risk of a vehicle accident. Many cars have hazard identification features such as blind spot monitors, lane departure warnings and pre-crash warning systems. Another feature gaining popularity are automatic headlights that dip when following another vehicle or in the face of approaching cars.

- At an intermediate level some luxury cars are starting to have autonomous braking systems to stop a crash if the driver does not heed the warnings. The 2017 Lexus LS will also include autonomous steering to avoid a pedestrian, along with a heads-up display warning of pedestrians ahead and providing cross traffic alerts.

- Of course the ultimate use of technology is to have a fully autonomous vehicle (AV) that drives itself hopefully avoiding the main reasons for car accidents: inattention, speeding, impairment. At its heart the autonomous car is a collection of technologies that largely already exist: Google Maps, Route Guidance Software, Radar, Cruise Control, Lane Keep Assist, etc. The autonomous vehicle aims to integrate these technologies and allow the vehicle to progressively reduce the required human inputs.

As these levels of active safety technology have become increasingly available at a falling price, all car companies are working hard in this space. Fundamentally we don’t want our customers dying in our products. There seem to be two broad approaches:

- The Chauffeur strategy, where the car will do everything. This has been well publicised by vehicles like the Google ‘bubble’ car which does not even have a steering wheel.

- The Guardian Angel strategy, where the driver is still expected to control the vehicle, but the

car can take over in emergency situations or particular conditions.

My expectation is that the Guardian Angel incremental approach is likely to be the way most development takes place – that way technologies can be trialled and evolve in real life situations. The Chauffeur approach is the more appealing from a PR perspective but has significant ethical and practical issues to get right before a product release will satisfy both sceptical customers and cautious regulators.

Whatever approach is adopted, the autonomous vehicle offers a wide range of benefits. Safety is obviously the primary one as an AV can mitigate human frailties – an AV won’t get drunk, text while driving, speed or get over-tired. They will also help to keep our aging population mobile as they can compensate for failing eyesight and reaction times. AVs will also allow platooning where cars or trucks can join up close to one another (almost like a train) and thus save fuel and reduce congestion.

The autonomous vehicle also gives significant impetus to the concept of car sharing, because if you can summon an autonomous vehicle at any moment and be dropped at any location without the need to find a park, there may be a large number of customers who decide they don’t need to own a car. Their time spent commuting can be spent more productively (whether that is answering emails, surfing the web or eating breakfast). Building design will evolve with less need for personal garages and parking space. Because we can share autonomous vehicles we can have less on the roads (so saving both congestion and infrastructure costs) and the cost of motoring will fall as we effectively pay for usage rather than the full capital cost.

Of course there remain many hurdles to overcome. Some are technical such as getting all the technologies to work together with sufficient accuracy and redundancy that they will provide a safe and reliable journey. Some are ethical/legal: how does a computer make the choice between running over a pedestrian to save the lives of the occupants and avoiding the pedestrian but hitting a truck which kills the occupants? And how will issues of liability be settled? Plus there is the challenge of cost – these new AVs are fiendishly expensive to develop but like many consumer IT products, they quickly become “must-have” products at ever-lower prices. As soon as they become available company directors, faced with the burden of health and safety obligations will quickly have to evaluate when they make them mandatory for their staff. Managing the transition to autonomous vehicles over the next 10-20 years will be a significant challenge for business, customers and regulators alike, but the prize of road safety is too big to ignore.

Urbanisation

As we all know urbanisation is increasing, not just in Auckland but globally. This has inevitable impacts on transport, especially where there is a lack of public transport infrastructure tuned to the level of population (again a significant problem in Auckland).

At a global scale the related issue is the growing level of wealth; one of mankind’s great achievements of the past few decades has been to lift billions of people out of abject poverty – increasingly the world’s masses are able to buy refrigerators, TVs and motor vehicles.

The OECD estimated that in 2009 the global middle class was 1.8 billion people with 664 million inEurope, 525 million in Asia and 338 million people in North America By 2020 that total is expected to hit 3.2 billion and by 2030 it will be up to 4.9 billion. The bulk of the growth will come from Asia (including China and India). The Asian middle class will be 66% of the global total by 2030, up from just 28% in 2009.

The big challenge is that most of these people are going to live in cities and they are going to have expectations of motor vehicle ownership. At present vehicle ownership ratios are quite disparate. In the US (and New Zealand) there are over 700 vehicles per thousand people. But in most of Asia (where the new middle class is emerging) the rate is under 300 per thousand. So the aspiration is for doubling or trebling of vehicle access. So car consumption is going to go through the roof as wealth grows and everyone wants a car.

Now congestion is already terrible in places like Bangkok, Beijing, Shanghai, Manila and Jakarta – so how will they cope with increasing urbanization and wealth and even more motor vehicles? Obviously increasing vehicle numbers puts pressure on the world’s resources although the discovery of shale oil has put off the day of running out of gas a bit longer. But as we already discussed in a previous paper the issue is now emissions, rather than oil supplies.

Much of the focus on solving issues of increased vehicle demand and congestion are IntelligentTransport Systems (or ITS). These are a grab bag of technologies and business models to try and solve our traffic (and safety) issues. They can help cut traffic congestion, parking issues and pollution.

There are multiple technologies I could pick up on, including:

- The clever new highway recently rolled out in Wellington where variable speed zones are designed to assist traffic flows.

- The ITS interfaces with autonomous vehicles (as mentioned in a previous paper on safety),where smart vehicles and smart traffic systems could interface to improve flow and reduce fuel consumption.

A key technology that has had extensive (good and bad) publicity is vehicle sharing. To be clear there are basically three different types of sharing:

- Ride hailing is where you effectively call a de-regulated “taxi” via an app on your phone. The one most common in New Zealand (and many Western countries) is Uber where the car can be used as both a taxi when working and a private vehicle when off duty. There is an even bigger operation called Didi Chuxing operating in China which reportedly is doing over 1 billion rides per year (more than twice the size of Uber)

- Ride sharing where you can join somebody in their car to drive on a trip they are already making – effectively you make a financial contribution to a journey the car owner was already going to take. It is car-pooling with strangers via and app. Uber is starting to play in this space with UberPOOL now operating in some US cities, but the one that appeals to me is Bla Bla Cars. This is a European car-pooling business that you can specify how much talking you will do by the number of Blas you select.

-

Car sharing is where a car sits idle until the traveller goes to pick it up and uses the vehicle, before returning it to its original or another location. This is not dissimilar to a car rental but by having the car operated (unlocked and started) and billed by a phone app, there is significantly less overhead involved. In its present form the process needs designated locations for the vehicles but ultimately the ideal solution is the autonomous car which can come to you where you need it and once your journey has finished, can leave you and parkitself. The most well-known of the car sharing businesses is Zip Car.

Needless to say many of the car companies (including Toyota) have investments, joint ventures or trials operating in all of these categories, as over time the sharing economy seems destined to disrupt the present car ownership model. When one considers that a private vehicle is only used 5-10% of the time and even fleet vehicles are often idle for majority of their life, the present model is ripe for disruption as technology enables new forms of ownership. Consider for example the DHB with its fleet of cars for district nurses and distributed healthcare; most of these are idle at weekends and at night – imagine the cost reduction if they could be rented out with a simple phone app. I know there are lots of legal issues and complexities but as technology makes these options available, behaviour will follow the economics.

As car sharing changes the dynamics of car ownership, it will both lower the cost of mobility (through greater utilisation) and reduce the congestion on the road (mainly by increasing passenger numbers per vehicle). There will be the added benefit that as cars usage gets cheaper and vehicles are more utilised, New Zealand’s vehicle fleet will tend to become younger – which has benefits for both emissions efficiency and road safety.

This eventually leads us towards the concept of Mobility being sold as a Service (MaaS). Instead of buying a car and paying for fuel, servicing, licensing and the like, one can envisage a future where you receive a monthly bill for mobility – car rental, running costs (potentially mainly electricity usage) and road user charges. The Government may not wish to tackle the political hot potato yet, but a RUC that takes into account location and hours of use would have great power in encouraging efficiency improvements and reduced congestion.

Not everyone can or will want to give up their car. Trades people who have their tools of trade in the back of a ute or van will not be able to move to a car sharing concept Nor will those car owners for whom the vehicle is part of their identity and self-image be happy about travelling in a nondescript vehicle, shared with strangers. But I suspect faced with the improving cost efficiency of car sharing and public pressure to reduce congestion in urban areas, we will reach a tipping point that radically shifts the ownership paradigm.

This leads me to my last point on the congestion issue – the most comprehensive solution is not a silver bullet, rather an integrated approach to transport, something that is easy to write and fiendishly difficult and expensive to implement. A combination of mass transit and heavy freight needs to be complemented with small “last mile” solutions for both people and freight. This integrated structure will probably involve all of the mobility technologies I have been discussing in these three articles: fuel cell trucks and buses, plug in hybrids, electric vehicles (including small 1- person EVs), autonomous vehicles, car sharing along with all the other ingredients of ITS needed to make personal mobility sustainable in the 21st century.

Finally in conclusion a little bit of history. The father of car sharing was not Uber. It was in fact theJitney Bus. In 1914, a car salesperson from Los Angeles called L P Draper invented the Jitney Bus. He saw people queuing to get onto trolley buses and decided that it would be quicker to offer them a car journey where customers would share rides in a small vehicle. He offered a cross town trip for 5cents, or, in slang terms of the day, “a jitney.” Within a year his team were doing 150,000 rides a day in Los Angeles (about the same as Uber is doing today in LA, 100 years later). In 1915 there were60,000 Jitneys across USA.

Needless to say the trolley operators fought back and lobbied for tough regulations that effectively destroyed the Jitney business. The outcome was the regulated taxi business…AND mass ownership of the private motor vehicle. People soon figured that if you couldn’t share cars, you had to own one and the 20th century became a boom time for the car business…and all its consequential challenges that I have been describing in these three articles.

Today, technology has put us on the cusp of some revolutionary changes in the car business. With the potential advent of mass electrification, fuel cells, autonomous cars and a variety of car sharing models that will eventually result in mobility being sold as a service, there is the potential to deal with some of the great challenges the motor vehicle has brought to the 21st century: climate change, road safety and the congestion that accompanies urbanisation.

Alistair Davis

Leave a comment