– Photo Credit Tim Marshall

Access to forests for urban communities is vital for well-being, including cultural well-being in Indigenous peoples. There are often fewer forests, trees and green spaces in lower socio-economic communities. Our challenge is to ensure everyone in Aotearoa has an equal chance to access forests and connect with nature.

Human lives are often busy, nowhere more so than in cities, with little time to sit amongst Te Wao nui a Tāne-Māhuta (the great forest of Tāne-Māhuta) as older generations once did. Yet, this idea captures an important truth: that human health and well-being benefit from nature. The benefits of interacting with our natural world go far beyond simply viewing beauty. They address mental, physical and emotional health through increased physical activity, reduced stress, and opportunities to connect as we venture into the green spaces near our homes. Where trees and forests are woven into the fabric of cities, they reduce our exposure to pollutants, and provide us with access to a unique web of life where we can feel more connected to the planet.

Different types of nature, from community gardens to urban parks with wide open green spaces, contribute to our wellbeing. They encourage gardening, family biking, dog walking, and sports among other activities. However, in urban parks or green spaces there is generally sparse vegetation, with few trees or forested areas, limiting engagement with complex ecosystems and unmanaged nature. Here, we advocate for urban forests as a rich source of human well-being and connection to nature. We also challenge the inequities in access to urban forests across society. We highlight some of the challenges ahead in connecting all communities with urban forests.

– Tamariki and rākau

Value of forests in urban areas

Imagine walking into a forest down the road from where you live. What do you notice? What do you feel? You may notice flowering buds on the trunks of mahoe trees, or tall canopies of native tōtara stretched upwards. Perhaps a korimako alights on rātā flowers, looking for nectar. Forest spaces can often provide seasonal food resources, such as flowers and fruit that support many species from insects to birds. By providing these services, forest remnants can attract threatened species to cities. In Wellington, kākā have spread from Zealandia across the city, as have tūī as they seek the many remnant patches of forest that provide food for them.

Perhaps you notice that the wind has dropped, and the temperature is cooler in the leafy interior of even small areas of forest, more refreshing than the extreme heat outside. Kiekie may be stretched across the forest floor, up into the canopy, with tree wētā, beetles and other insects resting in the folds of their leaves. These forested remnants provide stable environments that support protected plant species. Even more importantly, these remnants provide safe havens for life that may not be able to relocate to habitats in other parts of the city. These forest patches also offer different ways for urban dwellers to increase their wellbeing. Moving through an urban forest provides opportunity to see pīwaiwaka flitting amongst the trees, or perhaps kids playing hide and seek behind the towering kahikatea trees that have stood for hundreds of years. You may also see whānau collecting plant leaves for rongoā making or cutting harakeke for weaving at the forest edge. Our actions and enjoyment reflect the diversity of age, worldview, and culture that we bring to our leisure activities.

For Indigenous peoples, nature is deeply embedded into ways of thinking about the world and is central to the creation and development of indigenous knowledge as well as the expression of cultural practices. The core of this relationship places Indigenous peoples as part of the interconnectedness of nature rather than separate from it, and embeds concepts of kinship, care and reciprocity into practices of harvesting and use. By valuing indigenous concepts, values and frameworks, relationships with urban nature can flourish in meaningful ways and support new ways to restore nature in urban places. Practices like weaving, food foraging, and medicinal plant harvesting in urban forests support cultural vitality and relationships with nature.

Understanding the various ways that we might connect to urban forest, and more broadly to nature, has been captured in Te Mana o te Taiao, the Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy. The Strategy encourages a holistic approach to biodiversity maintenance, restoration and protection in New Zealand. It highlights the importance of New Zealand’s biodiversity but also recognises the multiple bodies of knowledge and actions required to achieve positive outcomes for New Zealand’s biodiversity. The kinship perspective of indigenous communities to care for these areas encourages higher levels of connection and care for nature. This in turn contributes to pro-environmental behaviours. Recognising these benefits reduces the extinction of experience and the consequences that result from declining care for nature in general . Yet not everyone has the opportunity to benefit from the wellbeing opportunities forests bring to cities, because different levels of access and knowledge may cause difficulties for equitable engagement with forest.

Accessing urban forests

The urban forest is made up of forest patches, but also includes street trees, trees in parks and in backyards.

– Forest patches

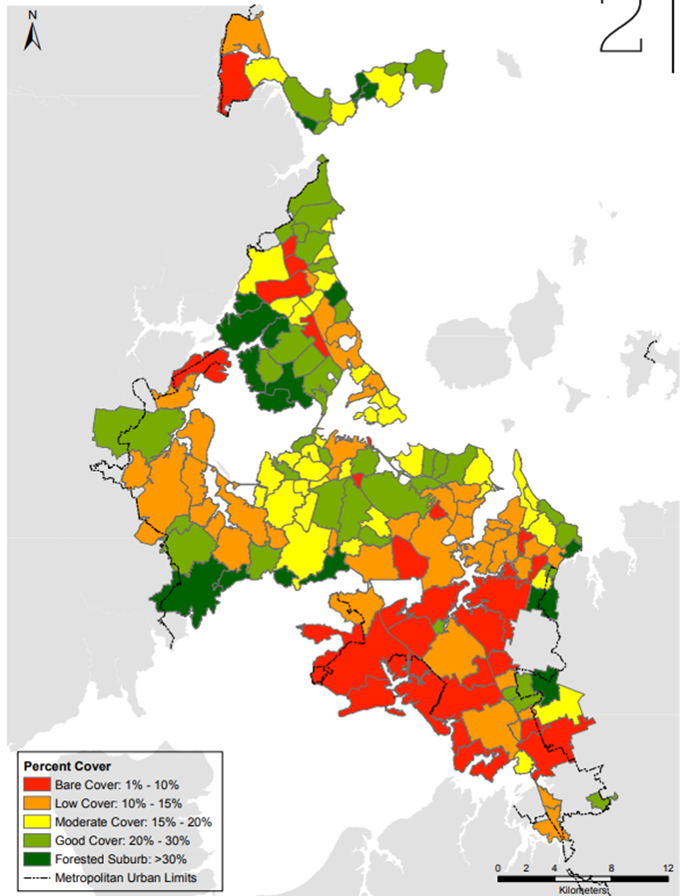

However, the physical and mental health benefits of engaging with urban forest may not be accessible to vulnerable low-income communities. Although urban nature can provide urban dwellers opportunities for social, physical and spiritual well-being, urban forests are often not evenly distributed across cities and may be absent from low socio-economic areas entirely. The Covid19 pandemic heightened the effects of this inequitable access experienced by communities, particularly for urban forest. In Melbourne city, more than 340,000 people had limited or no access to parklands within a 5-kilometre radius of their homes during lockdown, which was the distance restriction in place during that time. In Auckland, the Auckland Urban Ngāhere (AUN) strategy shows limited forest canopy cover in areas where social housing was built. Tree canopy cover in Auckland is unevenly distributed: the northern and western parts of the city have over 50 percent canopy cover where large forest areas are unsuitable for development, compared to low or minimal canopy cover in southern parts of Auckland like Māngere and Ōtāhuhu, where only 8 percent canopy cover exists.

– Auckland’s urban forest canopy cover by suburb, 2013. Credit Auckland Urban Ngahere Strateg

High tree density has a strong association with high property value locations.

For those living in low socio-economic areas of Auckland, there are fewer ways of improving mental health by connecting to nature in leafy spaces. The challenges in accessing urban forest and ensuring that appropriate species flourish in these spaces shows the need to not only increase access to these spaces, but to also ensure that the community’s needs, values and cultural connection are expressed in these areas. As well, some urban street and park trees are introduced species that may not be suitable for weaving or rongoā; the sheer number of such trees in our cities may frustrate Indigenous practitioners seeking to undertake cultural practices. Harvesting and gathering limitations dilute the strength of long-held relationships with indigenous plants and animals, and impact the longevity of cultural knowledge systems.

”Urban planning should prioritise the restoration of urban forest by integrating trees into development plans

Lack of access to nature is also experienced by young children. In low socio-economic locations where urban forest areas may be far away, children are less likely to engage in nature play, or to accompany their whānau to help with family harvesting activities. In addition, whānau may work long hours, there may be a lack of safe transport, or an overall waning interest in nature and biodiversity. These communities, who already experience disparities in accessing nature are now more disadvantaged in their access and engagement with urban forest. Increasing access to nature and to forest areas for all generations provides an opportunity to strengthen our level of care for nature.

– Whanau and rākau

How do we move forward and connect everyone?

The growing number of urban restoration groups highlights the desire to increase forested areas in the city. There is untapped potential to draw on many people’s knowledge of nature to support equitable access to forests. This will lead to increased appreciation of nature as well as increased human health and well-being. Urban planning should prioritise the restoration of urban forest by integrating trees into development plans and making existing spaces multifunctional for both people and biodiversity.

Examples of this integration can be seen worldwide in best practice planning. Both the Barcelona Green Infrastructure Biodiversity plan and the AUN strategy support increased forest and tree cover in urban areas, increased native planting in urban spaces, creation of ecological corridors, increased access to forest areas, and planning for the whole life-cycle of urban forest. As well as benefiting people, ecological corridors support the movement of wildlife such as native birds like kākā in cities, further enhancing opportunities for urban dwellers to see and support such taonga. Mārā hūpara (Māori playgrounds) in urban areas can encourage outdoor play in ways that tell the histories of a place, reinvigorating cultural knowledge. Mārā hūpara also support ecological corridors, local species and biodiversity in urban spaces. Weaving a range of worldviews and bodies of knowledge into planning, and in particular those of tangata whenua, will help to shift the value of urban forest from providing aesthetic needs to a focus on intrinsic and physical well-being, potentially increasing our affinity to nature and its protection into the future.

Leave a comment