What is Impact Investment?

The Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN) defines impact investment as follows:

Impact investments are investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Impact investments can be made in both emerging and developed markets, and target a range of returns from below market to market rate, depending on investors’ strategic goals.

Globally, this GIIN definition is the one most commonly accepted, and the one we will use for the purpose of this project.

Within this definition, the basic practice of impact investment involves three core characteristics, or principles:

Intentionality – an investor’s intention to have a positive social or environmental impact through investments.

Expectation of return – the investment is expected to generate a financial return on capital or, at minimum, a return of capital.

Impact measurement – a commitment by the investee to measure and report on the social and environmental performance and progress of underlying investments, ensuring transparency and accountability.

For further clarification, these characteristics mean that:

- An investment is not an impact investment unless it is originally motivated by a goal to contribute to social and environmental solutions – when social and environmental outcomes are unintended co-benefits of an investment they are not considered within scope.

- An impact investment is not a grant or donation by a new name. Neither is it the purchase of an activity, product, or service that results in a social and / or environmental outcome (i.e. government funding a public service). There needs to be a transaction that delivers a material financial return alongside the delivery of impact.

- The performance of an impact investment is evaluated using a wider accounting basis than economic return alone. Impact (investment) measurement seeks to capture a holistic record of value creation, potentially over a quadruple bottom line but usually tailored to specific areas of intended impact. In the language of economics, externalities, both positive and negative, are incorporated into performance metrics.

- The impact created should be additional to what would have happened anyway, and without the investment being made.

Beyond alignment with these core principles impact investments are not limited to specific issues, returns, or asset classes (a group of investments with similar characteristics).

The financial returns targeted by an impact investment depend entirely on the motivations of the investor, and can range from below market (concessionary or ‘impact first’) to a risk-adjusted market rate (‘finance first ). Equally, the instrument and asset class of an impact investment depends entirely on the investment proposition, and can span fixed income, private debt, private equity, public equity and debt, and also novel hybrids, such as quasi-equity.

As long as there is intent, the potential of a financial return, and appropriate measurement – an impact investment can be made anywhere, by anyone, into any proposition, through any structure, for any amount. It is simply a tool to finance blended social, environmental, economic value creation and generate aligned returns – as the Impact Management Project put it:

“Everything we do affects people and the planet. Managing impact means figuring out which effects matter – and then trying to prevent the negative and increase the positive”

Understanding Impact:

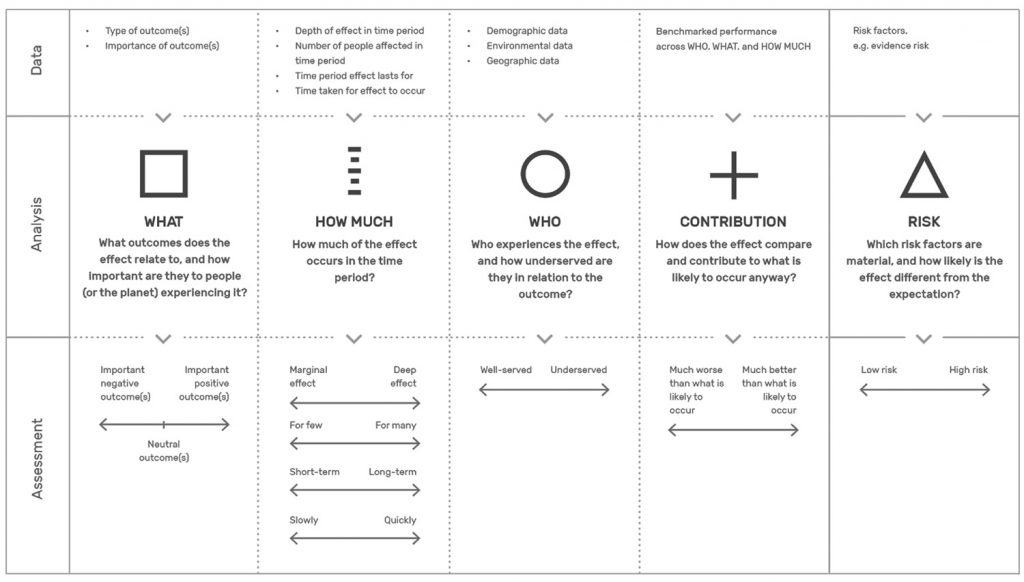

One of the best resources for getting to grips with ‘impact’ is the ‘Impact Management Project’, a collaborative effort of more than 700 organisations to establish shared fundamentals for how we talk about, measure and manage impact. Alongside strategic frameworks and toolkits, they articulate some key questions that an impact investor should ask to bring rigour to their decision making.

- What outcome, positive or negative, will the activity drive? Is it important to people or the planet. An outcome may be determined to be important based on our own opinion, guidance by professional experts, or through shared consensus like the Sustainable Development Goals.

- How much impact occurs? Consider:

- How much does the activity contribute to an outcome (Depth)

- How many people are impacted (Scale)

- How long does the impact last (Duration)

- Who experiences the impact, and are they underserved in relation to the outcome(s)?

- What contribution will the activity make in relation to what is likely to occur anyway? Consider whether the activity:

- Leads to more or less important positive or negative outcomes, and/or

- Is more or less significant (in terms of depth or the number of people it occurs for or how long it lasts for or how long it takes to occur), and/or

- Occurs for people (or planet) who are more or less underserved than those currently experiencing it.

- What are the risks that the impact is different from our expectation, i.e. unintended consequences?

- What is ‘good’ information (completeness, accuracy, relevance) to understand our impact?

- When do we collect information to understand our impact?

- Who bears the cost of collecting information about impact?

- How do we share information with others?

- How do we share information about a portfolio of many diverse enterprises?

Figure 1: Mapping the Impact of an Investment

https://impactmanagementproject.com

How does impact investment relate to other

forms of ‘responsible’ investment’?

Impact investment is often confused with other concepts such as ‘Responsible Investment’, ‘Ethical Investment’, or ‘Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Investment’. Equally, impact investment can also be conflated with concepts such as ‘Social Finance’, ‘Community Finance’, and ‘Venture Philanthropy’.

As we look to build the market in Aotearoa New Zealand, we need to be clear what we’re talking about and be talking about the same thing. This section unpacks these various distinctions.

The spectrum of responsible investment

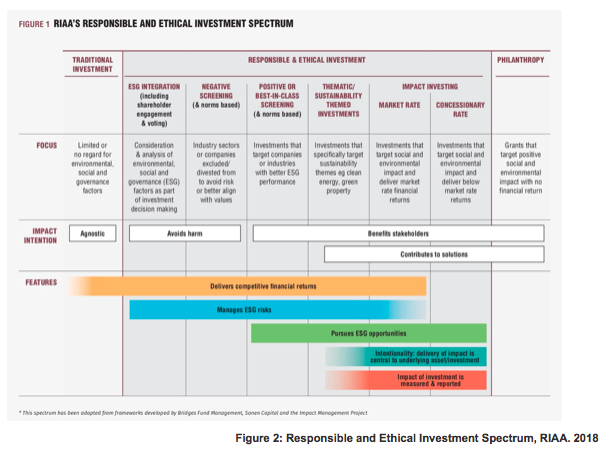

The RIAA depicts ‘Responsible and Ethical Investment’ along a spectrum, bookended by ‘Traditional Investment’ at one end, where investments are agnostic to social or environmental impacts, and ‘Philanthropy’ at the other, where grants (‘gifts with objectives’) are made to fund social or environmental impacts without any expectation of a financial return.

Within this spectrum, investments are made with increasingly robust levels of scrutiny, from a basic ESG position where investments are screened to rule out negative social and environmental impacts (‘negative screening’), all the way to impact investment where social and environmental impacts are intentionally pursued and measured as an integral part of the investment’s overall performance.

It’s important to note that moving along the spectrum does not necessarily mean diluting financial returns. Rather, the movement from left to right should primarily be understood as increasing intentionality, specificity, and rigour of measurement in relation to impact. Put simply, ESG investing represents investments that avoid harm, ‘Socially Responsible Investing (SRI)’ represent investments that create general benefits for stakeholders, often indirectly and unquantified, and impact investing is the provision of finance to tackle specific social and environmental issues with verification and accountability. It should be stated that this inevitably introduces new costs, considerations, and requisite capabilities, in respect to due diligence and management.

Of course these practices are not mutually exclusive, with impact investment portfolios often being nested within a wider responsible investment strategy. In a report summarising insights gained from a series of engagements held in early 2018 between David Carrington, an expert in the field of impact investment, and New Zealand-based investors, Giving Architects state the following:

“The opportunity to develop a variety of suitable investment options using debt, fixed interest and equity to deliver Impact Investments from Responsible Investment portfolios is significant. Aiming to utilise three to five per cent of Responsible Investment portfolios for Impact Investment for the right products is a reasonable expectation, based on discussions at several meetings and forums.”

However, at this early stage of market development, including the absence of established secondary markets, if impact is a portion of a portfolio, investors may also need to be comfortable with restricted liquidity for that portion.

Risk and return… and impact

Because impact investing is driven by social and environmental objectives, the practice evolves the calculation of risk-reward to one of risk-reward-impact. This means investment opportunities with higher risk profiles and / or below-market financial returns may be acceptable, for some investors, when the potential return on impact is attractive enough – particularly where impact is being created in areas of market failure and / or underserved populations.

These potential concessions, in themselves, are not defining characteristics of impact investing; they are part of the toolbox with which to tackle difficult issues. Impact investments are not soft investments – they simply consider a broader range of value, and adjust the risk-return ratio accordingly.

Different impact investors will be prepared to be flexible on financial returns depending on their individual objectives, constraints, and the opportunities available to them. Often individual investors will have a varied mix of impact investments within a portfolio, tackling different issues, with varying risk and return profiles.

Of course, this flexibility will not always be desirable, or possible, for many fund managers, company directors, or trustees who have specific fiduciary duties in relation to the investments, and investment strategies they oversee. While these duties are not always as clear cut as having to maximise financial returns, there are material obligations that often need to be legally reviewed on a case by case basis when impact investments are being made from funds with conventional settings. This can create both real and perceived barriers to ‘doing’ impact investment, especially in a nascent market where precedents, and the confidence, to do things differently are often limited.

However, it shouldn’t always be assumed that sub-market returns are at odds with legal responsibilities. In 2017, Foundation North commissioned two reports from the Centre for Social Impact and Ᾱkina: ‘Introduction to impact Investment’ and ‘Engaging in Impact investment’. The second report discusses this specific point of fiduciary duty in relation to impact investment and the responsibilities of Trustees:

“Prudent’ investment and the ‘fiduciary duty’ do not always require the maximisation of return according to its risk profile for each individual investment. For example, an investment made for the purposes of furthering a foundation’s charitable purposes or strategic programmes that provides a sub-market rate of return may still be prudent if there is careful consideration of the investment and how to offset this shortfall.”

Impact investing vs. incremental impact

While the GIIN definition that we have explored holds strong in the majority of discussions around impact investment, there is a growing debate about whether to broaden the concept to include all investments that have some sort of positive impact. In other words, turning the ‘responsible investment’ spectrum into the ‘impact investment’ spectrum. Agitating for this expansion (or dilution depending on your point of view), the UN-backed Principles of Responsible Investments (PRI) have framed the original definition of impact investment as the ‘traditional’ definition. They refer to the overall spectrum of ESG and SRI as ‘mainstream’ impact investing, where any business activity delivering products or services that have some benefit to society or the environment are in scope. This blurring of this distinction raises some key tensions, not least between the potentially competing priorities of scale and integrity.

On the upside, by including all investments that provide positive incremental impacts in the bucket of ‘impact investment’, even where unmeasured and unverified, you quickly reach a level of scale that is material relative to the vast global flows of capital. Scale is convincing and compelling, and, indeed, every positive impact matters.

However, it also creates the risk of diluting practices, standards, and ambitions before they have had the chance to gain traction. This issue of ‘impact integrity’, like green-washing before, has become a major concern for some of the pioneers of impact investing. Many of whom set out to foster economic transformation and systemic responses to the most pressing social and environmental issues, and not to provide cover, or license, for the continuation of the status quo. Indeed, it does raise interesting questions, neither simple to answer or dismiss, when you have institutions that were complicit in the Global Financial Crisis, and who continue to finance extractive activities and tyrannical regimes, also now managing some of the largest ‘impact’ funds.

The takeaway point for this report, is that trade-offs are inevitable companions of scale, and that strong governance is the best means to navigate the market growth we both need and desire. The establishment of these controls, through cooperation, institutions, and regulation, will deliver the best outcomes when driven through proactive strategy, not least because they will be difficult to retrofit.

Coming at ‘impact investing’ the other way around

It is also important to note that this spectrum, and much of the language evolving around ‘impact investing’, is set in the context of the mainstream investment industry, and the narrative of modern global finance. However, the underpinning practice, if not the language, of ‘impact investing’ also has deep roots in the social and community sector, and also in the philosophies and practices of traditional cultures.

Co-operative and community finance have long been based on the principles of reciprocity and solidarity, prioritising societal wellbeing and collective benefits over individual profits. These specific Pākehā-framed principles are analogous with Māori tikanga, and many other indigenous cultures around the world, where community, nature, and future (and past) generations are understood as stakeholders of economic development and priorities in everyday practices. Today, a large, if less visible, movement of ‘social’ and ‘community’ finance initiatives can be understood to overlap the practice of impact investing, if not always identifying with the terminology.

Add to this the emergence of ‘venture philanthropy’, the practice of making targeted, strategic, and proactive grants, along with other supports, and we end up with a confusing bundle of terms, ideas, and identities that are starting to find convergence. Between progressive parts of the private sector, grass-roots mutualism, the values of indigenous peoples, and the evolution of charitable giving, we are seeing an emerging alignment, if not a consensus, between key pillars of society. An alignment on how finance, and more broadly the economy, can be reshaped to serve a sustainable development agenda.

The size of impact investment activity

The GIIN estimates that in 2018 the global market size of impact investment (assets under management (AUM)), was around US$228bn. Based on data drawn from their ‘Annual Impact Investor Survey’, they report growing activity across six continents, with AUM increasing by 13% per year over the last five years. Amit Bhatia, CEO of the Global Steering Group for Impact Investment (GSG), predicts that the market will constitute at least US$300bn by 2020.

Within the US$228bn, they estimate two thirds of investors seek normal risk-adjusted, market rate returns, a sixth are prepared to take returns below, but close, to market rate, and a sixth are primarily impact-led, with significant flexibility around financial returns. The average deal size across the respondents was US$3m.

In respect to investment performance, 98% of the GIIN survey (2018) respondents report that their investments were meeting, or exceeding, expectations on impact, and 91% on financial returns.

Using the looser definition of ‘impact investing’, or investments making an impact, the UN-backed Principles of Responsible Investment initiative estimated the global market to be US$1.3tn in 2016. Still small compared to the approximate US$100tn of global investments, but registering and growing.

Closer to home, the biggest dataset on market activity is offered by the RIAA, who survey their 230 plus members on an annual basis. In 2018 they reported an impact investment market in Aotearoa New Zealand of NZ$100m, with no recorded change from the previous year. From the same survey, the SRI market was estimated to be NZ$86.4bn, and negatively screened ESG investments constituted NZ$97bn. The whole Responsible Investment market was estimated to be NZ$183.4bn, with year-on-year growth of 40% – reflecting the profound pushback from consumers to having their KiwiSavers deployed in destructive industries.

The survey data on the size of the Australian impact investment market provides an interesting comparison, reporting AUS$5.8bn AUM in 2018. This total is up from $1.2bn in 2015, and includes the somewhat distorting issue of AUS$4.9bn worth of ‘Green Bonds’.

RIAA are forthcoming that this data doesn’t tell the whole story, and certainly not for Aotearoa New Zealand where much of the impact investment activity is undertaken without being accounted for at an aggregated level. Certainly, anecdotal data points (including from the philanthropic sector and niche intermediaries working in the impact financing space) suggest impact investment activity is increasing yearly. If nothing else, this disaggregation in data reveals the diverse nature of actors seeking to employ impact investment principles and practices, and the fragmented nature of our current marketplace.

The supply and demand sides of impact investment

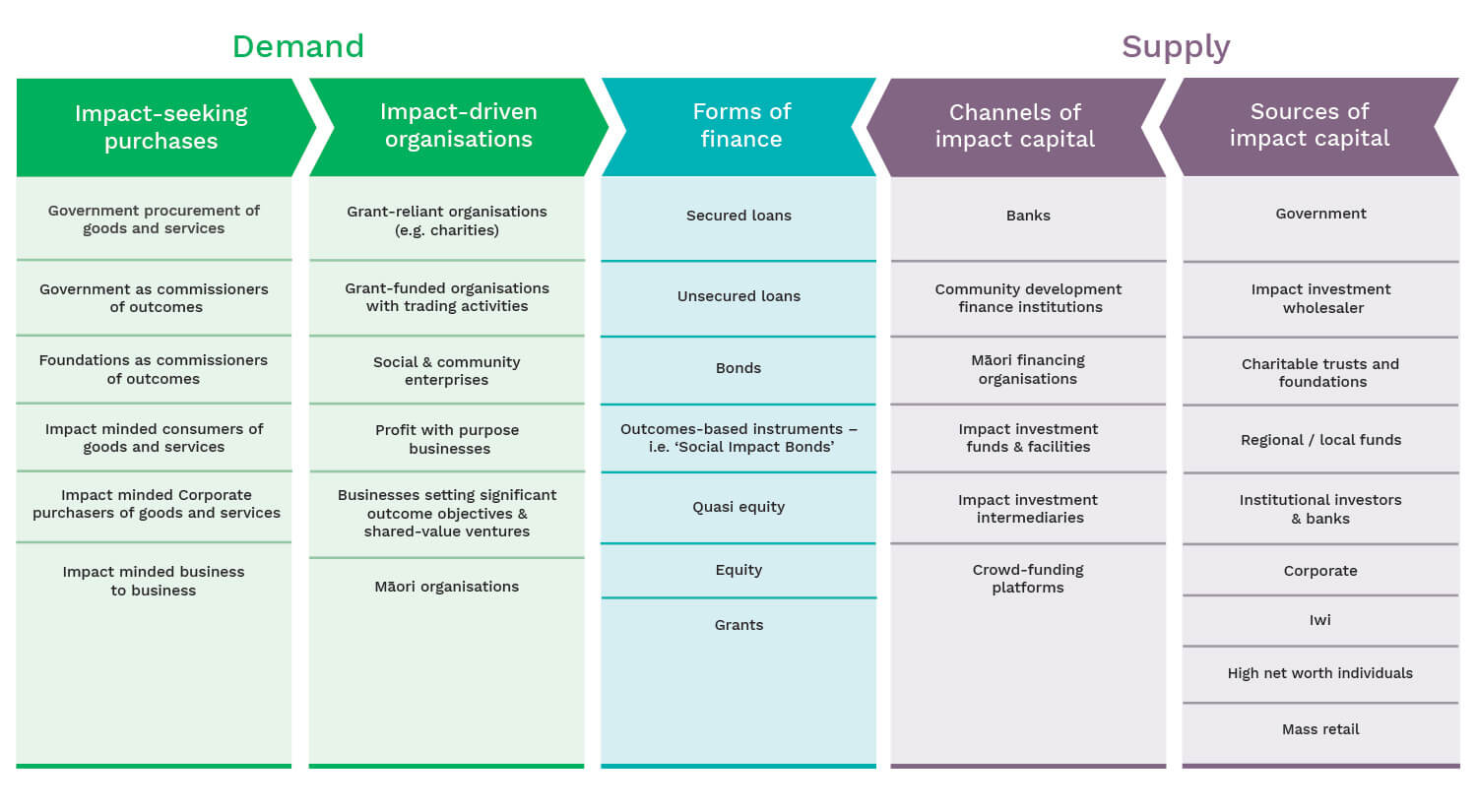

If we accept the assumption that impact investment activity will grow in Aotearoa New Zealand, we will see it increasingly span the interests of institutional investors, philanthropists, business, iwi, angel investors, charities, cooperatives, social enterprises, community organisations, public sector agencies, religious institutions, education and research institutions, and engaged citizens.

These actors can combine in multiple combinations to create investments that are structured in different ways, to achieve different purposes, through different markets opportunities, and with different end-customers. As in mainstream investment, some actors will have primary roles on the supply or demand side, and others will potentially have multiple roles across different investments. For example, a charity may be an investor, the investee, or the customer of product / service financed by an impact investment.

In addition to supply and demand-side actors, in maturing markets, specialist intermediaries have emerged to facilitate transactions, design bespoke instruments, build and prepare proposition pipelines, and, in some arrangements, take responsibility for verifying the impact performance of the investments they broker.

Who’s investing and in what? The breakdown of a national market

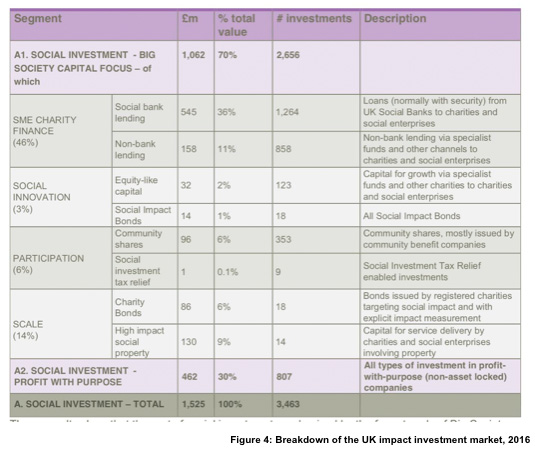

Big Society Capital (BSC) is the UK’s impact investment wholesaler and a market building organisation. To get a sense of how our impact investing market might look like in the future, it is interesting to review BSC’s data on the break down of the UK market, that they value at around £1.5bn in 2016.

Visit site:Big Society Capital

The innovation edge

In order to resource activities that are often excluded from mainstream finance, impact investment practice is driving innovation in a number of ways. This has included the provision of flexible products and credit enhancement to leverage and increase access to capital, increasing the active participation of more people in investment, and the creation of whole new markets.

Flexible investment

Many impact investment opportunities offer the potential for significant social and / or environmental outcomes but are perceived as having high financial risk and / or offering low financial returns. Other propositions may suffer from a lack of information or track record given the novelty of the approach, or the market being operated within. In these situations, accessing investment that is flexible, either in terms of risk, returns, securitisation, or repayment periods, can be the difference between interventions happening or not, and positive outcomes being delivered as a result.

As a result, flexible investment options / products are an important part of a functioning impact investment market, and both require and enable cooperation between different types of investor – some of whom are prepared to offer credit enhancements and gain leverage by taking a subordinated position.

Tailored credit enhancement approaches can encourage the flow of capital to investment opportunities by improving the risk-return profile and enabling more parties to invest. The providers of these enhancements are usually ‘impact first’ investors, public or philanthropic actors, who are primarily motivated by amplifying social and environmental outcomes, and fostering market development. The GIIN defines this approach as ‘Catalytic First-Loss Capital’ (CFLC), and it can be deployed through a variety of instruments. It could mean taking junior positions in equity or debt structures, providing guarantees, or making grants to offset returns.

Taking this kind of position may seem to be a bad investment decision from a financial viewpoint, but from an impact perspective, it makes a lot of sense. They attract commercially-focussed capital that otherwise would not be invested, and attract resources to tackle issues, often characterised by market failure, at a scale that could not otherwise be achieved.

Third Sector Loan Fund

Many charities and social enterprises without significant reserves struggle to access investments to aid their growth unless they have security (i.e. a tangible asset). The Third Sector Investment Fund was set up (in 2014) to address this barrier by providing unsecured loans of between £250k and £3m to charities and social enterprises in the UK. Loans are focussed on supporting organisations that work with marginalised, excluded or vulnerable individuals and groups. The fund structure was able to offer these terms by employing CFLC at two levels. First, a subordinated investment of £1.5m made by the Social Investment Business Foundation, then a second-loss position of £15 made by Big Society Capital, the UK’s impact investment wholesaler. This model then enabled banks and other mainstream institutions to invest and finance charities and social enterprises. Santander committed £13.5 million, believed at the time to be the biggest single investment by a mainstream UK financial institution into a third party impact fund.

Increasing participation

The supply of investment has traditionally been sourced from institutions with significant funds, specialised intermediaries, or directly from a small number of individuals who have the skills, appetite, and resources to undertake due diligence and negotiations for themselves. In the last few years, these arrangements have been disrupted by the arrival of crowdfunding, where individuals and organisations seeking investment can engage their communities, customers, and peers, and transact with them directly. Vertical channels to access capital are now complemented by horizontal platforms, where large numbers of people can now invest small amounts of capital efficiently in an unrestricted range of propositions, using a variety of structures.

While not exclusively employed for impact investment purposes, crowdfunding has become a major conduit of it, particularly in respect to facilitating risk capital and small-size capital raises, which are often cost prohibitive through other channels. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where early-stage finance for social enterprise remains limited and adhoc, notable social ventures such as Conscious Consumers, Ooooby, Eat My Lunch, Ethique (see case study), and Hikurangi Enterprises, have all successfully raised capital via PledgeMe, the primary crowdfunding platform that focuses on social impact. It’s worth noting that PledgeMe has used crowdfunding to successfully raise capital for its own growth, over two progressive rounds.

While there are risks associated with more ‘open’ investment, these are somewhat offset by the (individual) stakes being smaller, and also the ‘risk insulation’ that comes from having more customers, or direct stakeholders, having ‘skin in the game’ – a direct interest in the success of the investee. Indeed, ventures who have undertaken crowdfunding campaigns to raise capital have also experienced an accompanying increase in sales.

On this point, crowdfunding is not just a convenient way for (impact-focused) organisations to access finance, it also represents a highly aligned approach where form matches function, and where there is a natural fit between the values and motivations of investors and investee. One area which is likely to see significant growth in this respect, is the number of community-owned assets (i.e. a leisure centre run by the community for the community) and platform cooperatives (think Uber if it was equally owned by the drivers themselves). Put simply, assets that exist with a collective purpose and have lots of stakeholders, will natural align with collectively sourced finance. Crowdfunding is currently the most cost efficient way to facilitate this.

Community Shares in the UK:

In 2016, around £96m of impact investment was transacted through ‘Community Shares’ in 353 individual deals. This constitutes 6% of the UK total market, and more than six times the amount invested through ‘Social Impact Bonds’.

New market mechanisms

Beyond financing positive impacts as co-benefits in established markets, i.e. transitions to renewables in the energy sector, impact investment also plays a facilitating role in the creation of new markets where verified social / environmental outcomes themselves, become the purchased / exchanged commodity. A familiar example of this is the carbon market, where the mitigation of emissions is pegged to an economic value and then transacted. Other examples include Social Impact Bonds – where positive outcomes around homelessness, recidivism, and education have all be rewarded with financial payments.

These types of transactions represent the practical (contractual) implementation of concepts known as ‘payments for results’, ‘pay for success’, or ‘outcomes purchasing’. In these arrangements, impact investment plays the role of providing upfront capital, enabling activities to be delivered, with the investors taking on the risk that outcomes will be delivered (and rewarded).

These mechanisms are not without controversy. Critics have pointed to the over complication of financing activities that should simply be funded, price gouging by consultants, the efficacy of measuring intangibles, and the ideological appropriation of nature and / or human experiences, that should never be priced or traded.

Alternatively, proponents argue that the pricing of outcomes (externalities) doesn’t degrade their inherent nature but does ensure they are valued within an otherwise myopic economic system. Issues that we know to have inherent value but are too often not valued, can be brought into the systems we use to manage resources – the ‘tragedy of the commons’ can be avoided. They would also point to the scarcity of public funds to tackle persistent and escalating issues, and the benefits of having the means to direct resources to reward actual outcomes, rather than to rote fund activities.

All of these arguments have validity. These novel mechanisms can be powerful in many situations but won’t be appropriate in all. They can bring scale, efficiency, and innovation but they may also create unnecessary complications and lead to cherry picking of outcomes that are more easily attained, and the neglect of those that are harder to reach.

Innovative market mechanisms that can bring new resources into play will be important in the development of impact investment in Aotearoa New Zealand, and also in geographies such as the Pacific Islands. They can be highly challenging to design and implement but can be game-changing when done well. Rather than being inherently right or wrong, what is important is that these tools are employed for the right reasons, in the appropriate circumstances, by people with the right skills, motivations, and values.

The Murray-Darling Basin Balanced Water Fund:

The Murray-Darling Basin Balanced Water Fund was established by The Nature Conservancy Australia to provide water security for Australian farming families while protecting culturally significant wetlands that support threatened species. The AUS $27m Fund invests in permanent water rights in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin and allocate these rights in a smart way to achieve blended value. When water is scarce and agricultural demand is higher, more water will be made available to agriculture. When water is abundant and agricultural demand is lower, more water will be allocated to wetlands.

Key points

- Impact investment is built on three core principles: the intention to create a positive social or environmental impact, the expectation of a financial return, and measurement of the impact that is achieved.

- The financial returns targeted by an impact investment depend entirely on the motivations of the investor and the relative potential for impact. They can range from below market returns (‘impact first’) to a risk-adjusted market rate (‘finance first).

- Impact can be understood to be on a spectrum with ESG and SRI investing, where ESG represents investments that avoid harm, and SRI represents investments that create general benefits for stakeholders that are often unquantified. Impact investing seeks to tackle specific issues and will have high levels of verification and accountability.

- In 2018, the global market size of impact investment was estimated to be around US$228bn. In Aotearoa New Zealand the market was estimated to be NZ$100m but due to a lack of aggregated market data, this figure doesn’t include the true extent of activity.

- Impact investment is driving multiple innovations, including: the creation of new markets, increases in investment participation (supply and demand), and the blending of different type of finance (and investors) to create flexible financing options and products.

Why Impact Investment?

As we have discussed, this is a time of unprecedented change, connectivity, disruption, and opportunity. While the prospects of humankind, by many measures have never been better, we also face persistent and growing challenges, that are combining to create dangerous levels of risk in our social, economic, and ecological systems. This trend is detrimental to our communities, planet, and businesses, and undermines our prospects for long-term safety, well-being, and success. Helen Clark, in her former role as Administrator of the UNDP, succinctly captured the pivotal nature of our time:

“Ours is the last generation which can head off the worst effects of climate change and the first generation with the wealth and knowledge to eradicate poverty. For this, fearless leadership from us all is needed.”

To address this challenge, in 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by 193 countries, as an ambitious and holistic roadmap to guide collective advancement and well-being. Also in 2015, the Paris Climate Conference (COP21) achieved global agreement on combating climate change. For all intents and purposes, these two bold and ambitious agreements have set the strategic framework for global economic development up until 2030, even if their viability is threatened by increasingly fraught political environments and a colossal price tag.

Certainly, there is an explicit acknowledgement that if these goals are to be achieved, governments will need to work with both business and civil society, and that the muscle of the global capital markets will need to be brought into play. There are indications that this is starting to happen. Data from EY’s 2017 Global Investor Survey revealed that institutional investors are increasingly focussed on social and environmental risks and returns, and Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock Capital, sent a message to the markets in his recent letter to CEOs:

“Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, we are also set to see changes in corporate governance, with legal experts suggesting that action on climate change is both a fiduciary and health and safety responsibility. At a macro-level, the Government’s Living Standards Framework is setting new, and potentially profound, metrics for national success, that incorporate a holistic view of capital: natural, social, human, and financial. This pioneering approach will be properly implemented for the first time in 2019, when the first ‘Wellbeing Budget’ is set.

The financing gap

It is now three years since commitments to the SDGs and the Paris Agreement were made, and there is little evidence that the additional investment of US$2.5tn per year, required for their implementation, is forthcoming as quickly as it is needed. As of yet, we are not seeing the actions needed to reshape the capital markets and redirect investment towards our sustainable development. There remains a financing gap between what we have and what we need.

Closer to home, the New Zealand Government estimates a cost of between NZ$14-36bn to meet our commitments to the Paris Agreement, for the period 2021-2030. Add to this the other challenges we face in respect to housing, child poverty, health, aging, and education with already stretched resources, and we are left with three basic options to meet our commitments: raise taxes, raise national debt, or facilitate more private and community sector investment into social and environmental issues, enlisting business-based approaches to play a more significant role.

This is a key ‘why’ for impact investment – we have existential drivers, development goals, and a financing gap that needs bridging. But if this case for action is not enough, there are other opportunities and drivers to support the case for proactive market development.

Unlocking latent capacity

When looking to grow impact investment, much of the attention focuses on increasing the participation of the private sector and institutional investors. This will be important, but significant capacity also sits in with the non-profit sector (NPS), primarily made up of organisations structured as charitable trusts and incorporated societies, including religious institutions and most philanthropic actors.

The opportunity to increase NPS engagement with impact investment is underpinned by a natural alignment around mission. Non-profit organisations’ (NPOs) exist to deliver charitable and community-based outcomes, so the opportunity to deploy their capital towards social and environmental impact investments, as well as their day-to-day activities, should be an intuitive step to make. The Tindall Foundation is a notable example of how a philanthropic organisation can deploy its whole balance sheet towards impact, as highlighted by the case study with the Housing Foundation.

However, at this time the majority of NPOs separate the management of their assets from the management of their operations, or in the case of philanthropy, their grant making. Generally, an NPO’s investments are geared to maximise financial returns, to ensure the future security and / or generate profits, in order to make grants. While this is a rational approach, as more impact investment opportunities come to market we can expect to see more NPOs making the strategic and structural shift towards impact investment in their portfolios.

The New Zealand Cause Report, produced by JBWere, estimates that the total asset base of the NPS amounts to NZ$58bn, with net assets amounting to NZ$46bn. Out of this around NZ$20bn is deployed in investments and endowments. This sum represents a significant block of capital in the economy, that is mission-aligned and could be set to work on delivering social and environmental outcomes.

NPOs can also play a critical role in building the pipeline of impact investment opportunities by using grant funds to build the capacity of organisations seeking investment, and providing (proxy) seed capital. They can also contribute to overall market development through funding initiatives that improve information and intermediation.

Better business, better for business?

There are also drivers on the demand-side of capital that would be benefited by a more structured and deliberate approach to market development. Much of this relates to the rise of social enterprises, the rebirth of tribal economies, and the ramping up of progressive practice in the mainstream business sector.

Social enterprise

Over the last decade, there has been a significant growth in the practice of ‘social enterprise’ – best understood as an overarching term for a variety of organisations that use commercial methods and business models to achieve social and / or environmental outcomes. Social enterprise is not new – co-operatives, indigenous businesses, and trading arms of charities have pursued social and economic objectives through business activity for hundreds of years. What is new, however, is the convergence of these diverse approaches under an overarching movement, and the rapid emergence of a new generation of impact-minded entrepreneurs and businesses. These factors have combined to foster a mass expansion in social enterprise activity across the world.

As a reference point, there are estimated to be around 100,000 social enterprises in the UK, while 1.3 million business (representing a collective turnover of £165bn) define themselves as ‘mission-led’. Reports from Australia, UK, and Korea, all indicate that social enterprise activity, in their respective jurisdictions, has doubled within the last decade.

Instrumental in this growth has been the formalisation of sector development strategies that seek to increase the scale and effectiveness of social enterprise activity. This has naturally led to increased demand for appropriate, aligned, and accessible capital, and created an intersection with the development of impact investment markets.

While there is no reliable data on the size and scope of social enterprise in Aotearoa New Zealand at this time, the New Zealand Government recently commissioned a sector development programme, delivered by the Ākina Foundation. This programme will develop data baselines along with other activities to grow capability, and improve access to both finance and markets. Outside of this top-down approach, social enterprise networks and other support activities are emerging, organically, across the country.

The tribal economies

Adjacent to the growth of social enterprise, and central to the economic future of Aotearoa New Zealand, are the resurgent ‘tribal economics’, where Māori and Pasifika businesses are being built with increasing confidence, underpinned by strong collective values and principles of stewardship. As Iwi take their place as key engines of the economy, their influence on the orientation of capital markets, and their role in the development of the domestic impact investment market, will be pivotal.

Progressive business

Outside of explicitly purpose-led business, in all its various forms, evidence now suggests that being a better business (by society and the environment), also makes for better business in itself. Recent research from Axioma (2018) and the Boston Consulting Group (2017) both indicate that companies with better environmental, social, and governance standards are typically recording stronger financial performance than benchmarks. Analysis from the RIAA corroborates these findings, especially over the longer-term. While there may be many reasons for this correlation, it is fair to assume that capital will increasingly look to flow into more socially and environmentally conscious businesses if they continue to offer good returns.

Over the last decade we are seeing increasingly bold and progressive strategies from New Zealand corporates and businesses, both through individual and collective actions. This includes the 2018 launch of the ‘Climate Leaders Coalition’, where 60 CEOs, who represent organisations that make up nearly fifty percent of New Zealand’s emissions, have joined forces to tackle the issue of climate change. As the ambition, and desire for measurement, around these types of initiatives grows, so will the overlap with impact investment increase.

Policy drivers

Other opportunities for impact investment will be created as governments around the world undertake public sector reform, especially in relation to how social services are commissioned and contracted. An example of this is the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia, where bulk funding of human service providers is now being devolved directly to services users, who will have the choice to purchase services for themselves, based on their individual needs, through a competitive marketplace. Another example of commissioning reform is the movement toward outcomes-based funding, or ‘payments for results’, as previously discussed.

These shifts in policy are creating whole new markets, which will require existing providers to adopt different operating models while also attracting new market entrants and alternative financing options. The potential role of impact investment, and social enterprise, is particularly poignant here, and asks the question – what kind of organisations do we want delivering our essential services and care? Do we want businesses and investments being driven by the intention of maximising profits, or by maximising positive outcomes? The former may deliver good services, and the latter may be profitable, but the values and priorities of the two will be fundamentally different, leading to different outcomes over the long-term. In this respect, the proactive development of impact investment could have a major influence on the future culture of care and essential services.

Policies and regulation that relate to the environment are equally influential. And with global and national commitments on climate change likely to bite in the near future, significant market incentives, and sanctions, for positive and negative environmental impacts will be in the pipeline.

Citizen sentiment

All of these drivers are being reinforced by us – individuals, consumers, and citizens. Indeed, responsible investment is quickly becoming the new norm in Aotearoa New Zealand, as demonstrated by a recent Colmar Brunton survey (commissioned by the RIAA and Mindful Money), that found 72% of Kiwis expect their investments to be managed ethically, and 62% would shift their funds if they were managed in ways inconsistent with their values.

Much is made of the ‘millennial generation’ in influencing these trends but the numbers suggest a bigger shift in citizen sentiment. This is better understood as a millennial issue, a growing consensus on the need for change: “It has become accepted wisdom that millennials are driving the uptake of responsible investment. However, this survey shows that, while the commitment of those under 30 years is high, those over 60 years are equally as committed to invest responsibly, and they have far higher investment assets.”

Why the new jargon?

Through this discussion, we know that impact investment isn’t new, and we know that people are doing it in different ways, with different motivations, without necessarily needing to employ a whole new set of jargon. So, do we really need a new language in order to have more impact with our money?

While the jargon can grate, naming the practice and the sector is valuable in a number of ways:

Rigour – by being explicit about the practice we introduce specificity and accountability around measurement, and this is important as it relates to credibility and material change.

Potential for coherence and scale – being explicit provides the means to efficiently match the supply and demand side of the market, to design enabling policies, and develop specialised funds, intermediaries, instruments, and products. Impact can be created on an adhoc basis but genuine scale and transformation will require an organising force. This also relates to keeping up with global trends and developments. Around the world, impact investing is now a firmly established way of thinking about the future of finance, and it behooves us to be in sync.

A counterpoint to the status quo – we need to do things differently in order to change the trajectory and consequences of the current economic model. To do things differently, and to create a new normal, we have to be conscious of the changes that we’re making – what we’re doing and why. Having a new narrative, with specific strategies, practices, and guidelines, enables transition.

Key points

- The establishment of global frameworks such as the SDGs and The Paris Agreement on Climate Change are driving demand for new finance, and specifically SRI and impact investment. However, there is still a major financing gap (of more than US$2tn a year) between what is in play and what is needed.

- Domestically, the NPS is sitting on significant capital (maybe $20bn) that is aligned with mission-led activities and could be activated for impact investment.

- The Aotearoa New Zealand business sector is aligning with impact through the rise of social enterprise, the growth of tribal economies, and the increasingly progressive outlook of corporates and mainstream business – not least because evidence is indicating that responsible business behaviour results in better performance.

- Public sector reform, particularly in the area of service commissioning, will drive new demand for impact investment.

- Citizen sentiment is increasingly requiring institutional investors to consider non-financial returns in their decision-making, again bringing impact investment into play.

- Having specific language and terminology around ‘impact investment’ is necessary as it drives rigour, safeguards against bad actors, and enables strategies for scale.

The State of Play in Aotearoa New Zealand

In September 2017, the Ākina Foundation, promoted in association with JBWere and EY, released ‘Growing Impact Investment in New Zealand’. The report outlined the scale, breadth and momentum of impact investing globally, and how the field was developing domestically. It estimated that the Aotearoa New Zealand market could grow to NZ$5bn within a decade.

A year on, there have been a number of developments that are shaping the domestic market for growth, even if investment activity itself remains at a relatively low level. In this section we provide a scan of some of the key developments, and adjacent opportunities, to provide a sense of what’s going on from a holistic point of view.

Market infrastructure

The Impact Investing Network

In late 2017, the Impact Investing Network (IIN) was established to support the emerging community of practice around impact investment. The IIN now has over 250 members and has run a number of events. Through the IIN, in consultation with its members, the terms of reference for a National Advisory Board on Impact Investment were developed in early 2018.

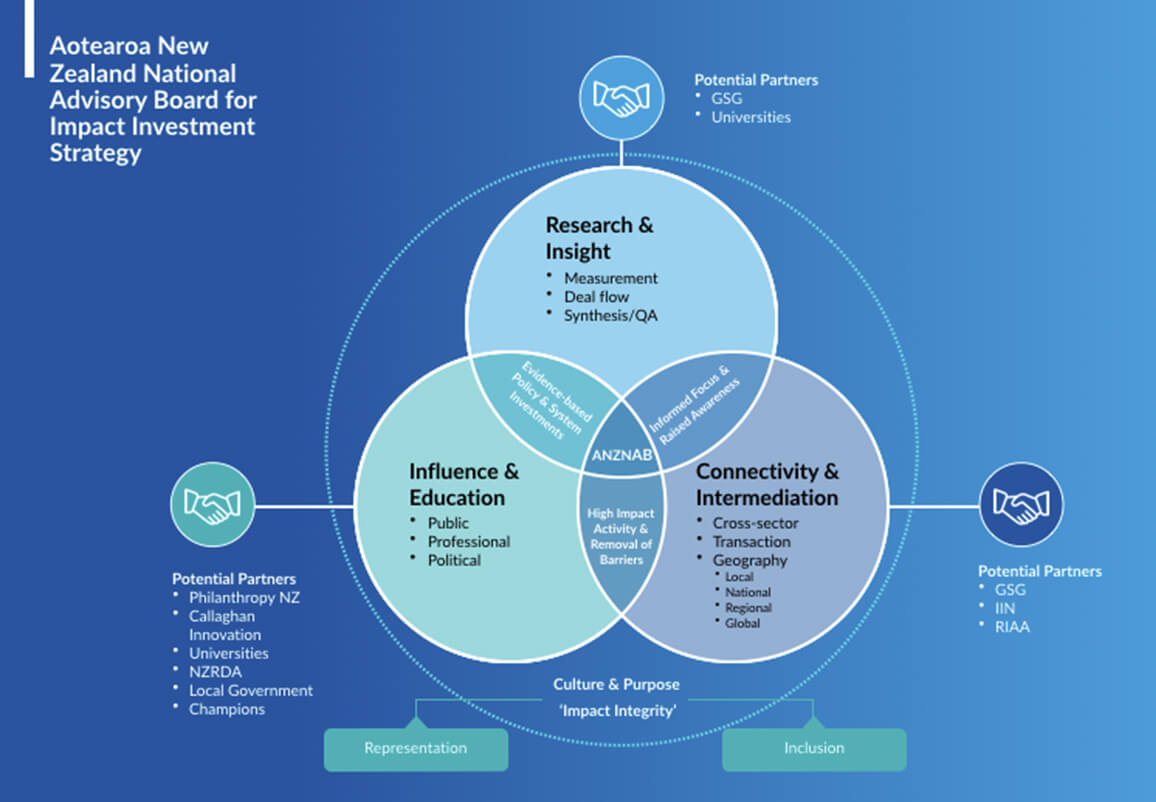

The Impact Investing National Advisory Board Aotearoa New Zealand

The Impact Investing National Advisory Board Aotearoa New Zealand (IINABANZ) was constituted in early 2018. The purpose of the IINABANZ is to connect New Zealand to global markets, learn from international experience, and develop the domestic market to support impact investment opportunities. The IINABANZ applied to become a formal member of the Global Steering Group for Impact Investing (GSGII) in August, and was formally accepted in October. It is now setting strategy and seeking funding for operations.

The Aotearoa Circle

In October 2018, the Aotearoa Circle was established – a voluntary initiative bringing together leaders from the public and private sectors to investigate the state of the country’s natural resources, and to commit to priority actions that will halt and reverse their decline. A key objective of the initiative will be to drive finance towards investments that align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. This work will be fostered by a finance forum chaired by New Zealand Super Fund Chief Executive, Matt Whineray, and Westpac Commercial, Corporate and Institution Manager, Karen Silk.

Mindful Money

In 2018, Mindful Money was established by former Oxfam CEO and Green Party MP Barry Coates, to scale up responsible investment and shift funding towards sustainability and low emissions. Mindful Money seeks to provide an independent and reliable source of information on responsible investment and related products in the market. Along with the RIAA, it is providing increased visibility and profile of responsible investment and related issues.

The Edmund Hillary Fellowship

The Edmund Hillary Fellowship (EHF) has also taken shape over the last year. The EHF may seem a less obvious contributor to market development but could be significant driver of immediate and catalytic impact investment activity. The EHF programme manages access to Aotearoa New Zealand’s Global Impact Visa – a three-year work visa for proven entrepreneurs with a focus on impact. Visa recipients become Fellows of the programme, and are mixed into cohorts with local social entrepreneurs. The EHF now has 108 Fellows, and will continue to grow.

The purpose of the programme is attract overseas talent who will build purpose-driven ventures, invest in high-impact projects, support the Kiwi startup community, and strengthen connection to global networks. It was EHF that supported Joel Solomon’s recent visit to New Zealand, a pioneering impact investor who is Chair of Renewal Funds, a mission-led venture capital firm based in Vancouver with CAN$98m in assets.

Many of the EHF Fellows are actively engaged in impact investing and facilitating investment into new ventures. Critically, these ventures are often based in Aotearoa New Zealand but accessing capital from overseas, where the impact markets are bigger and more mature.

Policy developments

The Green Investment Fund

The New Zealand Government launched the Green Investment Fund (GIF) as part of a wider suite of evolving policies on climate change, including the Zero Carbon Act. The GIF will receive a capital injection of NZ$100m from the Government, and will then operate independently. It aims to ‘crowd-in’ capital and ultimately leverage NZ$1bn of sustainability-focussed investments by 2020.

The Social Enterprise Development Programme

In late 2017, the New Zealand Government embarked on a four-year social enterprise sector development programme. This programme is managed through the Department of Internal Affairs and contracted to their strategic partner and intermediary, the Ākina Foundation. With a total investment of NZ$5.5m, the programme will cover five areas of work:

- Sector Engagement – the definition of the scope and needs of the sector, and the development of an engagement strategy which focuses particularly on youth and Māori

- Capability Development – continuous capability development throughout the life of the programme; establishment of support networks for social enterprises through regional hubs

- Finance – identification of capital barriers and requirements for growth

- Markets – establishment of easily accessed social procurement approaches and marketplaces

- Communications – promotion of the benefits of social enterprise to improve understanding of the sector’s role in the New Zealand economy.

The Productivity Commission

After a period of extensive engagement and analysis, the Productivity Commission released a report on the country’s pathways to shift to a ‘Low Emissions Economy’ that would achieve an ambition of net-zero emissions by 2050. The report indicated significant changes would be needed in respect to energy usage (particularly in vehicles), afforestation, and agricultural production. It recommended that Government establish a comprehensive and durable climate change policy framework, reform the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme and include some pricing to methane from agriculture and waste, and to allocate significant resources to innovation and technology. The latter two of these will drive opportunities for impact investment.

Callaghan Innovation

Callaghan Innovation, the Crown’s agency for innovation and commercialisation, is undertaking a strategy process to consider how it better supports social enterprises and businesses that deliver social and environmental outcomes, particularly through technology. This goal is made explicit in their new statement of intent (2018-2022).

Kiwisavers

Individual Kiwisaver providers have continued to respond to consumer demand, and shift managed assets into negatively screened funds. In 2018, the RIAA Benchmark Report stated that this shift constituted a significant part of the overall NZ$183.4bn now being managed as responsible investments, up from $131.3 billion in 2016 and $79 billion in 2015.

Supply of impact capital

Specialised funds

Ākina Foundation and New Ground Capital partnered to establish the ‘Impact Enterprise Fund’ (IEF). The fund will invest in businesses who have measurable impact and are incorporated in New Zealand. The fund seeks to make market-rate financial returns for investors and will focus on providing capital to high-growth ventures, so will only be appropriate for a select part of the demand-side market. The fund closed its first round in early 2018, with just over $8 million committed.

At the other end of the spectrum in terms of expected returns, SheEO launched a highly enabling investment offer to early-stage ventures run by women, selected through an open, competitive, and transparent process. The pool of capital was raised from around 500 ‘Activators’, each providing $1,000. Investments were made into five ventures, structured as unsecured and interest-free loans. The finance is complemented by mentoring from appropriate professionals from within the SheEO network. The programme has been a transformational boost for the selected ventures, but is small in size at this time.

Soul Capital, an early-stage social finance intermediary that pre-dates the IEF, continues operations. It seeks to provide first-mover finance alongside support services to New Zealand social enterprises. Soul Capital made an early investment into Conscious Consumers, who went on to raise more than NZ$2m for international expansion, at the end of 2017.

With backing from The Tindall Foundation and Kiwibank, Ākina also continued and expanded its Impact Investment Readiness programme. This programme provides a limited number of NZ$5,000-20,000 grants to social enterprises, and other mission-driven organisations, for business, financial, legal and other capacity building support from professional providers to support them in securing investment.

Community Trusts and Regional Funds

One of the most material developments on the supply side have been the growing commitments from various regional Community Trusts (e.g. Foundation North – Auckland and Northland, and Rātā Foundation – Canterbury, Nelson, Marlborough, and the Chatham Islands) to enter the market through more strategic and structured approaches. Foundation North has established a specialised innovation unit, which has impact investment as a key part of its remit. This is significant both because of their individual and collective, capacity (Foundation North has an endowment of around NZ$1.3bn) and their potential to invest at the concessionary end of the market (by bringing their grants funds into play alongside their corpus). This part of the market is currently underserved and offers high levels of demand and impact.

Māori assets

Iwi and Māori Trusts are increasingly becoming major players in the economy, particularly in land-based sectors. Their asset base continues to grow, currently estimated to total around NZ$50b, and there are more settlements to come. Given the cultural values that are embedded in these organisations, many have developed responsible investment strategies and are well poised to progress into Impact Investment.

Demand for impact capital

Potential size of the market

There is still little information on the scale of demand for impact investment. The ‘New Zealand Cause Report’ produced by JBWere indicates that the NFP sector has a collective income of around $20bn a year, mostly concentrated in about 10% of all NFP organisations. Overlapping, and in addition, we can estimate (by extrapolating data from comparable jurisdictions) the number of social enterprises in the sector to be around 2500, with a net growth rate of 7% per year.

In theory, NFPs with strong income streams and the majority of social enterprises could all be in the market for impact capital for a range of uses, including: innovation, growth, working capital requirements, and asset purchases.

In addition, there are any number of companies that would see themselves as being ‘purpose-led’, and in scope for impact investment. However, ways to identify these organisations are limited, outside of global certifications such as B Corps, which is only starting to get traction in New Zealand, and, more tenuously, membership to networks such as the Sustainable Business Network.

What do we know about the demand side?

In late 2017, the Social Investment Agency commissioned research to better understand the attitudes and requirements of organisations on the demand side of the impact investment market. The scope of the study included any organisation who operated to deliver social and/or environmental impact, and traded, to some degree, in a market-based environment. While this research was not formally published, its findings reported that:’

- 75% of respondents foresee, or are open to, employing impact investment in their future development plans. This was mostly driven by perceived, or experienced, barriers to innovation or growth.

- Social enterprises were most positive towards employing impact investment and often have operational models and capability sets that were more compatible.

- Respondents saw impact investment being used for a range of purposes, with the most predominant being growth, asset purchase, and, with increased financial stability or an enabling legal structure, innovation.

- Nearly all participants seeking impact investment have additional requirements to finance alone (i.e. technical support, governance, impact measurement) that make most existing sources of finance inappropriate and/or unattainable.

- The propositions of more explicit funds and products were strongly supported with the biggest need seen to be for ‘impact-first’ and / or ‘mixed motivation’ finance. A ‘finance first’ approach was seen as less relevant for the majority of participants due to the constraints associated with accessing market-rate capital, leaving organisations working in areas of market failure and with marginalised communities underserved.

In terms of demand from more commercial-minded companies, the Impact Enterprise Fund has received more than 170 applications since February 2018. While many of these have been ruled out for various reasons, they will continue to consider more than 100 companies that are potentially within the scope of the Fund.

Bigger plays

Beyond individual organisations, there has also been the emergence of a number of sophisticated initiatives that are seeking to unlock impact investment through large-scale, and often bespoke, mechanisms. Example of this include the Native Forestry Bond Scheme, New Ground Capitals housing funds, and the Waipā agri-impact fund (see case study).

These initiatives are ambitious and complicated to pull off, but the growing number of attempts suggests that more innovators are seeing opportunities to unlock impact capital as increasingly feasible. This is especially the case in sectors, or around issues, that are resistant to status quo approaches, such as the transition to sustainable land-use and social / affordable housing.

A distinctive flavour

While it is still early days, the market in Aotearoa New Zealand seems set to develop in ways that are very specific to our country context, with strong influences coming from the burgeoning social enterprise and purpose-led business sectors, the community trusts, and the tribal economies. Where these developments and interests intersect with Government priorities, we are likely to see opportunities for both impact investment activity and overall market development.

Key points

- There have been a number of significant developments in Aotearoa New Zealand in the last year that feed into the development of a domestic impact investment market. However, many of these developments do not explicitly reference impact investment and may create duplication / confusion if not aligned and connected with each other.

- While demand for impact investment is growing, there is still a disconnect with the (limited) supply of capital, and much more demand remains latent due to issues around capability, culture, and confidence.

- The development of the impact investment market in Aotearoa New Zealand is likely to have its own unique characteristics due to Māori culture, the structure of the philanthropic landscape, and current policy mix. This means that while there is still value in learning from other jurisdictions, we should be prepared to be proactive in the design and development of our own market infrastructure and institutions.

Leave a comment