The recent Vivid Economics report prepared for Globe-NZ covers different scenarios in which New Zealand can follow to achieve a low-emissions future. The excellent Net Zero in NZ report can be downloaded here. I’ll leave you to go through the report but the short story is New Zealand has to travel the “Resourceful or Innovative” track in order to decarbonise our economy in the second half of this century – no easy task. Amongst other solutions which I’ll discuss later – forestry, in particular growing trees for carbon sequestration plays a big part and represents some of the short term low hanging fruit available to us.

The signing in December 2015 of the Paris (Climate) Agreement and its subsequent ratification in very quick time thereafter in October 2016 was a very profound event but in reality doesn’t actually go far enough to reduce global emissions and only covers the period 2021 to 2030.

Carbon markets will form part of this agreement and we have seen a lot of changes in regards to these markets since 2009. At that time, New Zealand was the only federal Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) outside of Europe and now there are nineteen federal, regional and state-based schemes. China is about to commence a national ETS later this year. The ETS structure is now seen as the global model and New Zealand is seen as a leader in this area despite its small size.

Unlike the previous Kyoto Protocol (2008 to 2012) and its eight year extension (through to 2020), the Paris Agreement is a substantial global agreement that has already been ratified and will come into force in 2021. Until the USA signalled its intention to withdraw – it covered nearly 100% of global emissions covering a similar percentage of the planet. The recent decision by President Trump to withdraw from this agreement in four years’ time only reduces the emissions it covers by 15%. However, California – the 6th largest economy in the world remains committed via their own emissions trading scheme.

As our ETS enters its ninth year of operation and as New Zealand enters into its third climate target under the Paris Agreement, forestry is set to play a much bigger role in helping New Zealand meet its target of reducing emissions to 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Our ETS is a market-based tax, one of the few politically created financial markets that exist. Unlike normal financial markets, such as commodity or currency markets which have no end in mind and exist for price discovery and to manage the financial risks, carbon markets have an end in mind – the end of carbon and a price of zero.

Whilst a carbon tax is different to an ETS – they are different sides of the same coin. A tax is a fixed price on carbon emissions with an unknown reduction in emissions whereby an ETS is a floating market price and a known reduction in emissions through an emission CAP.

New Zealand has a bit of both in its current ETS – a hybrid. We have a floating price with a $25 price cap and no cap on actual emissions (intensity based). Whilst some of our settings may change in the future – it’s unlikely New Zealand will change its ETS to a carbon tax.

The New Zealand government recently announced its four-point plan after conducting a review of the scheme.

They have signalled the following intentions;

- Introduce auctioning

- Limit use of international units

- Replace the $25 Price Cap

- Decide on 5-year supply settings

They intend to take on further work around these proposals including consulting with the market and those affected by these decisions. Clearly, the government first wants to see the successful back-end of the election in September of this year. There are also other matters that need to be finalised around the establishment of international markets (Article 6) which is unlikely to occur before the end of next year.

Under the Paris Agreement – New Zealand has agreed to reduce emissions by around 235 million tonnes between 2021 and 2030. Given our electricity sector is highly renewable and half our emissions are agriculturally based – this will be a very difficult task because unlike many economies we don’t have a lot of low hanging fruit in which to decarbonise our economy.

This is where forestry will become an important choice but it’s only part of the solution as I’ll explain later.

As mentioned – our electricity sector is around eighty-five percent renewable, this figure continues to grow albeit slowly and we are expected to be at ninety percent by 2025 but from that point – it will become a very hard task to move to one hundred percent renewable electricity sources.

Agriculture is a tough one as well – whilst it reports emissions in the ETS, the agriculture sector is not responsible for paying for its emissions as that is picked up by the taxpayer. Part of the rationale for that is New Zealand has a high level of agriculture versus other developed nations at around fifty percent versus fifteen percent for developed economies. We are actually on par with developing nations who have a high level of agriculture relative to other economic activities.

It’s also an emission and economic argument – at present, there is no real fix for methane emissions and given agriculture is a big part of the human diet, it’s unlikely any methane inhibiting solutions will be put into animals either directly or through feed without thorough testing. New Zealand is spearheading research in this area and whilst early signs are promising, one would imagine any cure would involve years of testing before it’s considered safe. In addition, economically, our agricultural emissions are considered to be the least carbon intensive in the world so if our agricultural exports are hit with a carbon cost, it will make our goods more expensive and possibly cause carbon leakage whereby other economies less efficient than ours with a subsidised or nil cost on agricultural emissions become more attractive in terms of price. If that was to occur then both New Zealand and the planet loses as we only have one atmosphere and we simply export our wealth and cause greater emissions.

In other words – bringing agriculture in without a ready cure is simply a tax on farmers and on our economic competitiveness. Having said that – a change of government would most likely see agriculture phased in and in any event it has to come in eventually. So whilst it’s out of our ETS at present in terms of cost – get ready for at some point it will be brought in.

It ought to be pointed out that since our ETS has been going our emissions have not fallen, in fact they have risen and there has been little development on the abatement or sequestration front. Low carbon prices for many years didn’t help. Nevertheless – much of our economy has faced increased prices due to the ETS so why should agriculture continue to be excluded and shielded by the rest of us.

With substantial renewable electricity gains difficult, and agriculture off the table at present, there aren’t many easy choices in lowering our emissions. Electrification of our transport is one but that will take time and only goes part of the way in regard to lowering overall emissions.

So back to our Paris target and where we find 235 million tonnes of savings. This will come from three sources with domestic energy reductions being the smallest given the lack of real abatement opportunities. The largest will be using offshore units with demand expected to be close to 185 million tonnes however the international markets where these units will be sourced have not been developed yet. That leaves trees. The quick back of an envelope calculation suggests at best we can only grow 50 million tonnes through forestry between 2021 and 2030 and that is mainly due to competition for land use and the cost of land. Nevertheless, there are many compelling reasons for growing trees with the likely high carbon price being the main underlying reason. I’ll cover some of these later.

Forestry has been the main printing press of our carbon units in the ETS. The vast majority of carbon units (NZUs) come from forestry through sequestration in trees. Forest owners with trees planted after January 1st, 1990 (post-1989) can voluntarily enter the ETS and claim NZUs annually. These are issued by the government. They can on-sell these units to emitters caught up by the ETS who then annually hand these over to the government. The government then cancels these units. That’s how the ETS system works.

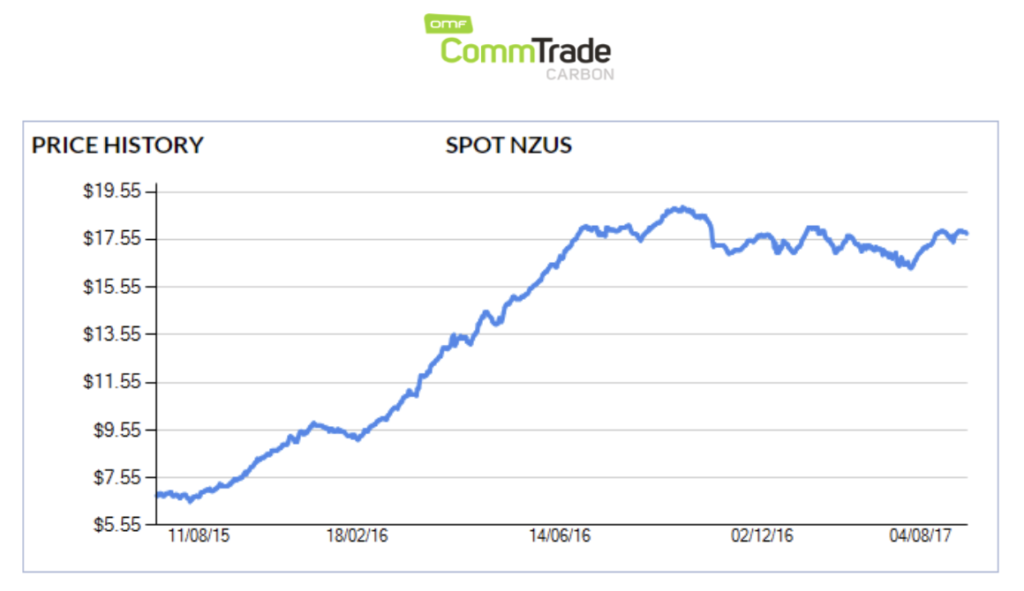

The price of carbon since our firm OMF transacted the first trade in the ETS in March 2009 has ranged from just over $20 per tonne/NZU to below $2 in 2012 back up to the current price at time of writing at $18 per tonne/NZU.

Daily Price – Spot NZUs – Source CommTrade

Our ETS has also seen some substantial changes in the eight year lifetime. Whilst New Zealand’s annual emissions are close to 80 million tonnes, when you exclude agriculture, it’s only 40 million tonnes. In addition, up until the end of 2016, the remaining 40 million tonnes was only subject to a fifty percent requirement – in other words, emitters were only responsible for 20 million tonnes. This “buy one – get one free” setting has started to be phased out starting this year (2017) and will be fully gone by 2019.

When the Paris Agreement comes into force in January 2021, the New Zealand economy will have 40 million annual tonnes of emissions excluding agriculture assuming we don’t have a government that phases in agriculture.

Therefore, when you look at the current price of carbon at $18 per tonne/NZU with forestry being the main provider of units, and the fact that ETS settings double between now and 2019 and New Zealand has to reduce emissions by 235 million tonne by 2030 – it’s hard to be bearish on the price of carbon in any way.

Also, when international markets develop – it’s quite easy to imagine carbon prices being significantly higher than where they are now. In March 2009 – the price of Certified Emission Reductions (CERs), an international carbon unit at the time was NZ$50 per tonne. Also, many other nations who have signed up to the Paris Accord will need access to international markets so do not expect these international units to be cheap. In addition, international markets for carbon will most likely link with countries who have an ETS including New Zealand and that will impact the price of NZUs. The fact is New Zealand cannot meet its Paris target unless it has access to international markets.

The government has signalled that access to international units will be restricted which is important. Whilst it still too early to say exactly how this will transpire given international markets for Paris don’t exist yet – our international demand against growing trees is likely to be close to “5 to1” therefore there will be a requirement for emitters to buy forestry NZUs for the balance.

Politically, the New Zealand ETS is here to stay. It was bought in by Labour in 2008 and amended by National in 2009. It’s a bi-partisan policy. The Greens threatened to replace it with a tax but we believe that is now extremely unlikely. Replacing the ETS after eight years into something else is very problematic. You will have the current ETS under National or a stronger one under Labour. Access to international markets would depend on an ETS.

Therefore – we see many reasons to grow trees. The ETS will incentivise people to do this with price being the main determinant. Whilst price ranges vary – many have stated that a carbon price between $15 and $20 per tonne/NZU will encourage people to plant trees for carbon whilst others in the sector have stated it needs to be above $25 per tonne/NZU given the current price of land and the required return on the risk.

There are other environmental and economic incentives brought about by an ETS and a healthy price on carbon. Other than the standard Pine forest which gives you logs and carbon, there are other species such as Manuka which give you honey, oil and carbon incomes as well.

The environmental benefits are many with the ability to halt land erosion being a main one. In some areas of New Zealand such as Gisborne, there are afforestation grants to assist in this activity.

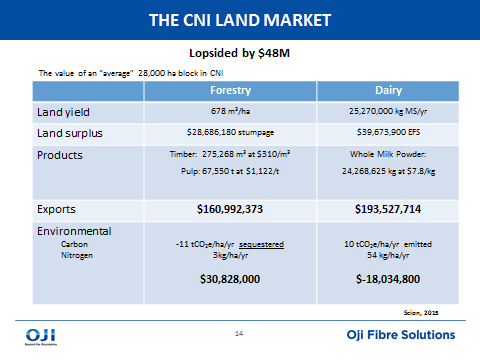

We see two opportunities for agriculture as well. One being the competitiveness of growing trees for carbon and fibre versus using the land for other agricultural uses. Scion, a New Zealand Crown Research Institute, did a paper in November 2015 on identifying complementarities for dairy and forestry in the central North Island. This showed that carbon even at much lower levels than the current price stands up financially. I have often joked with farmers that you don’t have to get up early to milk or move your trees around. We wouldn’t recommend dairy farmers grow trees on their best land but every farm has marginal land.

The other opportunity is growing carbon for emitters. Long term carbon offtake agreements for emitters are attractive. It helps reduce their risk by giving them options on a long term price of carbon. You can enter into agreements whereby emitters agree to buy your carbon every year over a five, ten or even fifteen year term. The price of the carbon could be fixed or split between fixed and floating.

Non-productive or marginal land now has a future under the ETS based on current carbon prices.

Another reason the agricultural sector should consider growing trees is risk mitigation. Eventually, agriculture will come into the ETS. Let’s not forget the political risk – we have two elections before the Paris agreement starts in 2021 and if Labour wins one of those, it has already signalled it will bring in agriculture as well as strengthening the ETS overall. Therefore, farmers should look to either grow trees for mitigating this risk. Whilst it’s likely the point of obligation for agriculture will be the processor level and not the farm level – that may not be the case. Farmers could have the option of opting in. In any event – there will be demand from the agriculture sector for carbon and you might as well be one of the sources for it. It will help reduce your own emission costs independent of the other benefits.

Leave a comment