It’s two years now since the launch of Our Forest Future, where I called for 1.3 million hectares of new forest planting for a greener, more climate-aligned economy. A lot has changed since then, which I’ll come to soon, but first I want to talk about a lesson I’ve learned.

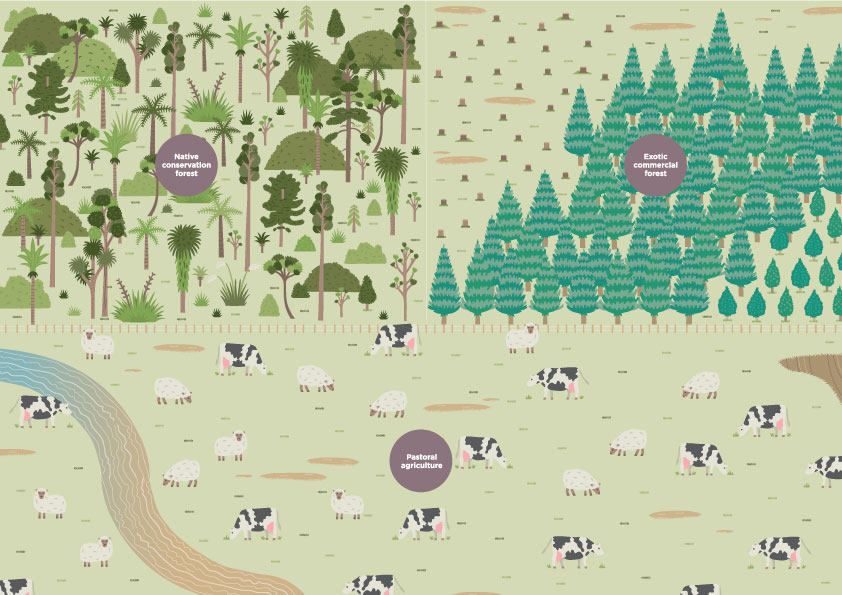

In Aotearoa New Zealand, many of us see forests as a binary choice. It’s either native conservation forests, managed under the principle of look-but-don’t-touch, or it’s exotic plantation forests, typically Pinus radiata managed under a clear-fell system. Not everyone sees forests this way, yet this siloed thinking pervades public conversations.

Indeed, I hadn’t realised this until I published Our Forest Future in 2016. Some accused me of advocating for 1.3 million hectares of intensive exotic forestry, not an appealing idea to many people. Still others accused me of advocating for native forests only, which they regarded as a whimsical, even irresponsible, suggestion, because slow-growing natives are expensive to plant and poorly aligned to short-term net emissions targets. In short, I was two different enemies to two different groups of people.

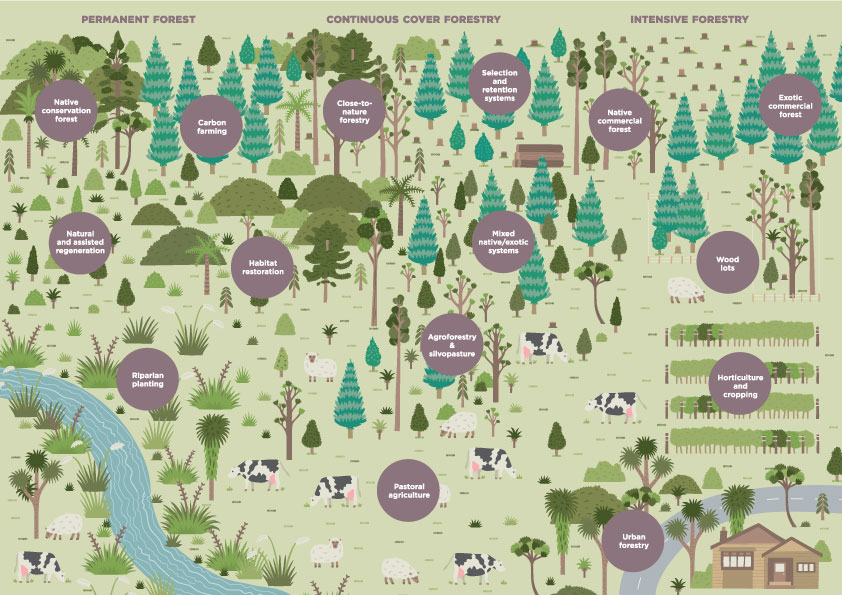

Actually, what I called for was appropriate diversification. It was a refresh of that old forestry adage: “Right tree, right site.” My view then, as now, is that the forests we need are the forests that create the greatest public value: social, environmental and financial. And this is bound to change from site to site, depending on landowner preferences, financial constraints, soil type, slope, microclimate, access to seedlings, and so on.

A more diverse future forest is the obvious way forward. Yet it is also obvious that we don’t do enough to explore innovations and opportunities, to see what mixes of species and management systems might strike a better balance of social, environmental and financial outcomes. Instead, our regulatory, financial and research frameworks remain largely beholden to a siloed way of thinking, where the landscape is treated as either native conservation forest, exotic plantation forest, or pastoral agriculture – with little in-between. This siloed vision of the landscape looks something like this.

Today, courtesy of The Policy Observatory at AUT, I’m publishing a new discussion paper, The Interwoven World | Te Ao i Whiria. Something of a sequel to Our Forest Future, it lays out an alternative vision of our landscape which deliberately interweaves and intermingles a variety of land uses in order to create a more prosperous landscape. The image below ought to make clear that the Interwoven World isn’t about either/or, but all and more.

Of course, some landowners are already doing this. They are already experimenting with wood lots, carbon sinks, mixed native/exotic systems, riparian margins, silvopasture, and more. Yet many more landowners would probably like to experiment in this way – but can’t. They can’t find the capital, time, capacity, or technical advice. Or they can’t make these land uses financially viable, even when this diversification would create the most value for rural communities, or avoid environmental harms.

These barriers shine a light on who this discussion paper is really written for. Not so much the folks on the ground, making tough decisions about what to do with their land. Much more the folks who make decisions about the wider regulatory framework, about policy design and enforcement, about research funding and agendas, about investment and supply of finance, about who to insure and on what terms.

We can’t ask landowners to make land use changes that would risk, or induce, insolvency. So, if we want a more interwoven, well-integrated landscape, we need to precipitate a systems change that makes reforms in all these areas (and more), that better aligns what is financially sustainable with what is socially and environmentally sustainable.

Today there is a unique opportunity to instill that change. Of course, one of the new Government’s flagship initiatives is the One Billion Trees Programme, funded through the Provincial Growth Fund. But what is more important than meeting this target is creating the conditions by which this target may be sustainably met. Here lies the path to genuine transformation of the landscape, not just the superficial alterations that we might precipitate by throwing grants at the problem.

And we are seeing the foundations of this systems change. The Zero Carbon Bill, currently under public consultation, could create the stable, meaningful carbon price that would make permanent forest a financially viable land-use choice. The $15 million boost to the Sustainable Farming Fund could accelerate research into the diverse forest systems that might break us out of our path-dependency on clear-felled Pinus radiata. New National Environmental Standards for Plantation Forestry, as well as proposed reforms for the Resource Management Act, aim to lift minimum standards. Finally, the resuscitation of the New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, augmented by Statistics New Zealand’s work on environmental accounting of natural capital stocks and flows, can help us to reimagine how we evaluate national success.

Change isn’t only being driven by Government either. Trees That Count, which mobilises grassroots conservation groups around the country, has counted the planting of over 14 million native trees now, recently boosted by the Provincial Growth Fund. Meanwhile, throughout New Zealand, we are seeing the acceleration of a rebranding and reorientation of financial flows, variously known as “climate finance”, “sustainable finance” or “green finance” (see the recent Climate Finance Landscape report for the Ministry for the Environment that I co-authored). The most prominent examples – such as Auckland Council’s certified climate bond for low-carbon transport infrastructure – are not in forestry. But it is only a matter of time until investors start demanding products, such as continuous cover forestry, that deliver the right mix of social, environmental and financial returns.

I’ve been working on one such project, the Native Forest Bond, with support from Foundation North’s GIFT fund, to mobilise private capital for establishing continuous native forest on highly erosion-prone land in pasture (a concept paper is available here). But this is just one example of how innovative investment vehicles could function as “enablers” in the low-emissions transition, in particular the creation of a climate-aligned landscape. How can we facilitate what the Productivity Commission is calling an “inclusive transition”, a shift to a low-emissions economy that doesn’t leave people behind?

The key is to change our systems, but first we need to change our minds. My new discussion paper is available here.

Leave a comment